How to Detect COVID-19 Super-Spreaders

New fluid dynamics research reveals why social distancing alone

doesn’t necessarily prevent infection indoors and how to detect COVID-19 super-spreaders.

Researchers who study the physics of fluids are learning why

certain situations increase the risk that droplets will transmit diseases like

COVID-19.

At the 73rd Annual Meeting of the American Physical Society’s

Division of Fluid Dynamics, the scientists offered new evidence showing why

it’s dangerous to meet indoors — especially if it’s cold and humid, and even if

you’re more than six feet away from other people. They suggested which masks

will catch the most infectious droplets. And they provided new tools for

measuring super-spreaders.

“Present epidemiological models for infectious respiratory

diseases do not account for the underlying flow physics of disease

transmission,” said University of Toronto engineering professor Swetaprovo

Chaudhuri, one of the researchers.

But fluids and their dynamics are critical for shaping pathogen

transport, which affects infectious disease transmission, explained

mathematical physicist and professor Lydia Bourouiba, Director of The Fluid

Dynamics of Disease Transmission Laboratory at MIT. She gave an invited

talk on the body of work she has produced over the last ten years elucidating

the fluid dynamics of infectious diseases and disease transmission.

“My work has shown that exhalations are not isolated droplets but in fact come out as a turbulent, multiphase cloud. This gas cloud is critical in enhancing the range and changing the evaporation physics of the droplets within it,” said Bourouiba. “In the context of respiratory infectious diseases, particularly now COVID-19, this work underscores the importance of changing distancing and protection guidelines based on fluid dynamics research, particularly regarding the presence of this cloud.”

Bourouiba presented examples from a range of infectious diseases including COVID-19 and discussed the discovery that exhalation involves different flow regimes, in addition to rich unsteady fluid fragmentation of complex mucosalivary fluid. Her research reveals the importance of the gas phase, which can completely change the physical picture of exhalation and droplets.

Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics scientist Dhrubaditya

Mitra and his team realized they could use the mathematical equations that

govern perfume to calculate how long it would take for viral droplets to reach

you indoors. It turns out: not very long at all.

Perfume worn by someone at the next table or cubicle reaches your nose thanks to turbulence in the air. Fine droplets spewed by an infected person spread in the same way. The researchers found that below a relative distance known as the integral scale, droplets move ballistically and very fast.

Even above the integral scale, there is danger. Consider an

example where the integral scale is two meters. If you were standing three

meters — just under ten feet — from an infected person, their droplets would

almost certainly reach you in about a minute.

“It showed us how futile most social distancing rules are once we

are indoors,” said Mitra, who conducted the research with colleague Akshay

Bhatnagar at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics and Akhilesh Kumar

Verma and Rahul Pandit at the Indian Institute of Science.

Besides traveling further and faster, droplets may also survive

longer indoors than previously believed.

Research in the 1930s analyzed how long respiratory droplets

survive before evaporating or hitting the ground. The nearly century-old

findings form the basis of our current mantra to “stay six feet away” from

others.

Physicists from the University of Twente revisited the issue. They

conducted a numerical simulation indicating that droplet lifetimes can extend more

than 100 times longer than 1930s standards would suggest.

“Current social distancing rules are based on a model which by now

should be outdated,” said physicist Detlef Lohse, who led the team.

In a cold and humid space, exhaled droplets don’t evaporate as

quickly. The hot moist puff produced also protects droplets and extends their

lifetimes, as do collective effects.

Some droplets are more likely than others to make you sick.

University of Toronto’s Chaudhuri, with researchers from the Indian Institute

of Science and the University of California San Diego, investigated why, using

human saliva droplet experiments and computational analyses.

They found that some of the most infectious droplets start out at

10 to 50 microns in size. “With certain assumptions, it appears that if

everyone wears a mask that can prevent ejection of all droplets above 5

microns, the pandemic curve could be flattened,” said Chaudhuri.

Dried droplet residue also poses a serious risk: It persists much

longer than droplets themselves and can infect large numbers of people if the

virus remains potent.

The team used their findings to develop a disease transmission

model. “Our work connects the microscale droplet physics and its fundamental

role in determining the infection spread at a macroscale,” said Chaudhuri.

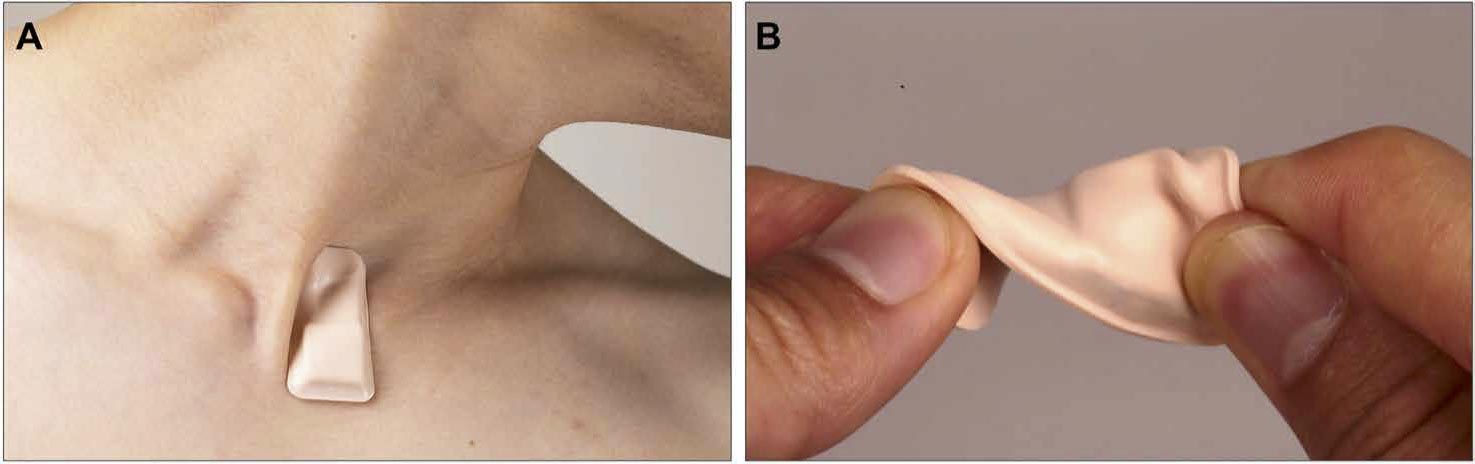

Wireless, soft, skin-interfaced sensor platform designed for mounting on the suprasternal notch. The wearable device is leading to better understanding of droplet dynamics in the COVID-19 pandemic. Credit: KunHyuk Lee, Northwestern University

To better understand droplet dynamics in the COVID-19 pandemic, a

team from Northwestern University and the University of Illinois

at Urbana-Champaign tested the capacities of a new wearable device. The thin,

wireless, flexible sensor attaches like a sticker to the bottom of the neck to

capture vital signals. Ongoing clinical studies are using the device with

hospital patients.

The team found that the device distinguishes between coughing,

talking, laughing, and other breathing activities with its machine learning

algorithms. Researchers used particle tracking velocimetry and a decibel meter

to analyze droplets produced by device wearers.

“Different types of speech can generate drastically different

numbers and dynamics of droplets,” said biomedical engineering researcher

Jin-Tae Kim, who led the investigation.

The device can help shed light on why some individuals become

unusually infectious — the so-called super-spreaders. “Our findings further

address the critical need for continuous skin-integrated sensors to better

comprehend the pandemic,” said Kim.