Daniel Mandell, Truman State University

|

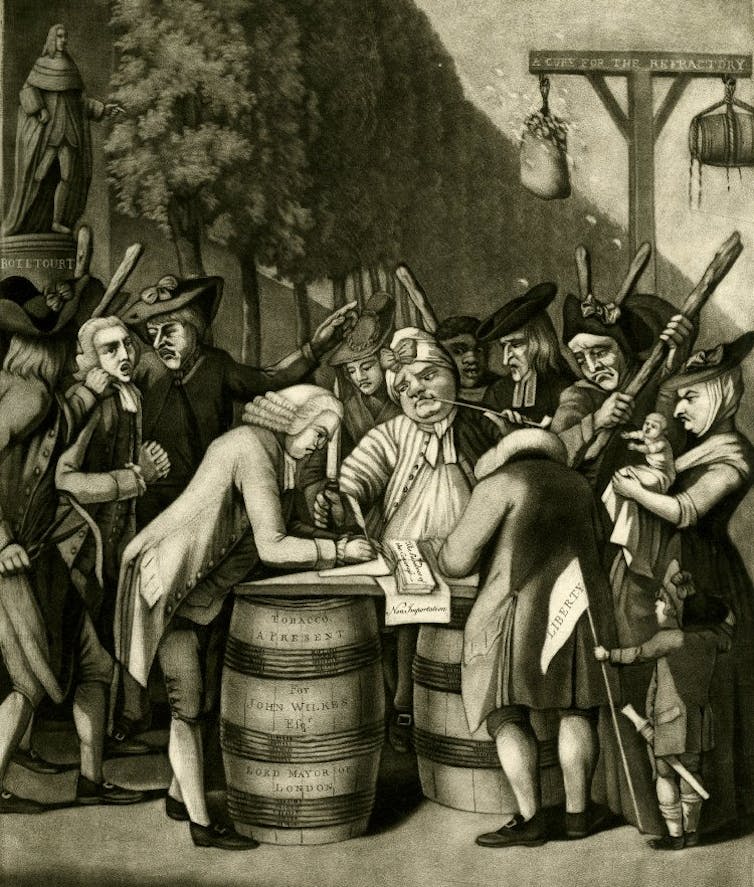

| In a 1775 cartoon, a British cartoonist mocks how wealthy elites were compelled by ordinary Americans to respect trade and price regulations. Philip Dawe/Wikimedia Commons |

For the origins of these concerns, commentators usually point to the Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century, when a few men gained immense wealth and power in the U.S. and workers suffered extreme poverty.

But fears of great wealth and the need for economic equality go back to the country’s origins.

Wealth as a danger to the nation

By the 1700s, Anglo-Americans generally believed that the best government was a republic that would ensure the public good by avoiding concentrated wealth.

The British political tradition limited voting to men who owned property; about 20% in England, but 50% to 80% in their American colonies.

In 1773, as the colonies drew closer to revolt, New Haven minister Benjamin Trumbull urged elected officials to keep property “equally divided,” to not allow “a few persons to amass all the riches and wealth of a country.”

Four months after the Declaration of Independence, the Pennsylvania Packet newspaper reported a proposal for the state’s legislature to tax wealth, “lessening property when it becomes excessive in individuals.”

During the war for independence, there were widespread state and local efforts to regulate prices of goods and services. The rules drew on this new egalitarian ideal and medieval assumptions that a community could set prices for necessities.

Early equality

|

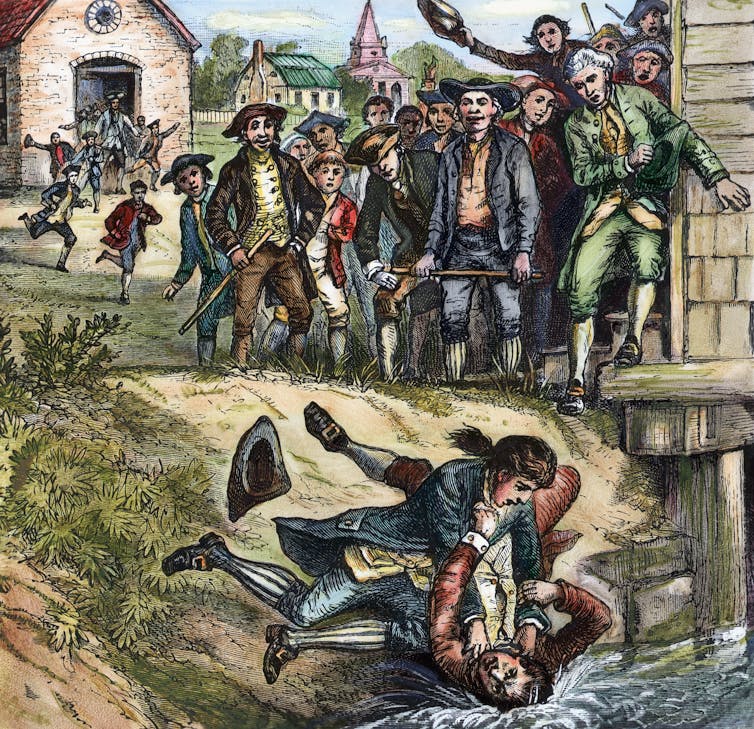

| A rebel and a government supporter brawl over tax burdens during Shay’s Rebellion. Bettman/Getty Images |

Famed lexicographer Noah Webster, in his 1787 pamphlet supporting the proposed U.S. Constitution, voiced the widespread view that the American republic relied on the “general and tolerably equal distribution of landed property.”

