Catherine Lynne Troisi, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

|

| Workers on Saturday, Aug. 29, 2020 removed the main sign to the visitors’ entrance to the CDC, leaving instead a temporary one made of cardboard-like material. Lynne Anderson, CC BY-SA |

The CDC is responsible for assuring the health of all Americans and promoting evidence-based public health practice.

It also is responsible for researching the causes of death and illness as well as working on ways to prevent them. Americans have come to trust it for accurate information.

However, recent actions by the CDC have led many in public health to call into question the integrity of the CDC’s leadership as they ignore the science and bow to political pressure. Their actions have hurt public health efforts and led to confusion and mistrust by the public at large.

As an infectious disease epidemiologist, I have spent my career both in academia and in public health practice studying how viruses infect people and testing populations to determine current infection and immunity. I find the politicization of advice coming out of the CDC disturbing, to say the least.

The latest, most egregious non-science-based advice is a change in recommendation for who should get tested for COVID-19. Here’s what happened and why it matters so much – not just to public health experts, but to the public.

Testing is key to containing the virus

|

| A digital sign in Stony Brook, New York, directs patients to the drive-thru coronavirus test site at Stony Brook University on March 28, 2020. John Paraskevas/Newsday via Getty Images |

They have learned, for example, that an estimated 4 out of 10 infected people will never show symptoms – but can unknowingly infect others.

In addition, infected persons who will go on to develop symptoms can spread the disease one to two days before those symptoms occur. These are two of the reasons the virus is so hard to contain.

Evidence suggests that widespread testing of people without symptoms would greatly reduce the spread of the virus by allowing people to know they’re infected and self-quarantine. Contacts of those asymptomatic cases can be identified and tested for the same reasons. This has been the CDC’s recommendation since studies first began to show asymptomatic transmission.

Then, the CDC on Aug. 24, 2020 changed course and recommended to test only those people who have symptoms for COVID-19.

Many public health experts were shocked. Testing only those who have symptoms will miss close to half of those who are infected.

Two days after the revised guidelines had been quietly changed on the CDC website, Director Robert Redfield clarified that those who come into contact with confirmed or probable COVID-19 patients could be tested even in the absence of symptoms.

That has always been the case, though.

In the meantime, the altered guidelines on the CDC website promote confusion and remain unchanged as of Aug. 31, 2020. Arizona, California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Texas, New Jersey and New York have already announced they will not follow the new CDC testing guidelines, showing more understanding of the benefits of testing than our national public health institution.

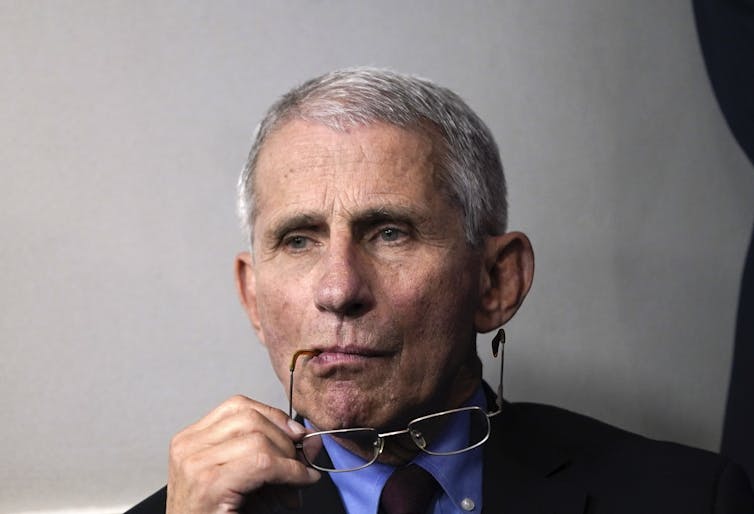

Fauci had no voice in the matter

|

| Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, listens during a briefing on the pandemic in the press briefing room of the White House. Drew Angerer/Getty Images |

Dr. Anthony Fauci, a task force member and head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, was undergoing surgery on his vocal cords when the task force met Aug. 20 and decided on the change.

