How

the US Fails Its Most Important Fish Habitats

|

| Photo by Will Collette |

This argument is simple, eye-catching and undeniably true from a

scientific perspective: if we want healthy populations of fish, crabs and

shrimp, we need to protect key habitat where they live, breed and feed.

But do we?

The answer to that question, according to new report from the Center for American Progress, is a

resounding no.

Not only that, things have gotten worse for fish habitats — and

consequently, fisheries — since the Trump administration took office. And that

puts fish populations, ecosystems, and part of the human food system at risk.

The heart of the problem, according to the report, lies the way

we manage what’s known under U.S. law as an EFH, or “essential fish habitat.” These EFHs represent 800 million

acres of habitat, including breeding and feeding sites for nearly 1,000

federally managed species, covering everything from coral reefs to rivers and

wetlands.

Under the EFH regulatory structure, the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration works with U.S. fisheries

management councils — groups that consist of government managers and

representatives from industry, academia and the environmental community — to

identify and map these habitats.

The law also gives fisheries councils virtually all the power

and responsibility to protect these critical habitats and the sensitive species

that live in them from manmade threats, including destructive fishing gear.

Unfortunately, according to the new report, councils are

largely not using their power to protect. Despite their

designation as “essential,” most of these habitats have no additional

protections at all — they’re not managed differently than any other kind of

marine or river habitats. Much of the rest isn’t protected strongly enough,

according to the Center’s examination.

Map of essential fish habitats overlaid with those that have

protections in place. Source: NOAA

Ocean policy analyst Alexandra Carter, the report’s lead author, tells me they set out to understand the scope of the problem, but did not expect what they found.

“We were floored at how much identified EFH there is, but how

little actual protections result from it,” she says.

In fact, the report concludes with an alarming warning, “The

vast majority of U.S. waters have insufficient protections for ensuring a

healthy future for American fisheries and oceans.”

The Weakest Link

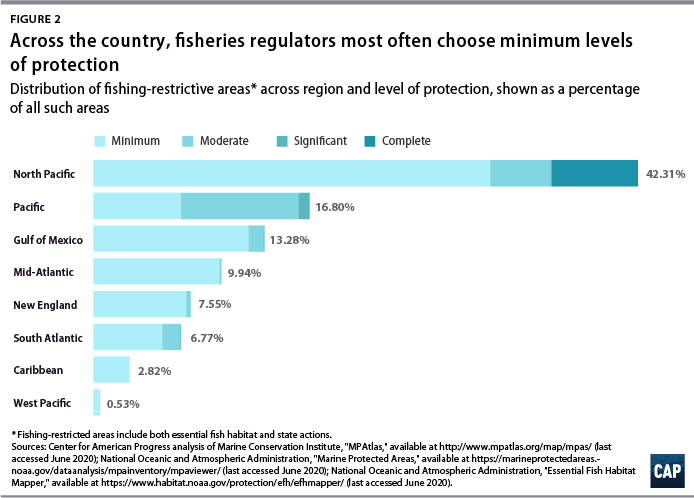

Of the few areas that had protections, three-quarters had what

the authors call “minimal protections” — usually just minor modifications to

fishing gear that don’t accomplish much conclusive good.

One example of such a minor gear modification can be found in the Gulf of Mexico, where bottom-trawl nets dragged across the seafloor feature a heavy chain called a “tickler,” which improves catches by stirring up bottom-dwelling species like crabs, but which can also do a lot of damage to the habitat.

In order to minimize the risk of damage, the EFH protection established by the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council requires the tickler chain to have one link weaker than all the others. This supposedly enables the chain to break, if necessary, rather than continue to damage habitat.

This sounds good in principle, but according to Carter, “There’s

no rule about how weak the link is supposed to be. It just has

to be weaker than the other links.”

In many cases, the requirements to protect identified these key

habitats consist entirely of things that fishermen were already doing, such as

gear modifications put in place because they improve fishing, not because they

protect the habitat

“That means there’s little additional protection, if any at

all,” Carter says. “A list of new rules that consists of things people were

already doing is not really what we think of when we think of a new protected

area.”