But many American leaders and writers feared the future. States had issued promissory notes to raise money. Wealthy merchants had bought them up at deep discounts – and now demanded full repayment.

Efforts to pay them by imposing ruinously high property taxes drove revolts in western New England and eastern Pennsylvania that were barely contained. Chaos and conflict threatened.

Facing the threat of wealth

Americans proposed various solutions to the threat of corrupting wealth and power. In 1785, Thomas Jefferson proposed progressive estate taxes.

In 1797, famed Revolutionary writer Thomas Paine recommended an estate tax to fund annual old-age pensions and a small payment to every person at age 21. More common were calls to limit land holdings. These proposals failed, however, largely because Americans disliked taxes and strong governments.

But the new nation did make one noticeable effort for a more equal future: States abolished entail and primogeniture. These English legal traditions had served to concentrate wealth and power across generations by preventing the sale or alteration of part of an estate (entail) and passing all of it to the eldest son (primogeniture).

By the end of the 18th century, nearly every state barred entail and required the equal division of estates whose owners died without a will. Research has found that, at least in Virginia, those reforms did reduce the size of inherited farms. However, this focus on land overlooked the growing role of capital in the nation’s economy. Accumulation would be increasingly measured in dollars rather than acres.

Class conflict rises

During the early 19th century, slavery-dependent cotton farms in the South and producers of goods in the swelling Northern cities expanded operations. One result of this mass production was that the rich became richer, often flaunting their wealth. Americans increasingly spoke of class conflict.

But most leaders supported only moderate reforms. States opened the vote to all men regardless of property – while limiting that power to whites. EDITOR'S NOTE: So was the case in Rhode Island when disenfranchised white workers rebelled during the 1841-2 Dorr War. - W. Collette

Northern states began to create public education systems in part to provide for economic mobility.

None of those measures involved egalitarian redistribution; in fact, ending property requirements to vote relieved such pressures. Proposals for income or estate taxes went nowhere.

|

| Settlers like these in Custer County, Nebraska, in 1870, got free or low-cost land from the government under the Homestead Act. Bettman/Getty Images |

In 1844, the National Reform Association organized to pressure Congress to give individual settlers up to 160 acres of federal land.

The 1862 Homestead Act provided that opportunity but did not include limits on land ownership that the NRA had also wanted.

But the closest the U.S. came to deeper egalitarian reforms came a little later.

During the Civil War, Congress considered redistributing vast Southern plantations to freedmen, to punish traitors and turn the “aristocracy” into a “democracy.”

In 1865, Union General William T. Sherman implemented that idea in the coastal Southeast, giving freedmen 40-acre allotments with Army mules to help plow. But after Lincoln’s assassination, the new president, Andrew Johnson, moved to restore the plantations – and white power.

The land reform efforts continued, but most Republicans were focused on defending prewar property rights and ending military occupation of the South. In the end, Congress insisted that freedmen needed only the right to vote, and therefore passed the 15th Amendment.

Riches, and then depression

In the late 1870s, in the wake of Reconstruction, corporate power ballooned, and men like J.P. Morgan gained and flaunted stunning levels of wealth. The Revolutionary-era ideals of economic equality seemed forgotten.

Still, Americans remained hostile to concentrated wealth. In 1892, the Populist Party called for nationalizing railroads and their huge landholdings. In 1895, Alabama Congressman Milford Howard proposed limiting individual ownership of “all kinds of property” to US$1 million, with the rest forfeited to the U.S. Treasury.

Concerns about excessive wealth and power also drove anti-monopoly laws, a national income tax and the egalitarian goals of the New Deal. But the post-World War II prosperity and the “Great Society” anti-poverty programs in the 1960s and 1970s marginalized calls for deeper reforms.

Modern heirs to early ideas

As the 21st century opened, Americans again became anxious about rising economic inequality, and how wealth and power seemed increasingly dominated by a very few. At the same time, federal court rulings gave corporations more power and permitted unlimited campaign spending.

From their 18th-century perspective, America’s founding generation would view these developments as deeply corrupting. They would also recognize and applaud recent proposals for reforms, like the higher estate taxes and “wealth tax” proposed by Sen. Elizabeth Warren and others.

As Americans debate the future, it’s worth remembering that the Founders believed that the republic depended upon a rough equality of wealth.

Daniel Mandell, Professor of History, Truman State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.