The American Public Health Association has pointed out that the change was made without effective consultation with public health professionals working on the ground to control the pandemic.

The World Health Organization continues to support testing of asymptomatic persons. Nearly every public health organization has called for a reversal.

It is a particularly confusing decision given that lack of access to adequate testing has been an ongoing issue and has led to serious barriers in getting control of the pandemic.

See no virus, have no virus?

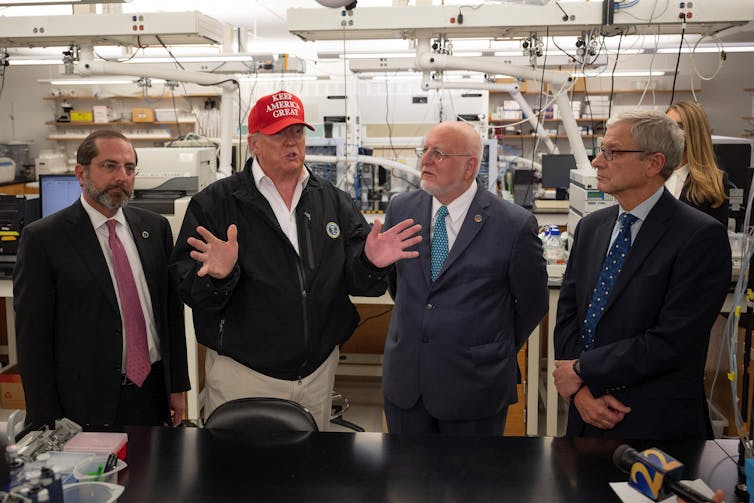

|

| Alex Azar, head of the Department of Health and Human Services, President Trump, CDC Director Robert Redfield and Associate Director Steve Monroe at the CDC in March 2020. Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images |

Identifying those who may have been exposed to the virus is the whole rationale for contact tracing – find cases, identify contacts who may have been infected, ask them to self-quarantine, and test them for the virus.

Testing is at the core of controlling infectious disease spread.

The thinking seems to be that if you don’t test, the number of cases will go down.

Clearly, this is true only in the political sense. Yes, the number of reported cases will decrease, but the number of infected persons will not. By not identifying those who are infected but don’t have symptoms, spread of the virus will increase as those who don’t know they are infected, infect others.

Trump has said that he “likes the numbers where they are” and said at a campaign rally in Tulsa that he would tell his people to “slow the testing down.”

A series of tussles

The CDC has been in the midst of a political struggle many times during this pandemic.

In May, it was revealed that CDC had been adding antibody tests, a marker of previous infection, to the number of PCR tests, a marker of current infection, performed. This made it appear that more tests to detect current infection had been performed than actually had.

In July, hospitalization data, historically reported to CDC and used by health departments and researchers throughout the country to understand the pandemic, disappeared from the CDC website as reporting switched to a private contractor. It reappeared a few days later, but this raised concerns this would hurt the ability of CDC to gather and analyze these data.

The world is now in the midst of the worst pandemic in over a century. The United States has 4.4% of the world’s population but 24% of COVID-19 cases.

Plainly, we are not doing well, and lack of trust in CDC’s guidance as well as contantly changing messaging is hampering our efforts to control the virus. No wonder the public is confused about what they should be doing.

It does not bode well if we Americans can no longer trust the advice and guidelines emanating from our national public health entity, not just for control efforts in this pandemic but for future health concerns as well.

I answer questions about COVID-19 weekly on a radio call in show. A few weeks ago a caller asked me if we could trust the information coming out of the CDC.

I never thought I would be in a position where I couldn’t give an unequivocal “yes.” When politics overcomes science, public health cannot fulfill its mission, and everyone will all suffer.

Editor’s note: Any views in this article reflect the opinion of the author and not of the University of Texas Health Science Center.

Catherine Lynne Troisi, Associate Professor of Management, Policy, and Community Health and Epidemiology, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.