Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas delivers a coded message about

slavery.

Remember the good old days? That’s when neo-Confederates (who of

course never called themselves that; they were just defending their “heritage”)

passionately argued that the American Civil War was emphatically not about

slavery.

Remember the good old days? That’s when neo-Confederates (who of

course never called themselves that; they were just defending their “heritage”)

passionately argued that the American Civil War was emphatically not about

slavery.

Rather, it concerned issues of principle involving states’

rights, or tariff policy, or sectionalism, or internal improvements. Hell,

maybe it was about sunspots or Roscrucianism. Anything – just not slavery!

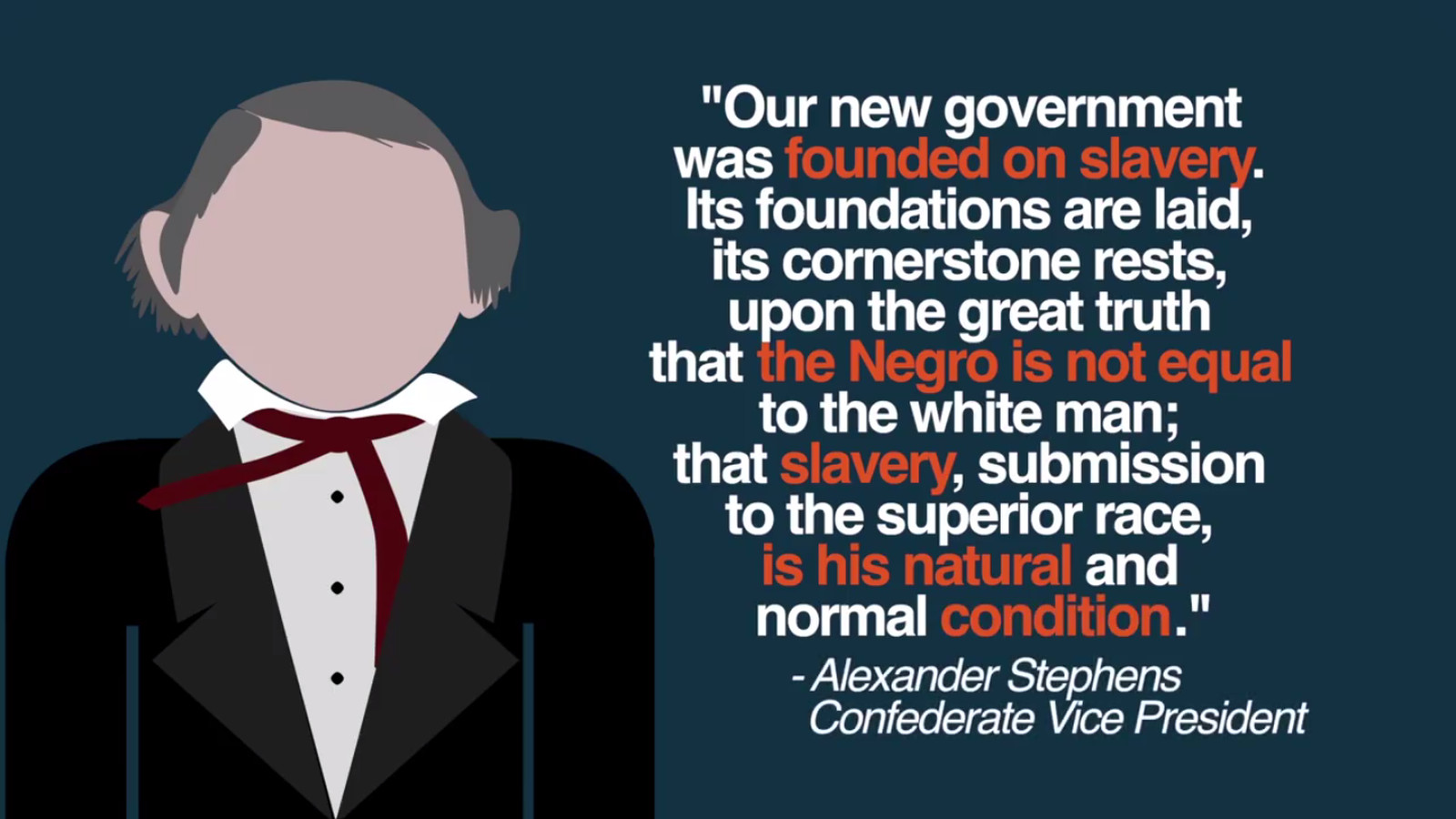

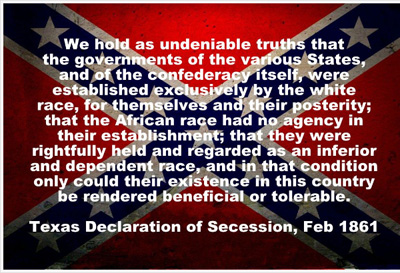

To be sure, it was frustrating talking to such people. Their

dodging and weaving around the subject of slavery was childishly obvious –

particularly given the fact that the vice president of the Confederacy,

Alexander Stevens (who certainly was in a position to be authoritative on the

subject), is principally known to history for his “cornerstone speech,” in which he declared

that the entire basis of the Confederacy was slavery:

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea [from that of the U.S. Constitution]; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.

The common denial that the Confederacy had anything to do with

slavery was, nevertheless, the hypocrisy of vice paying tribute to virtue.

The common denial that the Confederacy had anything to do with

slavery was, nevertheless, the hypocrisy of vice paying tribute to virtue. In the halcyon days of a few years ago, nobody really thought that slavery was in any way defensible; or, more cynically, no one really believed they could sell the notion that it was defensible.

That accounted for their attempt to dissociate slavery from the

Confederate cause. They were simply following in the tradition of the

Confederate memoirists of the Reconstruction era, whitewashing an odious and

treasonable movement.

But just as the Trump era has upset so many conventions that

once were believed to have been permanently settled, we now see a slightly more

robust defense of the antebellum and Civil War South, one that carefully tests

the public reaction to see what will fly.

In June, Arkansas Republican Tom Cotton wrote a now famous (or

infamous) op-ed in The New York Times in which he demanded

