J. Alexander Navarro, University of Michigan

Health officials have warned that the U.S. must act quickly to halt the spread – or we risk losing control over the pandemic.

There’s a clear consensus that Americans should wear masks in public and continue to practice proper social distancing.

While a majority of Americans support wearing masks, widespread and consistent compliance has proven difficult to maintain in communities across the country.

Demonstrators gathered outside city halls in Scottsdale, Arizona; Austin, Texas; and other cities to protest local mask mandates. Several Washington state and North Carolina sheriffs have announced they will not enforce their state’s mask order.

I’ve researched the history of the 1918 pandemic extensively.

At that time, with no effective vaccine or drug therapies, communities across the country instituted a host of public health measures to slow the spread of a deadly influenza epidemic: They closed schools and businesses, banned public gatherings and isolated and quarantined those who were infected.

|

| Officials wearing gauze masks inspect Chicago street cleaners for the flu, 1918. Bettman/Getty Images |

In mid-October of 1918, amidst a raging epidemic in the Northeast and rapidly growing outbreaks nationwide, the United States Public Health Service circulated leaflets recommending that all citizens wear a mask.

The Red Cross took out newspaper ads encouraging their use and offered instructions on how to construct masks at home using gauze and cotton string.

Some state health departments launched their own initiatives, most notably California, Utah and Washington.

Nationwide, posters presented mask-wearing as a civic duty – social responsibility had been embedded into the social fabric by a massive wartime federal propaganda campaign launched in early 1917 when the U.S. entered the Great War.

|

| Policemen in Seattle, Washington, wearing masks made by the Red Cross, during the influenza pandemic, December 1918. National Archives |

In nearby Oakland, Mayor John Davie stated that “it is sensible and patriotic, no matter what our personal beliefs may be, to safeguard our fellow citizens by joining in this practice” of wearing a mask.

Health officials understood that radically changing public behavior was a difficult undertaking, especially since many found masks uncomfortable to wear.

Appeals to patriotism could go only so far. As one Sacramento official noted, people “must be forced to do the things that are for their best interests.”

The Red Cross bluntly stated that “the man or woman or child who will not wear a mask now is a dangerous slacker.” Numerous communities, particularly across the West, imposed mandatory ordinances. Some sentenced scofflaws to short jail terms, and fines ranged from US$5 to $200.

|

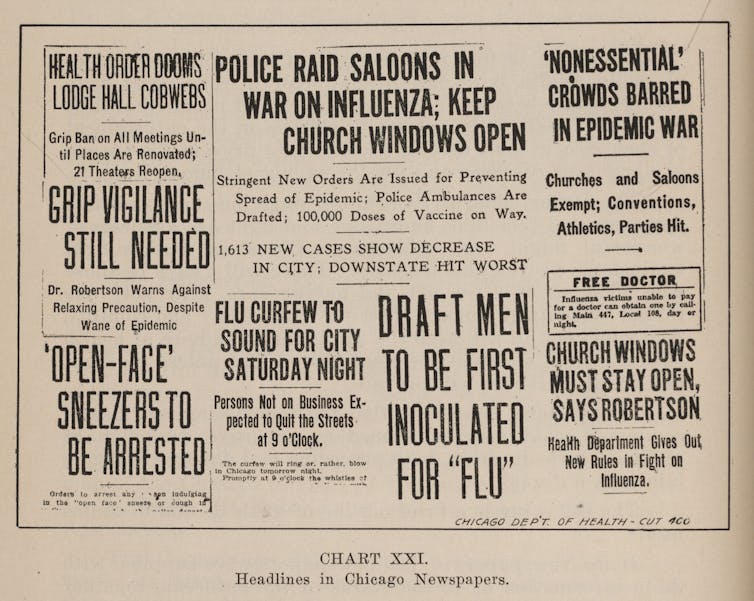

| Collage of newspaper headlines related to the previous year’s influenza pandemic, Chicago, Illinois, 1919. Headlines include ‘Police Raid Saloons in War on Influenza,’ ‘Flu Curfew to Sound for City Saturday Night’ and ‘Open-Face Sneezers to Be Arrested.’ Chicago History Museum/Getty Images |

For example, it took several attempts for Sacramento’s health officer to convince city officials to enact the order.

In Los Angeles, it was scuttled. A draft resolution in Portland, Oregon led to heated city council debate, with one official declaring the measure “autocratic and unconstitutional,” adding that “under no circumstances will I be muzzled like a hydrophobic dog.” It was voted down.

