By GRACE KELLY/ecoRI News staff

Not only do they provide habitat for various flora and fauna, but when managed sustainably, they provide jobs and income. They also can isolate and store carbon from the atmosphere.

“Forest really do an amazing job with air quality,” said Scott Millar, director of community assistance and conservation at Grow Smart Rhode Island.

“Forest really do an amazing job with air quality,” said Scott Millar, director of community assistance and conservation at Grow Smart Rhode Island.

“Almost 14 tons of pollutants are usually removed from the air by forests, and that pollutant removal is estimated to be worth about $30 million a year.”

But Rhode Island’s forests are being threatened from all sides.

In a recent virtual presentation hosted by the newly formed Southwestern Rhode Island Progressive Alliance (SRIPA), Millar talked about what forests give to us, why they need to be protected, and laid out some proposed suggestions to do so, as outlined in the 2019 The Value of Rhode Island Forests report.

Forest fragmentation is a growing concern. Half of Rhode Island is within the length of a football field from a road and 90 percent is within 4½ football fields of a road.

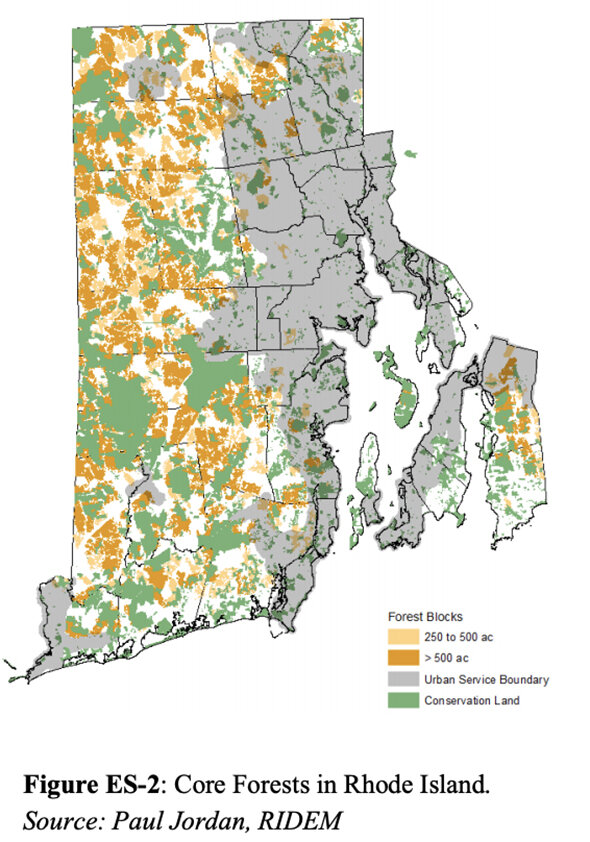

According to Millar, 56 percent of the state is forested land, but 70 percent of that land is unprotected. Showing a map of forested area, he pointed out the holes eating away at the topography.

“When you take a closer look, it’s beginning to look like Swiss cheese,” the former Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) staffer said. “You can see all these little openings in the forest, which we term forest fragmentation.”

In The Value of Rhode Island Forests report, researchers found that nearly 2,000 acres of core forest was converted to other land uses between 2011 and 2018.

Millar explained how fragmentation adversely affects the beneficial impacts the forest can have and can cause its ecosystem to become less stable.

“Forests allow wildlife to thrive,” he said during the Feb. 3 presentation. “There are over 400 species that DEM and the Wildlife Action Plan have determined are species of greatest conservation need, and those species need the unfragmented core forest to survive.”

Core forests are forests surrounded by other forests, not human development. They provide refuge and a stable home for some of Rhode Island’s most-vulnerable species, such as black-crowned night herons, bobcats, and silver-haired bats.

Beyond endangering wildlife, forest fragmentation undermines the societal effort to combat the climate crisis, with clear-cutting forests literally felling natural carbon sequesters.

“The forests are critical to meeting climate-change goals,” Millar said. “The U.S. Climate Alliance … determined that only by utilizing the power of natural lands to sequester carbon can we achieve the goal of negative emissions needed to avoid catastrophic climate change. As the impacts of climate change continued to intensify, the carbon stocks and natural lands and forests need to be safeguarded and enhanced.”

One of the greatest causes of forest loss in Rhode Island during the past several years is also a technology that is promoted for its greenness: solar energy.

“Over the last several years, more than 50 percent of our forest loss is due from solar development,” Millar said.

And while he noted that renewable energy is an important component of reducing climate emissions, he also said that we can’t sacrifice forests to make way for it. Instead, we should focus on creating and adopting responsible solar-siting ordinances.

“Renewable energy is extremely important, but renewable energy cannot remove carbon and store it. Only the forest and natural landscape can do that,” Millar said. “I think it’s clear that it’s counterproductive to be clear-cutting forests to put in utility-scale solar. It just doesn’t make any sense.”