that the U.S. military be mobilized against citizens exercising the

constitutional right to assemble and demonstrate.

The piece quickly resulted in the resignation of The

Times’ editorial page editor, James Bennet (who it turned out had not even read the piece prior to

its printing) and a mountain of adverse publicity for the paper.

But it had more profound implications even beyond the

reprehensible argument of the op-ed itself.

Some people intuited (almost certainly correctly) that that the

piece represented more than just Cotton punking The Times. They surmised, for instance, that this was

the senator testing the waters for a potential 2024 presidential bid in which

he would try to corral the Trump voting base.

The bonus for him was the ensuing political controversy (the

Right lives off confrontation and strife), and the fact that The Times allowed

itself to be exploited in such a way as to become a fundraising vehicle for the senator.

Mission accomplished.

Cotton’s next gambit was to pick a fight with The Times (always

a crowd-pleaser with the conservative base) over the paper’s 1619 Project, an in-depth examination of

the history of slavery in America.

He introduced a bill, the Saving American History Act of 2020 which

would “prohibit the use of federal funds to teach the 1619 Project by K-12

schools or school districts.”

Cotton, who in his own mind possesses historical chops worthy of

David McCullough, stated in an interview that “the

entire premise of the New York Times’ factually, historically

flawed 1619 Project . . . is that America is at root, a systemically racist

country to the core and irredeemable.”

He goes on to say, “as the Founding Fathers said, it was the

necessary evil upon which the union was built, but the union was built in a

way, as Lincoln said, to put slavery on the course to its ultimate

extinction.”

Aside from the point that the senator did not demonstrate that

there was anything factually incorrect about the newspaper’s series, one might

note that slavery, an American historical phenomenon that already began in

1619, a year before the “foundational” landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock

(an event commemorated in a national holiday), almost certainly played a

significant role in the political and social development of the country.

Contradicting himself, Cotton then admits that slavery was

foundational, invoking the constitutional framers to proclaim it was “the

necessary evil upon which the union was built.”

