Could save many lives from common COVID complication

University

of Cambridge

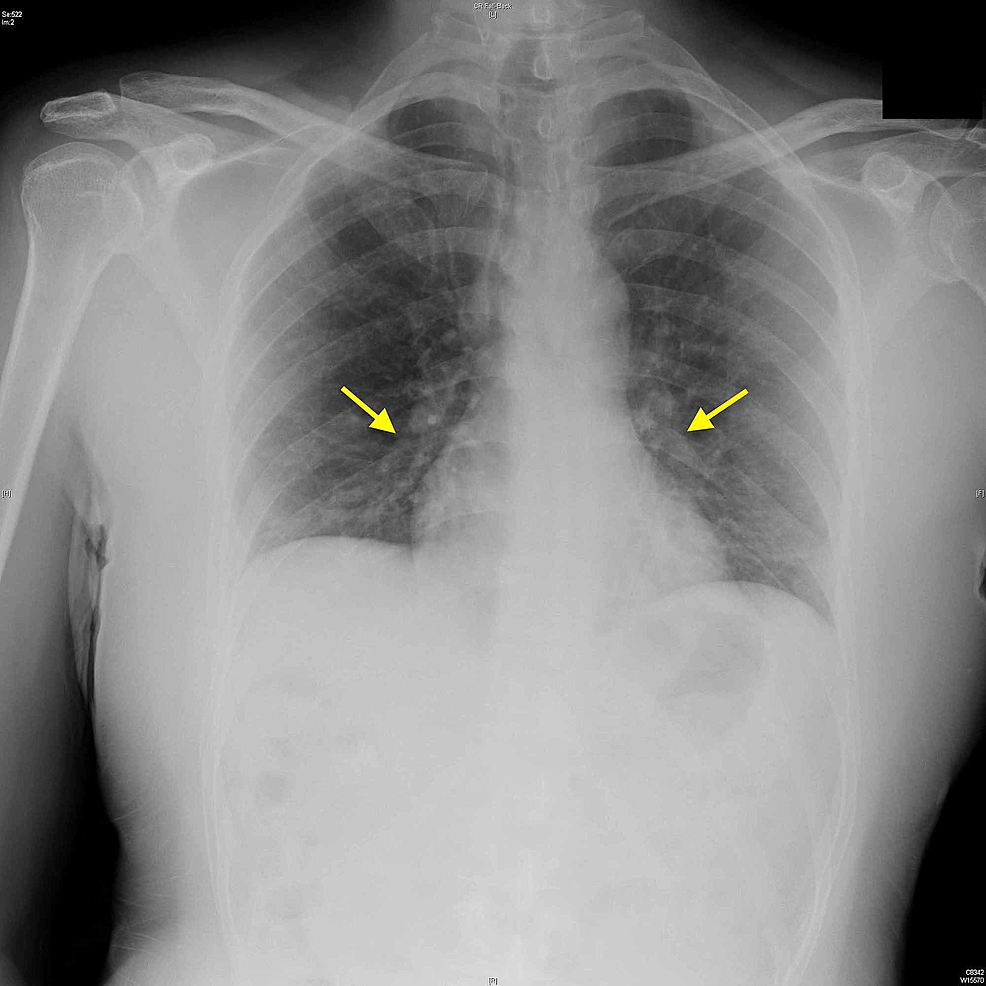

Researchers have developed a DNA test to quickly identify secondary infections in COVID-19 patients, who have double the risk of developing pneumonia while on ventilation than non-COVID-19 patients.

For

patients with the most severe forms of COVID-19, mechanical ventilation is

often the only way to keep them alive, as doctors use anti-inflammatory

therapies to treat their inflamed lungs. However, these patients are

susceptible to further infections from bacteria and fungi that they may acquire

while in hospital -- so called 'ventilator-associated pneumonia'.

Now,

a team of scientists and doctors at the University of Cambridge and Cambridge

University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, led by Professor Gordon Dougan, Dr

Vilas Navapurkar and Dr Andrew Conway Morris, have developed a simple DNA test

to quickly identify these infections and target antibiotic treatment as needed.

The

test, developed at Addenbrooke's hospital in collaboration with Public Health

England, gives doctors the information they need to start treatment within

hours rather than days, fine-tuning treatment as required and reducing the

inappropriate use of antibiotics. This approach, based on higher throughput DNA

testing, is being rolled out at Cambridge University Hospitals and offers a

route towards better treatments for infection more generally. The results are

reported in the journal Critical Care.

Patients who need mechanical ventilation are at significant risk of developing secondary pneumonia while they are in intensive care. These infections are often caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and are hard to diagnose and need targeted treatment.

"Early

on in the pandemic we noticed that COVID-19 patients appeared to be

particularly at risk of developing secondary pneumonia, and started using a

rapid diagnostic test that we had developed for just such a situation,"

said co-author Dr Andrew Conway Morris from Cambridge's Department of Medicine

and an intensive care consultant. "Using this test, we found that patients

with COVID-19 were twice as likely to develop secondary pneumonia as other

patients in the same intensive care unit."

COVID-19

patients are thought to be at increased risk of infection for several reasons.

Due to the amount of lung damage, these severe COVID-19 cases tend to spend

more time on a ventilator than patients without COVID-19. In addition, many of

these patients also have a poorly-regulated immune system, where the immune

cells damage the organs, but also have impaired anti-microbial functions,

increasing the risk of infection.

Normally,

confirming a pneumonia diagnosis is challenging, as bacterial samples from patients

need to be cultured and grown in a lab, which is time-consuming. The Cambridge

test takes an alternative approach by detecting the DNA of different pathogens,

which allows for faster and more accurate testing.

The

test uses multiple polymerase chain reaction (PCR) which detects the DNA of the

bacteria and can be done in around four hours, meaning there is no need to wait

for the bacteria to grow. "Often, patients have already started to receive

antobiotics before the bacteria have had time to grow in the lab," said

Morris. "This means that results from cultures are often negative, whereas

PCR doesn't need viable bacteria to detect -- making this a more accurate

test."

The

test -- which was developed with Dr Martin Curran, a specialist in PCR diagnostics

from Public Health England's Cambridge laboratory -- runs multiple PCR

reactions in parallel, and can simultaneously pick up 52 different pathogens,

which often infect the lungs of patients in intensive care. At the same time,

it can also test for antibiotic resistance.

"We

found that although patients with COVID-19 were more likely to develop

secondary pneumonia, the bacteria that caused these infections were similar to

those in ICU patients without COVID-19," said lead author Mailis Maes,

also from the Department of Medicine. "This means that standard antibiotic

protocols can be applied to COVID-19 patients."

This

is one of the first times that this technology has been used in routine

clinical practice and has now been approved by the hospital. The researchers

anticipate that similar approaches would benefit patients if used more broadly.

This

study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge

Biomedical Research Centre.