An expert says yes

Margaret Riley, University of Virginia

|

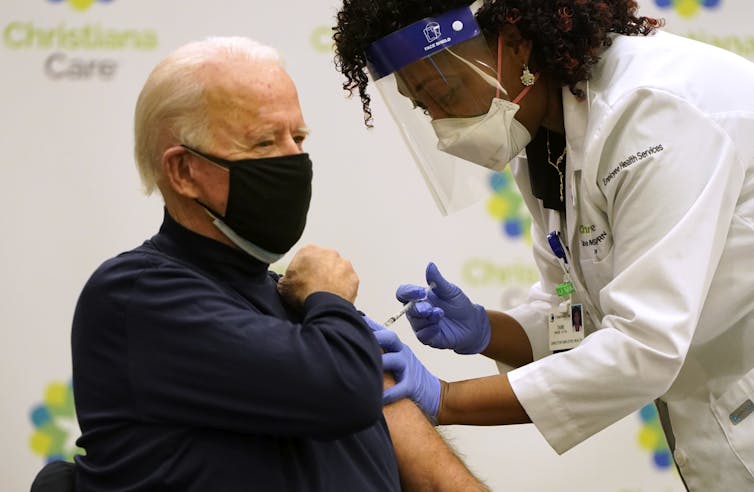

| Joe Biden, then president-elect, received his COVID-19 vaccination in December. Joshua Roberts via Getty Images |

Vaccines are the ultimate solution for the COVID-19 crisis.

If enough people are vaccinated, and the virus remains sufficiently stable, the country can hope to achieve control over the virus and people can hope to get back to something like normal life.

We’re still a long way from that, however. While estimates vary, scientists believe that we will need to vaccinate about 240 million people, which represents about 70% of the U.S. population, to achieve that kind of control.

As an expert in health law, I am troubled by the unforced errors evident in the initial vaccine rollout. They include the refusal to use the full might of the federal government and the failure to learn from past pandemic planning. By ignoring the need for state funding, preparation and guidance in the fall, the previous administration set us up to suffer a more confused and protracted rollout this winter.

|

| A man receives the COVID-19 vaccine at a school gym. Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images |

Scientists did their jobs

On one hand, the news on vaccines is better than many people imagined it could be. The two vaccines that have received emergency use authorization in the United States, one developed by Moderna and the other by Pfizer and BioNTech, have efficacy rates that are in the range of 95%.

The Food and Drug Administration had set a minimum 50% efficacy rate requirement in its vaccine guidance.

Even better, there are other promising vaccines in the pipeline, including one developed by Johnson & Johnson that is likely to obtain an emergency use authorization as soon as early February. None of this should be taken for granted; after more than 30 years of trying, scientists have not been able to achieve an effective vaccine for HIV.

On the other hand, the vaccine rollout, begun in December while the Trump administration was still in office, has been frustrating. Vaccine supply falls far short of current demand, and there is also considerable confusion about how and when individuals will be able to be vaccinated.

In early December, Operation Warp Speed, the name the Trump administration bestowed on its vaccine program, projected that 20 million Americans would be vaccinated before the end of the month.

A spokesman for Operation Warp Speed soon walked back that projection; administration officials clarified that the projection was about the number of doses that would be available, not the number of people who would actually be vaccinated.

Both authorized vaccines require two doses per person. That distinction, doses available vs. people vaccinated, captures the most significant weakness in the Trump administration’s planning.

While the administration deserves praise for supporting the development of effective vaccines in record time, it paid insufficient attention — both in planning and funding — to the public health infrastructure necessary to get the vaccine into the arms of the American people.

In President Donald Trump’s view, the federal government’s job was to deliver the vaccine to the states. After that, the states were largely on their own. And the cash-strapped states have been ill-prepared to figure it out.

Unrealistic projections and unmet expectations

The Trump administration also over-projected the amount of vaccine currently available. Operation Warp Speed had promised to deliver 300 million doses of vaccine by Jan. 1, 2021. The reality falls far short of that. The CDC said Jan. 26, 2021, that it has distributed 44.4 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines. Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna now project that they will be able to deliver 100 million doses each by the end of March.

If the Johnson & Johnson vaccine receives authorization soon, it may have as many as 100 million doses as early as April. That vaccine may require only one dose. But all of these are best-case projections.

The Biden administration promised on Jan. 21 to deliver 100 million shots in its first 100 days. That plan is both very ambitious and, for some, not ambitious enough. Under pressure to commit to a faster rollout, Biden promised on Jan. 25 to try to vaccinate 1.5 million people a day. Even if that is achieved by the end of March, we will be well short of achieving herd immunity.

To achieve even the 100 million-shot goal, more than 1 million people will need to be vaccinated each day, something that is just now happening. Getting quickly to 1.5 million vaccinations daily will be even more of an achievement.

If the vaccine manufacturers meet their production goals and the necessary public health infrastructure is put in place, we will likely surpass the 100 million-shot goal. The Biden administration needs to build trust to deal with this crisis, and it is more likely to build trust by underpromising than by overpromising and failing.

A new man, a new plan

In his first days in office, Biden has begun implementing the COVID-19 response recommended by the COVID-19 Task Force that he created as president-elect in November. A comprehensive strategic plan lays out, among other pandemic responses, how the administration intends to improve the vaccine rollout.

To deal with lagging vaccine supply, the administration intends to invoke the Defense Production Act to eliminate bottlenecks. That includes the vials, syringes, storage facilities and related products and materials necessary for delivery. Although the Trump administration invoked the use of the Defense Production Act for ventilator production early in the pandemic, it was loath to use it much going forward.

The Biden plan also calls for a US$20 billion package to provide major assistance to states for vaccine delivery and administration, including federally run vaccination centers to augment state capacities, federal assistance for the costs of vaccine administration, federal data collection, and continued federal oversight for safety and efficacy.

The plan also calls on states to simplify their vaccine priority designations. This has been an instance where the perfect has been the enemy of the good; there have been reports of vaccines thrown away rather than administered when recipients at the designated priority level were not available.

Complexity has bred confusion. At the same time, the administration has redoubled its efforts to make sure that vaccine distribution is equitable and meets the needs of underserved populations.

None of these plans is remarkable; they reflect much of the pandemic planning that was conceived, but not implemented, over the past decade. To beat COVID-19, we will have to pay for deferred public health infrastructure. Some of those funds have already been appropriated by Congress in the $900 billion COVID relief bill passed in December; more will be needed. And it will take some months to implement.

But now, there is a fully achievable vaccination plan in place, and with it, hope for a way through the COVID-19 crisis.![]()

Margaret Riley, Professor of Law, Public Health Sciences, and Public Policy, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]