Millar also explained a few ways the state could institute stronger forest protections.

First, there’s the upcoming special election (March 2) that contains a vote on a state beach and water bond that will put $3 million toward farmland and forest protection.

“Three million might not seem like a lot, but it’s a good starting point,” Millar said.

He also spoke about the need for a State Conservation Act. Such an act would create a Rhode Island Forests Conservation Commission headed by DEM, and would be tasked with finding new funding sources to help conserve existing forests and establish urban forests. It also would find ways to incentivize landowners to maintain and manage their land.

“Rhode Island is one of the only New England states that does not currently have a dedicated source of revenue to help protect forests,” he said. “That’s unacceptable. And we need to move forward very quickly to establish one.”

Millar underscored that we are at a critical time both globally and locally, and maintaining the 368,373 forested acres in the state has never been more crucial to the survival of the planet and the human race.

“There’s so much carbon that’s already in the atmosphere after hundreds of years of burning fossil fuels that we need to begin to aggressively remove that carbon,” he said. “We really need the forest, or we’re simply not going to be successful in achieving our climate-change goals.”

But Rhode Island’s forests are being threatened from all sides.

In a recent virtual presentation hosted by the newly formed Southwestern Rhode Island Progressive Alliance (SRIPA), Millar talked about what forests give to us, why they need to be protected, and laid out some proposed suggestions to do so, as outlined in the 2019 The Value of Rhode Island Forests report.

Forest fragmentation is a growing concern. Half of Rhode Island is within the length of a football field from a road and 90 percent is within 4½ football fields of a road.

According to Millar, 56 percent of the state is forested land, but 70 percent of that land is unprotected. Showing a map of forested area, he pointed out the holes eating away at the topography.

“When you take a closer look, it’s beginning to look like Swiss cheese,” the former Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) staffer said. “You can see all these little openings in the forest, which we term forest fragmentation.”

In The Value of Rhode Island Forests report, researchers found that nearly 2,000 acres of core forest was converted to other land uses between 2011 and 2018.

Millar explained how fragmentation adversely affects the beneficial impacts the forest can have and can cause its ecosystem to become less stable.

“Forests allow wildlife to thrive,” he said during the Feb. 3 presentation. “There are over 400 species that DEM and the Wildlife Action Plan have determined are species of greatest conservation need, and those species need the unfragmented core forest to survive.”

Core forests are forests surrounded by other forests, not human development. They provide refuge and a stable home for some of Rhode Island’s most-vulnerable species, such as black-crowned night herons, bobcats, and silver-haired bats.

Beyond endangering wildlife, forest fragmentation undermines the societal effort to combat the climate crisis, with clear-cutting forests literally felling natural carbon sequesters.

“The forests are critical to meeting climate-change goals,” Millar said. “The U.S. Climate Alliance … determined that only by utilizing the power of natural lands to sequester carbon can we achieve the goal of negative emissions needed to avoid catastrophic climate change. As the impacts of climate change continued to intensify, the carbon stocks and natural lands and forests need to be safeguarded and enhanced.”

One of the greatest causes of forest loss in Rhode Island during the past several years is also a technology that is promoted for its greenness: solar energy.

“Over the last several years, more than 50 percent of our forest loss is due from solar development,” Millar said.

And while he noted that renewable energy is an important component of reducing climate emissions, he also said that we can’t sacrifice forests to make way for it. Instead, we should focus on creating and adopting responsible solar-siting ordinances.

“Renewable energy is extremely important, but renewable energy cannot remove carbon and store it. Only the forest and natural landscape can do that,” Millar said. “I think it’s clear that it’s counterproductive to be clear-cutting forests to put in utility-scale solar. It just doesn’t make any sense.”

Millar also explained a few ways the state could institute stronger forest protections.

First, there’s the upcoming special election (March 2) that contains a vote on a state beach and water bond that will put $3 million toward farmland and forest protection.

“Three million might not seem like a lot, but it’s a good starting point,” Millar said.

He also spoke about the need for a State Conservation Act. Such an act would create a Rhode Island Forests Conservation Commission headed by DEM, and would be tasked with finding new funding sources to help conserve existing forests and establish urban forests. It also would find ways to incentivize landowners to maintain and manage their land.

“Rhode Island is one of the only New England states that does not currently have a dedicated source of revenue to help protect forests,” he said. “That’s unacceptable. And we need to move forward very quickly to establish one.”

Millar underscored that we are at a critical time both globally and locally, and maintaining the 368,373 forested acres in the state has never been more crucial to the survival of the planet and the human race.

“There’s so much carbon that’s already in the atmosphere after hundreds of years of burning fossil fuels that we need to begin to aggressively remove that carbon,” he said. “We really need the forest, or we’re simply not going to be successful in achieving our climate-change goals.”