Here's what states have learned so far

Tiffany A. Radcliff, Texas A&M University and Murray J. Côté, Texas A&M University

When the coronavirus began spreading in the U.S. in early spring, governors in hard-hit states took drastic steps to reduce the threat and avoid overloading their health care systems.

By shutting down nonessential businesses and schools and ordering people to stay home, they slowed the virus’s spread, but several million people lost jobs.

Since then, we’ve witnessed a series of ad hoc experiments with more targeted approaches. As states started to reopen, they tested different levels of restrictions, such as face mask mandates and capacity constraints on restaurants.

Some closed bars when cases rose again but left other businesses open. Others set restrictions that would be triggered only for hot spots when a county’s positive case numbers passed a certain threshold.

Now, as cooler weather moves more people indoors and daily case numbers rise, states and communities are looking to those successes and failures as they consider what future strategies should look like. Could more targeted closures and restrictions be effective, or will a return to statewide stay-at-home orders be needed again?

As public health researchers, we’ve been following the strategies as they evolve, and we see lessons those experiments hold for the country.

Better testing and treatment, but a long way to go

The nation’s ability to respond to the virus has improved since COVID-19 first reached U.S. cities.

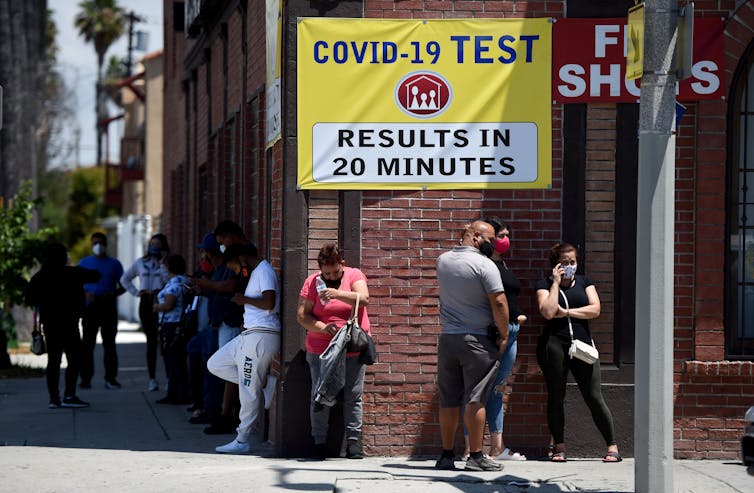

Testing capacity has expanded and results are available faster. That means people who become infected can be isolated faster. Treatment methods have also improved. For the most severe cases, innovative use of low-cost steroids and repositioning patients to support breathing have helped seriously ill patients recover faster.

However, there is still no vaccine, a lot of questions remain about new therapies, and shortages are predicted for personal protective equipment as flu season approaches.

With colder weather now arriving, the nation faces a greater potential for virus outbreaks to spread. More person-to-person contact will be inevitable with more indoor activities and in-person classes in schools and colleges.

The upcoming holidays will also mean more inside gatherings and travel. Throughout the pandemic, data have revealed a pattern of increased cases within two weeks of holidays and other events that increase contact and related exposures. For example, an uptick in cases in the Midwest was linked to late summer gatherings around Labor Day and the reopening of colleges. State and local leaders need to be prepared.

So what works?

From the nationally reported and global case data, it seems clear that requirements for social distancing and mask-wearing combined with stay-at-home orders and business closures can effectively reduce virus transmission.

New Jersey and New York initially implemented strict, prolonged measures and were able to keep case rates lower through the summer, while several states that quickly lifted restrictions saw their COVID-19 cases surge. But broadly defined shutdowns can have economic drawbacks, so governors are looking for other options.

Two types of more targeted strategies have been able to help keep the virus’s spread under control: focusing on the type of activity and on the locations where transmission risks are higher.

For example, statewide orders kept bars closed in many states since there is a greater risk when people gather in closed surroundings without masks. After Texas closed its bars, limited the number of people in restaurants and began requiring people to wear masks in public, its summer COVID-19 spike began to subside.

An MIT study in June weighed the risk of crowded conditions that could spread COVID-19 against the economic value for several activities to suggest ways to prioritize business closures. It found that those with the highest risk and lowest economic value included liquor stores, cafes, gyms, museums, theaters, sit-down restaurants and hair salons.

In some cases, decision-making about COVID-19 restrictions has largely been in local hands to respond more quickly and in a tailored way.

In most states, school districts have made the bulk of decisions about whether to hold in-person classes for K-12 students or keep their classes online.

Mayors, county judges and other local officials have also had the authority to implement emergency public health restrictions in many areas. That has allowed them to make faster, more surgical strikes against the virus’s spread in hot spots, such as shutting down beach access, restricting gatherings in neighborhoods or requiring face masks in hot-spot cities.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo ordered a mix of these tactics after COVID-19 cases flared up again in the New York City area in early October. His plan uses targeted closures of schools, bars, restaurants and certain other businesses, such as gyms, in neighborhoods with the highest density of cases. Around the edges of these hot spots, surrounding neighborhoods would face some restrictions, with the restrictions lessening with distance from the hot spot.

What’s needed to avoid future shutdowns?

Making these decisions – particularly at the level of detail planned for New York City – depends on having reliable, up-to-date data about how the virus is spreading in communities. That data is also crucial in counties that have limited health care resources but can quickly implement restrictions to slow the virus’s transmission.

While thresholds, such as positive test rates, can guide shutdowns, it may be more fruitful to focus on activities and practices that allow economies to stay open as much as possible. Protective measures such as wearing masks in public, isolating active cases and avoiding large indoor gatherings can all reduce the virus’s spread.

Communities can learn from the growing evidence and best practices to tailor their own responses and help avoid the domino effects that could send their economies into another shutdown.![]()

Tiffany A. Radcliff, Associate Dean for Research and Professor of Health Policy and Management, Texas A&M University and Murray J. Côté, Associate Professor of Health Policy and Management, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.