How can this be? Well, according to Gib Brogan, an Oceana senior

campaign manager who wasn’t involved in this report, the process of identifying

what counts as EFH is a scientific one with clear guidelines, but what’s

supposed to be done to protect an EFH once it’s identified is a lot more

flexible.

“There’s been a lot of latitude given to the fisheries

management councils,” he says. “Fishery managers have to make rules to minimize

the adverse effects of fishing, but there’s lots of discretion about what

exactly that means. And it’d be tough to make the case that the councils are

fully implementing and fully achieving the requirements of the law. Habitat

protection is often treated as a nuisance by managers, addressed not because

it’s a priority but because the courts say they have to after they’re sued.”

A Worsening Problem

While this is a longstanding problem, it, like many other

environmental issues, has gotten worse during the Trump administration.

“Science-based management is the key to modern fisheries, and

the current administration doesn’t value science particularly highly,” Brogan

says.

The regulations and processes for identifying EFH haven’t

changed, but Carter notes that there’s been a noticeable change in attitude

among the councils as a result of the Trump administration’s anti-regulation

agenda.

It was pressure from the New England fisheries management council, for example, that resulted in recent news that an Atlantic marine protected area would lose its protections. And a recent Executive Order solicited recommendations from councils for ways the administration could reduce regulatory burdens on fisheries.

It was pressure from the New England fisheries management council, for example, that resulted in recent news that an Atlantic marine protected area would lose its protections. And a recent Executive Order solicited recommendations from councils for ways the administration could reduce regulatory burdens on fisheries.

Source: Center for American Progress

There have also been other, non-EFH related cases where the administration ignored science when getting involved in fisheries management, including issues related to recreational fisheries management and issues related to marine zoning.

“If we just let the councils ask the president to allow fishing

in all our MPAs and not have any protections in essential fish habitats, we’re

just not doing the best we can for our ocean ecosystems,” Carter says. “The

councils are poised to take advantage of any opportunities to allow more

fishing. It’s my opinion that with the Trump administration these opportunities

seem to be much more abundant than in previous administrations.”

Of course, most of the protected EFH areas aren’t what

scientists typically talk about when discussing marine protected areas,

especially in the context of a goal to strongly protect 30% of the ocean by

2030. But experts say establishing stronger protections in EFHs would

contribute to the same goals.

The report also cites the administration’s trade policies and the continuing threat of climate change as elements that have worsened EFH protection over the past three and a half years.

Can We Solve This Problem?

The report includes two key suggestions for improving the way we

use EFH regulations to protect the oceans.

The biggest is to introduce a new requirement that any

identified essential fish habitat have at least some substantive protections,

usually in the form of restricting what kind of destructive fishing practices

can or can’t take place there. Just noting that a place is important and should

be protected without giving it any kind of actual protection, the authors say,

is not especially useful.

And while there’s value in allowing the councils broad latitude to make solutions that work for local conditions, the fact that so much EFH remains unprotected or minimally protected is cause for concern and a reason for reform.

And while there’s value in allowing the councils broad latitude to make solutions that work for local conditions, the fact that so much EFH remains unprotected or minimally protected is cause for concern and a reason for reform.

The report also suggests ways to improve the public consultation

process for designating and protecting essential fisheries habitats. This is

often used for other environmental regulations under U.S. law and has allowed

for a more transparent and effective process.

“We should have EFH, but we should improve it so it’s

meaningful,” Carter says. “If we’re not doing what we can to preserve the

valuable resources we have in the ocean, we are failing the future fishing

industry of America. Protecting the ocean is a promise to the future to maintain

public resources for the benefit of everyone.”

David

Shiffman is a marine biologist specializing in the ecology and conservation

of sharks. He received his Ph.D. in environmental science and policy from the

University of Miami. Follow him on Twitter, where he's always happy to answer

any questions anyone has about sharks. http://twitter.com/whysharksmatter