History suggests it might

Richard Amesbury, Arizona State University

|

| The big question looming over QAnon: What happens after March 4? Rick Loomis/Getty Images |

But before you circle the date and dust off the MAGA hats, a note of caution: We have been here before.

Adherents of the same conspiracy theory, QAnon, had previously marked Jan. 20, the day of Joe Biden’s inauguration, as the big day.

As Biden ascended the steps of the Capitol to take the presidential oath of office, tens of thousands of adherents of QAnon were eagerly awaiting the imminent arrest and execution of Democratic politicians in a “storm” that would upend the social and political order. It didn’t happen.

In the aftermath of this disappointment, some disillusioned QAnon followers left the fold. But as evidenced by the new date of March 4 – chosen because it was the day for presidential inaugurations until the 20th Amendment was adopted in 1933 – some hardliners claimed they had simply gotten the date wrong. When – or if – that date too passes without incident, a new date may emerge.

It might be thought that enough failed predictions would eventually discredit a prophet. But as a philosopher of religion, I know history suggests a more complicated set of possibilities.

Apocalyptic movements rarely simply dissolve when prophecies are seen to fail. Indeed, such crises have in the past presented believers with fertile opportunities to reinterpret prophecies. They have even strengthened movements, giving rise to new theories that attempt to explain the shortcomings of earlier ones.

The Millerites

This dynamic played out nearly 180 years ago with the Millerites, members of a 19th-century evangelical Christian movement who were part of an earlier “Great Awakening” in U.S. religious history.

A Baptist preacher, William Miller drew on biblical texts and numerology to predict the imminent second coming of Christ. Although Miller did not initially claim to know the exact date, he and his followers offered various predictions. As each passed without incident, the Millerites redid the Biblical math to propose new dates, until finally the movement settled on Oct. 22, 1844.

As the expected second advent drew near, many Millerites gave away their possessions in anticipation of Christ’s return.

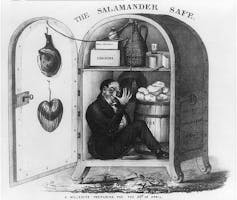

|

| A caricature of a Millerite awaiting the end of the world. Library of Congress |

When Oct. 22 came and went without incident, the Millerites were left to reconstruct a worldview that acknowledged what came to be called the “Great Disappointment.”

Miller’s followers concluded not that the Scriptures and numerology on which they had based their predictions were false, but simply that they had misunderstood their meaning.

In one view, what the predictions foretold were not earthly events, but heavenly ones.

Millerism did not collapse; rather, elements of it were central to the establishment of Seventh Day Adventism, a rapidly growing Protestant denomination that continues to look forward to Christ’s return.

Crisis point

Looking at how the Millerites dealt with their Great Disappointment gives an insight into how believers navigate what the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre calls “epistemological crises.” These are moments when the way someone understands the world is thrown into question by events that don’t fit expectations.

Epistemological crises are not unique to religion. Anyone who has experienced heartbreak in a relationship, or felt the rug pulled out from under them when unexpectedly fired by an employer, knows that they are a fact of life.

Such a crisis undercuts a person’s ability to tell the kind of story about themselves that gives order and meaning to life. Left unresolved, it threatens one’s understanding of oneself and others.

Yet, such crises don’t always prove insurmountable. MacIntyre writes, “When an epistemological crisis is resolved, it is by the construction of a new narrative, which enables the agent to understand both how he or she could intelligibly have held his or her original beliefs and how he or she could have been so drastically misled by them.”

Sometimes the new understanding repudiates the old. Often, however, the new narrative is not a radical departure from the old one, but an improvised and more sophisticated version of it – one that incorporates what had earlier seemed like outlying data points.

The Millerites, for example, survived their Great Disappointment by reaffirming their belief that God is at work in ways that humans cannot always fully anticipate.

Writing in the mid-20th century, the philosopher Antony Flew suggested that over time, religious beliefs “die the death of a thousand qualifications.” That is, they are modified beyond recognition, to the point of meaninglessness.

But scholars of religion have documented a pattern in which, rather than dying, fringe beliefs evolve, becoming more socially acceptable. As they are gradually disentangled from politics, they come to be thought of as more truly “religious.”

Making sense of disappointment

|

| Credit: Jessica McBride |

It is anyone’s guess whether QAnon will survive its current epistemological crisis. And if it does, there is no guarantee that it will emerge chastened.

Some commentators have predicted that it will return even more dangerous than before, evolving into increasingly virulent strains. It may well be subsumed within a larger conspiracy theory that seeks to explain the current disappointment in the context of an even more elaborate narrative.

Perhaps one day QAnon will take its place within the domesticated pantheon of American civil religion as another benign and depoliticized “faith.” Then again, it may simply sputter out, dying the death of a thousand qualifications.

But if history is any guide, whether QAnon survives its Great Disappointment will depend on its adherents’ ability to successfully explain to themselves how they could have been so drastically misled.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]![]()

Richard Amesbury, Professor of Religious Studies and of Philosophy and Director of the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.