James M. Honeycutt, University of Texas at Dallas

|

| Who will wait on the checkout line footprints and who will rage against them? Al Seib/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images |

Some people dutifully endure the hardships of coronavirus lockdown, while others can’t be bothered to keep their distance. Why?

As a cognitive researcher, I’m interested in how what psychologists call the “Big Five” personality traits influence the ways individuals deal with social distancing rules in daily life. Who is more likely to mask up every time they leave their home? And who is more likely to flout these evolving behavioral expectations?

Personal space, territorial invasion

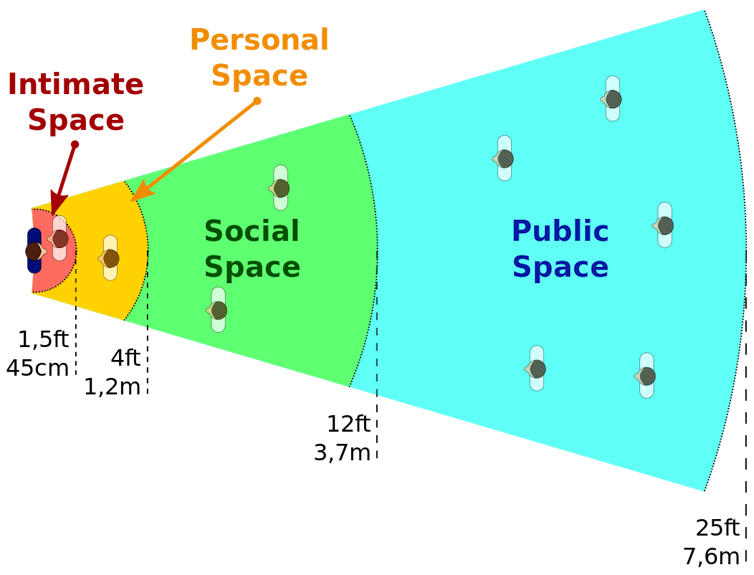

How comfortable you are being near to other people has a big cultural component. Anthropologist Edward T. Hall made a study of what he called proxemics, measuring personal space expectations around the world.

Pandemic response means the personal space bubble is now bigger than the previous norm. Jean-Louis Grall/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Pandemic response means the personal space bubble is now bigger than the previous norm. Jean-Louis Grall/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SAWhen people violate proximity norms, it can feel like they’re invading your territory. And nowadays, the stakes are higher than just your personal comfort – these distance guidelines are meant to protect you from infectious germs.

Subconsciously, everyone knows the traditional spatial zones. The “wait here” foot emblems now found at a store’s checkout line are necessary to help rewrite the cognitive script for where you stand until it becomes a mindless habit. You are forced to “unlearn” subconscious behavior; old dogs must learn new tricks.

Strangers who invade your social distance are being aggressive if they’re aware of what they’re doing. But if it’s done mindlessly or subconsciously, then personality traits are helping drive the behavior.

Predictions based on personality traits

For more than four decades, psychology researchers have divvied people up by personality types based on an individual’s combination of five key traits. They’re used to predict how people make purchases, behave at work, even long-term life outcomes like marriage stability and career achievement. Paul Costa and Robert McRae popularized the acronym OCEAN, for openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

|

| Everyone varies from high to low on each of the five personality traits. Olivier Le Moal/iStock via Getty Images Plus |

Openness reflects a tendency to think in abstract, complex ways. People high in openness tend to be adventurous and intellectual and enjoy the arts, while those on the opposite end of the spectrum tend to be practical, conventional and focused on the concrete.

The more open your personality is, the better you might cope with uncertainty over a long, sustained period – as in the case of a global pandemic.

Conscientiousness is the tendency to be habitually careful, reliable, hard-working, well-organized and purposeful. A conscientious person controls, regulates and directs their impulses. They would likely be early adopters of mask-wearing, even without direction to do so. This trait makes someone less willing to violate territorial space and social distancing guidelines.

Extroversion is characterized by being outgoing and drawing energy from interacting with others, compared to introverts who get their energy from within themselves. Behavioral neuroscience research has revealed two subtypes of this trait.

Agentic extroversion is about being comfortable in the limelight and taking a leadership position. These people are less likely to feel a strong bond with others and have more interest in going for rewards in social or workplace contexts.

On the other hand, affiliative extroverts don’t seek out leadership roles as much and have close social bonds with a lot of people from which they gather happiness and meaning.

Both types of extroverts would likely enjoy virtual networking during isolation, while probably struggling with isolation if sheltering alone.

Agreeableness reflects compliance. It is the opposite pole of antagonism and reflects a tendency to be good-natured, acquiescent, courteous, helpful and trusting. People high in this trait would probably go along with mask-wearing right away and be more likely to follow social distancing guidelines as soon as they’re announced without grumbling about the rules.

Neuroticism is characterized by impulsivity and a tendency to experience negative emotions including anxiety, worry, fear, anger, depression or sadness, hostility, self-consciousness and loneliness.

This trait is associated with wishful thinking and disengagement in order to escape feelings of distress. Presumably people high on neuroticism would tend to react to the pandemic with avoidance and denial.

The dark triad of personality traits

Personalities can have their dark sides, too.

Narcissism involves loving oneself obsessively; it goes along with grandiosity and vanity.

Machiavellianism is about manipulating others; it’s characterized by cynicism and long-term, calculating strategies.

Finally there’s psychopathy, meaning a lack of empathy. Psychopathic people are usually impulsive and have cold interpersonal relations. Individuals at the higher end of the continuum are deceptive, aggressive, sexually promiscuous and coercive.

All of these dark triad traits, as psychologists group them, would likely be associated with more social distancing violations.

Personality influences your behavior

|

| Personality traits influence who’s fine with masks and who isn’t. andresr/E+ via Getty Images |

Pulling from meta-analyses of how personality affects pro-social behaviors, I’ve come up with this formulation. I have in mind coronavirus-mitigating behaviors in the U.S., but it could be tested cross-culturally and in other contexts.

Social distancing violator = Low openness + Low conscientiousness + Low agreeableness + High neuroticism + High Machiavellianism + High narcissism + High psychopathy + Error

My model predicts that a person who scores lower in openness, conscientiousness and agreeableness would be more likely to violate social distancing guidelines. Same for someone higher in neuroticism, Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy.

The error term in the equation is a bit of a fudge factor; it represents all the variation in social distancing that is not explained by the personality traits. For example, political ideology influences social distancing compliance, with Republicans less likely to adhere to social distancing orders.

Psychology researchers are starting to collect data during the pandemic that supports this model. In one study, for instance, Pavel Blagov found that people with lower levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness were less likely to endorse health recommendations related to social distancing and hygiene during the coronavirus pandemic.

Personality is not fixed; it can evolve over one’s lifespan. As the coronavirus crisis drags on, I’ll be interested to see how adherence to social distancing guidelines changes over time – and wondering how much personality traits are changing too.

James M. Honeycutt, Professor Emeritus of Communication Studies at Louisiana State University; Lecturer in Executive Education, University of Texas at Dallas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.