R.I. has Options for 100 Percent Renewable By 2030

By TIM FAULKNER/ecoRI News staff

The plan to get there is expected by the end of the year. (The Brattle Group images)

Rhode

Island’s path to achieving 100 percent renewable energy by 2030 is becoming

clearer. But there will likely be many unresolved issues once the plan is

released by the end of the year.

The

hope is that the proposal, put forth by The Brattle Group,

will offer ways the state can buy renewable energy from wind facilities and

solar arrays, either in Rhode Island or across New England.

The

report is expected to include model portfolios, policy suggestions, and

cost-benefit analyses. The second of three public webinars put numbers to the

task ahead.

Rhode Island needs about 4,440 gigawatt-hours of renewable power by 2030.

A lot more renewable energy will be needed after 2030 to cut emissions 80 percent by 2050.

One

of the most likely recommendations for meeting 100 percent by 2030 is to

increase the amount of renewable electricity National Grid buys and delivers to

customers. That mandatory level of “green” power required for the Renewable Energy Standard

(RES) is at 16 percent today. It increases to 38.5 percent by 2035.

“The

Renewable Energy Standard creates the demand for renewable energy and this is

the mechanism for tracking progress about whether you achieve [the goal] or

not,” Mike Hagerty, a senior associate for The Brattle Group, said during the Sept. 29 webinar.

National

Grid has resisted past increases to the RES, but Terry Sobolewski, president of

National Grid Rhode Island, has said “we stand ready to work with stakeholders

to make this next milestone a reality.”

The Brattle Group consultants see four main sources for acquiring renewable energy: offshore wind; onshore wind; utility-scale solar; and small-scale solar systems, referred to as distributed generation.

Nuclear power isn’t considered because it’s unlikely a new facility can be

approved and built by 2030. Large-scale hydropower from Canada was likewise

omitted due to the difficulties in approving and installing transmission lines

by 2030.

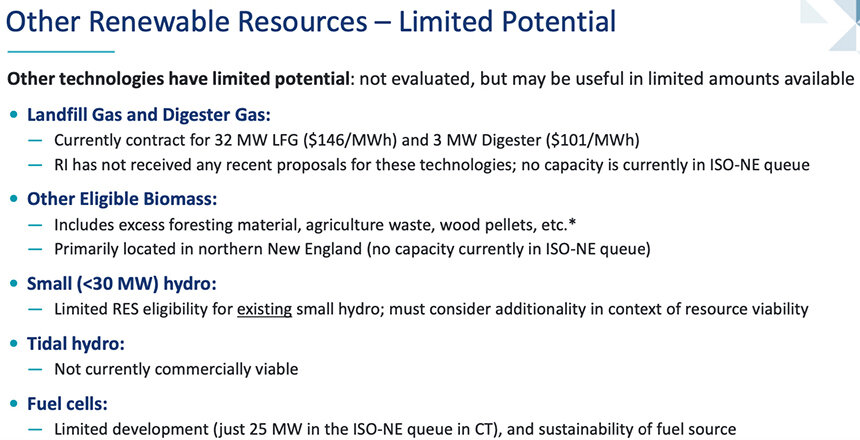

These sources are eligible but not likely to make a dent in achieving renewable-energy targets.

“We’re

not evaluating them closely because we just don’t think that they’ll play as

large a role as the other resources,“ Hagerty said.

The

final report won’t devote much analysis to health benefits because all the

models are expected to have similar health benefits. Although polluting

fossil-fuel power isn’t going away.

Rhode Island is a small producer and user of renewable energy in New England.

“The

impact of Rhode Island’s reduction in fossil demand spread across all of New

England is likely to have a fairly modest affect on the in-state production of

fossil energy,” Dean Murphy, principal at The Brattle Group, said.

Thus,

switching to 100 percent renewable energy doesn’t mean Rhode Island’s power plants

will stop operating and emitting greenhouse gases and other pollutants in 2030.

As they will “still very likely be fossil generators within the state that are

serving load for other states,” Murphy said. “They will be kept around, at

least for a while to provide reliability to the system.”

Keeping

fossil-fuel power plants online alleviates intermittency, when solar and wind

aren’t available, but the problem may get worse after 2030 when other states

ramp up their renewable-energy demand to achieve their 2050 emission-reduction

targets. At that point, there will be heightened demand for storage from

batteries, fuel cells, and pumped-storage hydroelectricity, according to

Brattle.

Environmental

justice and equity benefits will likely be realized by simply cleaning up the

power grid.

“We

are cleaning up the Rhode Island electricity system so at least the trajectory

ought to be to remove harm that might have been inflicted in the past,” said

Jürgen Weiss, of The Brattle Group.

Frontline

communities, he noted, can gain from policies that build renewable projects by

creating jobs in their neighborhoods.

Estimated costs for wind and solar customers.

|

| The next report will examine the costs and benefits of 100 percent renewable energy. |

In addition to ratepayer impacts, the next phase of the report is expected to compare these costs with the economic benefits relating to jobs, gross domestic product, and income.

Questions

were raised during the latest webinar about real-time struggles developers are

experiencing with interconnection, siting, and transmission and distribution of

building renewable-energy projects.

Weiss

noted those issues go beyond the report — and state borders.

“It’s

not in our scope in some ways to figure out what the optimal evolution is of

the Rhode Island grid or the New England grid,” Weiss said. “Figuring that out

by itself is really hard and then implementing that optimal grid expansion

would be even harder.”

Murphy

noted that, “Just staying at 100 percent [renewable energy] as the electric

load grows over time with more electrification will itself be a challenge.”

Nick

Ucci, commissioner of the Office of Energy Resources, noted that the

renewable-energy goal is connected to efforts to decarbonize heating,

transportation, and housing.

“There

are more variables than we can account for,” he said. “Technology is evolving;

we will need flexibility to adjust on the fly to achieve our long-term energy

and environmental goals. And that’s true for Rhode Island and it’s true for the

rest of the states in the region.”