Gianluca Stringhini, Boston University and Savvas Zannettou, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

|

| Trolls get creative when looking to deceive. Planet Flem/DigitalVision Vectors via Getty Images |

Even after the election, they remained active and adapted their methods, including using images – among them, easy-to-digest meme images such as Hillary Clinton appearing to run away from police – to spread their views.

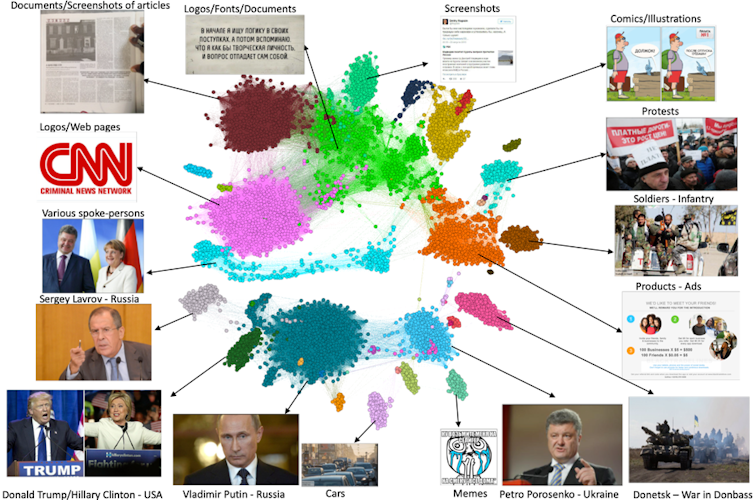

As part of our study to understand how these trolls operate, we analyzed 1.8 million images posted on Twitter by 3,600 accounts identified by Twitter itself as being part of Russian government-sponsored disinformation campaigns, from before the 2016 election through 2018, when those accounts were shut down by Twitter.

While our study focused on those specific accounts, it’s reasonable to assume that others exist and are still active. Until they were blocked by Twitter, the accounts we studied were sharing images about events in Russia, Ukraine and the U.S. – including divisive political events like the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017.

The images Russian government-backed trolls posted on Twitter appeared on other social networks, including Reddit, 4chan and Gab.

Changing focus

|

| Examples of memes shared online by Russian government- sponsored trolls. Zannettou et al., 2019., CC BY-ND |

In 2014, most of these accounts began posting images related to Russia and Ukraine, but gradually transitioned to posting images about U.S. politics, including material about Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama.

This is consistent with some of our previous analysis of the text posts of these accounts, which showed they had changed their focus from Russian foreign policy to U.S. domestic issues.

Spreading their ideas, and others’

We found that the Russian-backed accounts were both creating new propaganda and amplifying messages created by others. About 30% of the images they tweeted had not appeared on other social media or elsewhere on Twitter and were therefore likely created by the Russians behind the accounts. The remaining 70% had appeared elsewhere.

By analyzing how their posts spread across different social networks over time, we were able to estimate how much influence these accounts had on the discussions on other online services like Reddit and Gab.

We found that the accounts’ ability to spread political images varied by the social network. For instance, Russian-sponsored tweets about both parties were equally influential on Twitter, but on Gab their influence was mainly on spreading images of Democratic politicians.

On Reddit, by contrast, the troll accounts were more influential at spreading images about Republican politicians.

Looking ahead

This research is an early step toward understanding how disinformation campaigns use images. Our research provides a look at the past, but from what we have learned, we expect that information warriors will create more content themselves, and take advantage of material others create, to improve their strategies and effectiveness.

As the 2020 presidential election approaches, Americans should remain aware that Russians and others are still continuing their increasingly sophisticated efforts to mislead, confuse and spread social discord in the public.

Gianluca Stringhini, Assistant Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Boston University and Savvas Zannettou, Postdoctoral Researcher, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.