Fermenting used food can improve crop growth

JULES BERNSTEIN

There’s

a better end for used food than taking up space in landfills and contributing

to global warming.

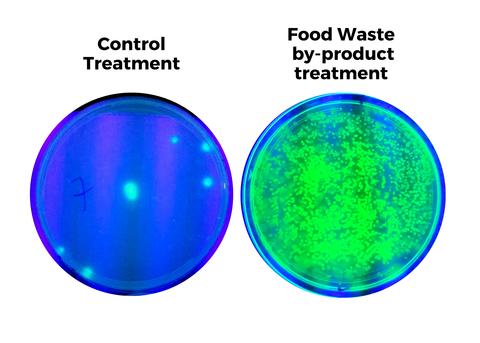

Beneficial

bacteria flourished in citrus growing systems treated with fermented waste

by-products. (Deborah Pagliaccia/UCR)

UC

Riverside scientists have discovered fermented food waste can boost bacteria

that increase crop growth, making plants more resistant to pathogens and

reducing carbon emissions from farming.

“Beneficial

microbes increased dramatically when we added fermented food waste to plant

growing systems,” said UCR microbiologist Deborah Pagliaccia, who led the

research. “When there are enough of these good bacteria, they produce

antimicrobial compounds and metabolites that help plants grow better and

faster.”

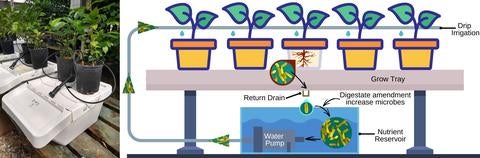

Since

the plants in this experiment were grown in a greenhouse, the benefits of the

waste products were preserved within a closed watering system. The plant roots

received a fresh dose of the treatment each time they were watered.

“This is one of the main points of this research,” Pagliaccia said. “To create a sustainable cycle where we save water by recycling it in a closed irrigation system and at the same time add a product from food waste that helps the crops with each watering cycle.”

These

results were recently described in a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Sustainable Food

Systems.

Food

waste poses a serious threat to the planet. In the U.S. alone, as much as 50%

of all food is thrown away. Most of this waste isn’t recycled, but instead,

takes up more than 20% of America’s landfill volume.

This

waste represents not only an economic loss, but a significant waste of

freshwater resources used to produce food, and a misuse of what could otherwise

feed millions of low-income people who struggle with food security.

To

help combat these issues, the UCR research team looked for alternative uses for

food waste. They examined the byproducts from two kinds of waste that is

readily available in Southern California: beer mash — a byproduct of beer

production — and mixed food waste discarded by grocery stores.

Both

types of waste were fermented by River Road Research and then added to

the irrigation system watering citrus plants in a greenhouse. Within 24 hours,

the average population of beneficial bacteria were two to three orders of

magnitude greater than in plants that did not receive the treatments, and this

trend continued each time the researchers added treatments.

UCR

environmental scientist Samantha Ying and her team then studied the carbon

dynamics and nutrients including nitrogen in the soil of the treated crops.

The analysis showed a spike in the amount of carbon in irrigation water

after being treated with waste products, followed by a sharp decrease,

suggesting the beneficial bacteria used the available carbon to

replicate.

Pagliaccia

explained that this finding has an impact on the growth of the bacteria and on

the crops themselves. “If waste byproducts can improve the carbon to nitrogen

ratio in crops, we can leverage this information to optimize production

systems,” she said.

Another

finding of note is that neither the beer mash nor the mixed food waste products

tested positive for Salmonella or other pathogenic bacteria, suggesting they

would not introduce any harmful element to food crops.

“There

is a pressing need to develop novel agricultural practices,” said UCR plant

pathologist and study co-author Georgios Vidalakis. “California’s citrus, in

particular, is facing historical challenges such as Huanglongbing bacterial

disease and limited water availability,” said Georgios Vidalakis, a UCR plant

pathologist.

The

paper’s results suggest using these two types of food waste byproducts in

agriculture is beneficial and could complement the use synthetic chemical

additives by farmers — in some cases relieving the use of such additives

altogether. Crops would in turn become less expensive.

Pagliaccia

and Ying also recently received a California Department of Food and

Agriculture grant to conduct

similar experiments using almond shell byproducts from Corigin Solutions to

augment crops. This project is also supported with funding from the California

Citrus Nursery Board, Corigin Solutions,

and by the California Agriculture and Food Enterprise.

“Forging

interdisciplinary research collaborations and building public-private sector

partnerships will help solve the challenges facing global agri-food systems,”

said UCR co-author Norman Ellstrand, a distinguished professor of

genetics.

When

companies enable growers to use food waste byproducts for agricultural

purposes, it helps move society toward a more eco-friendly system of

consumption.

“We

must transition from our linear ‘take-make-consume-dispose’ economy to a

circular one in which we use something and then find a new purpose for it. This

process is critical to protecting our planet from constant depletion of natural

resources and the threat of greenhouse gases,” Pagliaccia said. “That is the

story of this project.”