Utah’s board of health considered issuing a mandatory statewide mask order but decided against it, arguing that citizens would take false security in the effectiveness of masks and relax their vigilance.

As the epidemic resurged, Oakland tabled its debate over a second mask order after the mayor angrily recounted his arrest in Sacramento for not wearing a mask. A prominent physician in attendance commented that “if a cave man should appear…he would think the masked citizens all lunatics.”

In places where mask orders were successfully implemented, noncompliance and outright defiance quickly became a problem. Many businesses, unwilling to turn away shoppers, wouldn’t bar unmasked customers from their stores.

Workers complained that masks were too uncomfortable to wear all day. One Denver salesperson refused because she said her “nose went to sleep” every time she put one on. Another said she believed that “an authority higher than the Denver Department of Health was looking after her well-being.”

|

| Precautions taken during the 1918 flu pandemic would not allow anyone to ride street cars without a mask. Here, a conductor bars an unmasked passenger from boarding. Universal History Archive/Getty Images |

In Seattle, streetcar conductors refused to turn away unmasked passengers. Noncompliance was so widespread in Oakland that officials deputized 300 War Service civilian volunteers to secure the names and addresses of violators so they could be charged.

When a mask order went into effect in Sacramento, the police chief instructed officers to “Go out on the streets, and whenever you see a man without a mask, bring him in or send for the wagon.” Within 20 minutes, police stations were flooded with offenders.

In San Francisco, there were so many arrests that the police chief warned city officials he was running out of jail cells. Judges and officers were forced to work late nights and weekends to clear the backlog of cases.

Many who were caught without masks thought they might get away with running an errand or commuting to work without being nabbed. In San Francisco, however, initial noncompliance turned to large-scale defiance when the city enacted a second mask ordinance in January 1919 as the epidemic spiked anew.

Many decried what they viewed as an unconstitutional infringement of their civil liberties. On January 25, 1919, approximately 2,000 members of the “Anti-Mask League” packed the city’s old Dreamland Rink for a rally denouncing the mask ordinance and proposing ways to defeat it. Attendees included several prominent physicians and a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

|

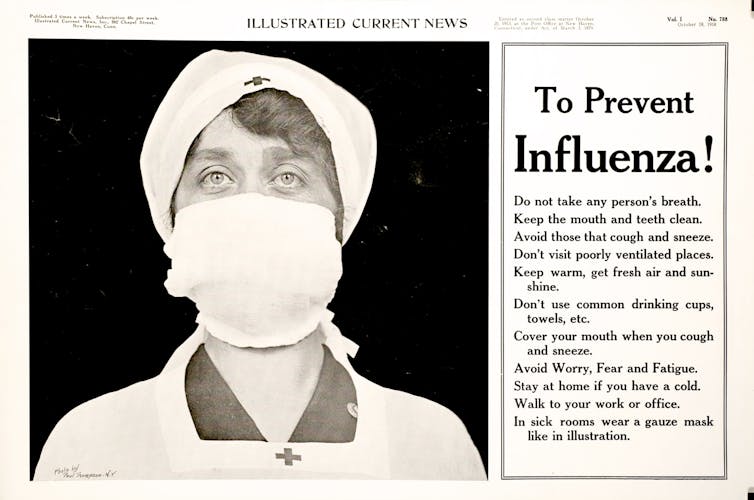

Poster of a Red Cross nurse wearing a gauze mask over her nose and mouth

– with tips to prevent the influenza pandemic.

|

It is difficult to ascertain the effectiveness of the masks used in 1918. Today, we have a growing body of evidence that well-constructed cloth face coverings are an effective tool in slowing the spread of COVID-19.

It remains to be seen, however, whether Americans will maintain the widespread use of face masks as our current pandemic continues to unfold.

Deeply entrenched ideals of individual freedom, the lack of cohesive messaging and leadership on mask wearing, and pervasive misinformation have proven to be major hindrances thus far, precisely when the crisis demands consensus and widespread compliance.

This was certainly the case in many communities during the fall of 1918. That pandemic ultimately killed about 675,000 people in the U.S. Hopefully, history is not in the process of repeating itself today.

This article was updated to correct the location of sheriffs mentioned.

J. Alexander Navarro, Assistant Director, Center for the History of Medicine, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.