He further muddies the waters by asserting that, even though the

republic was built on slavery, it was somehow built in such a clever way that

it would disappear.

To achieve that logical somersault, he quotes Lincoln, usually a

safe authority for “proving” some point or other. But Lincoln made that statement in the midst of

the 1858 Senate campaign.

In an attempt to rally anti-slavery Illinoisans, Lincoln, a

practical politician, engaged in the time-honored stump rhetoric of saying that

history and the founders were on his side.

But he did not quote the founders or provide other evidence that

the government was structured so as to initially allow slavery, and then ensure

its extinction.

Indeed, at the time, that was not the general belief. The

anti-slavery faction in the country was alarmed precisely because it feared

that slavery would expand into the U.S. Western territories, and also because,

in the wake of the Dred Scott decision, slavery could even get a foothold in

erstwhile free states.

And if the ensuing Civil War resulted in more deaths than all

other U.S. wars combined to put down a mass rebellion in favor of slavery, it

would appear to show that the “ultimate extinction” argument is logically

questionable.

But as bad, or as misleading, a historian as Cotton is, he may

have shrewdly judged the direction of the Republican base. With that in mind,

what could he have possibly meant by “necessary evil?”

A necessary evil might be physical pain which alerts the sufferer to an injury or organic dysfunction and spurs him to seek treatment, or, more abstractly, a disagreeable duty one does for the sake of the greater good.

But how was chattel slavery “necessary,” however evil it may

have been, to the founding of a constitutional republic that Cotton claims to

venerate?

Or is this more dog-whistling to his desired GOP constituency,

those who have always downplayed slavery as “not that bad” and who think that those who

still denounce the historical practice of it in America should just get over

it? And how soon, may we ask, before the fig leaf of “evil” is dropped?

Given the considerable amount of sanction for slavery in the Old Testament, along with American Christian fundamentalists’ professed belief in the Bible’s inerrancy, one ought to hesitate before claiming it impossible that we could once again see a significant segment of the Republican base (of which fundamentalist Christians are the largest single constituency) defend slavery, however much the defense might be indirect and riddled with code words. We’ve seen this before.

By the turn of the 20th century, apologias for

the “lost cause” were no longer a purely Southern affair, but were widely

accepted in the North as well (this was partly to “reconcile”

with the South during the orgy of faux-patriotism that attended

the Spanish-American War).

By Wilson’s presidency, it was firmly entrenched, and the period

approximately from The Birth of a Nation until Gone with the Wind was the

heyday of the national acceptance of slavery as a quasi-benign institution that

we had no reason to be queasy about.

There is no guarantee in history or logic that this attitude

will not return. Those who believe that the arc of history inevitably bends

towards justice – or even towards simple rationality – will have been

disappointed too many times in recent years.

Fifty years ago, it would have been inconceivable that an

American president would tout international conspiracy theories worthy

of a street-corner schizophrenic, or promote quack virus nostrums from a

“doctor” who appears to believe in voodoo. But such

is the state of the country.

If the last four years have taught us nothing else, we should

have learned that nothing, from the ridiculous to the monstrous, is

inconceivable anymore, not even a potential presidential candidate slyly

defending the history of slavery.

|

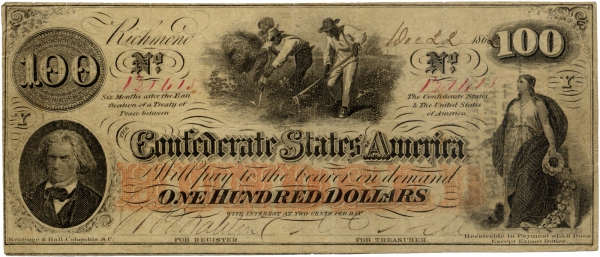

| It's right on the money. |

Mike Lofgren is a former congressional

staff member who served on both the House and Senate budget committees. His

books include: "The Deep State: The Fall of the Constitution and the

Rise of a Shadow Government" and "The Party is Over: How Republicans Went Crazy,

Democrats Became Useless, and the Middle Class Got Shafted."