Your rights do not trump public health and safety

Martha Ackelsberg, Smith College

|

| Residents line up in their cars in late November at a food distribution site in Clermont, Florida, where many are hungry because of the pandemic. Paul Hennessy/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images |

I’m a political theorist, which means I study how communities are organized, how power is exercised and how people relate to one another in and between communities.

I’ve realized – through talking to friends, and thinking about the protests against COVID-19-related restrictions that have taken place around the country – that many people do not understand that individual rights and state power are not really opposites.

The laws and policies that governments enact set the framework for the exercise of our rights. So, inaction on the part of government does not necessarily empower citizens. It can, effectively, take away our power, leaving us less able to act to address our needs.

‘War of all against all’

The Founders stated in the Declaration of Independence that “governments are instituted among Men … to secure their rights … to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Those goals cannot be pursued individually without governments to help create the conditions necessary for collective life. As Thomas Hobbes recognized almost four centuries ago, if everyone just does what they please, no one can trust anyone. We end up with chaos, uncertainty and a “war of all against all.”

Rights become worthless.

This paradox – of the need for government to enable the effective pursuit of individual aims – is particularly extreme in the situation of COVID-19 and its attendant economic crisis. Amid a rampaging pandemic, people have rights to do many things, but are they really free to exercise them?

|

| A bus reminds people ‘No Masks No Ride’ in September 2020. Ben Hasty/MediaNews Group/Reading Eagle via Getty Images |

Even more, people confront those questions from very different perspectives: “Essential” workers have had to make decisions about whether to go to work and risk disease or death, or to stay home to protect themselves and their families and risk hunger and homelessness.

Those who are unsafe in their homes, because they live with abusive parents or partners must choose between the danger of staying in and the dangers of leaving.

Even those who work remotely make an assessment of risk every time they leave home, especially now that infections have surged, given the absence of clear, shared norms about social distancing, mask-wearing and other precautions against the spread of disease.

Collective framework

Each person experiences these as personal choices, however, because federal and state governments have failed to provide a truly collective framework within which people can be safer.

People may know, for example, that if everyone wore a mask in the presence of others, maintained social distance and avoided large crowds, it would be relatively safe to be out in public. But that goal cannot be achieved by voluntary individual actions alone, since the benefits are achieved only when most or all of us participate.

The only way to assure that everyone will be wearing a mask — understood as an act of community and collective care, an action taken to protect others, as well as ourselves — is for the government to require mask-wearing because it is needed for the protection of life.

It’s well accepted that governments can mandate that drivers must have insurance if they are to be allowed to register and drive a car, or that all children be vaccinated before they can attend school.

These requirements are justified out of the recognition that our individual actions (or inactions) affect others as well as ourselves.

|

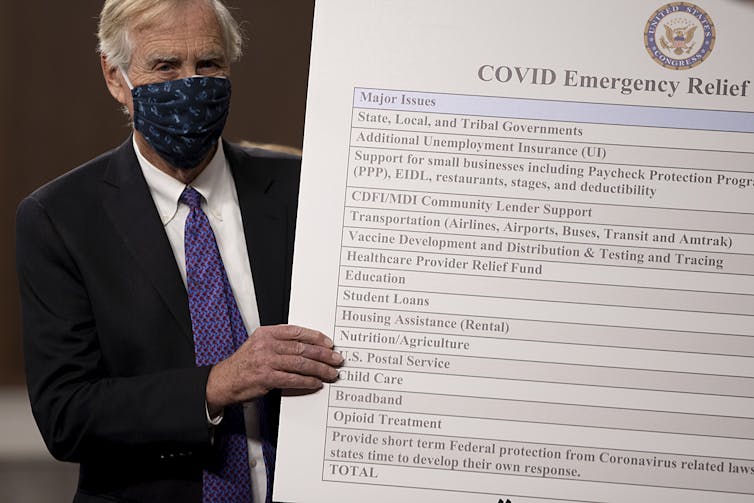

| Maine Independent Sen. Angus King sets up a sign describing a bipartisan proposal for a COVID-19 relief bill on Capitol Hill on December 1, 2020. Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images |

If businesses close to slow the spread of disease, they protect both workers and consumers.

But without government aid, they and their workers are the ones who bear the financial burdens of these actions as individuals.

Interdependence and mutual responsibility

That is why the CARES Act, which provided income for those who lost jobs and loans or grants to those who kept their workers on payroll, was critical.

It was government policy that recognized that collective caring behavior cannot be sustained without communal support. The CARES Act articulated, through a series of government programs, the idea that no one should be forced to be a martyr — say, to lose their livelihood — for the benefit of others.

Government policy of this sort (such as the relief bills now being considered by Congress) aims to ensure that those who forego work to protect others — or go to work to protect others, like essential workers — will not have to pay a personal price.

The ability to exercise the rights to work, to shop or to go to school depends upon having a relatively safe public space in which to operate. In turn, that requires all of us to attend to the rights and safety of others, as well as of ourselves.

Government is the means by which such attending — caring — is expressed and accomplished. It is only when people can count on others to be concerned for one another that they can truly be free to act, and exercise their rights, in the public arena.![]()

Martha Ackelsberg, William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Government, emerita, Smith College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.