From 'aliens' to 'noncitizens'

Kevin Johnson, University of California, Davis

|

| If a proposed law passes, this group of immigrants apprehended at the U.S. border near Mission, Texas, would be called ‘noncitizens,’ not ‘aliens.’ Sergio Flores for The Washington Post via Getty Images |

The country’s bedrock immigration law, the Immigration and Nationality Act, would be amended to say that “[t]he term ‘noncitizen’ means any person not a citizen or national of the United States.”

Some might think that terminology is not a big deal. But as a scholar of immigration and civil rights law, I believe that the one-word change could deeply influence Americans’ views about the rights of noncitizens and, by so doing, the future trajectory of immigration law and policy.

In forging immigration law and policy, it is far easier to deny the humanity of an “alien” than to do so for a “noncitizen.” The use of the word “alien” helps rationalize the severe treatment of noncitizens of color, from detention in cages, family separation and more.

Signaling attitude

Consider that, in restricting immigration and deportations, generations of U.S. government officials, but especially those of the fervently anti-immigrant Trump administration, frequently used the term “illegal aliens.”

For instance, President Donald Trump tweeted in 2019 that the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency “will begin the process of removing the millions of illegal aliens who have illicitly found their way into the United States.”

Officials in other presidential administrations, such as President Barack Obama’s, used “undocumented immigrant” to refer to the same people.

Similarly, use of language by Supreme Court justices telegraphs how a case will come out, as well as suggests a justice’s attitude about immigrants and their rights.

In writing for the Supreme Court in 2020 upholding deportation of an asylum seeker without a hearing, Justice Samuel Alito wrote in the first line of the opinion that “[e]very year, hundreds of thousands of aliens are apprehended at or near the border attempting to enter this country illegally.”

In contrast, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in finding in favor of the immigrants, wrote for the majority, “[t]he Court uses the term noncitizen throughout this opinion to refer to any person who is not a citizen or national of the United States.”

Targeting immigrants

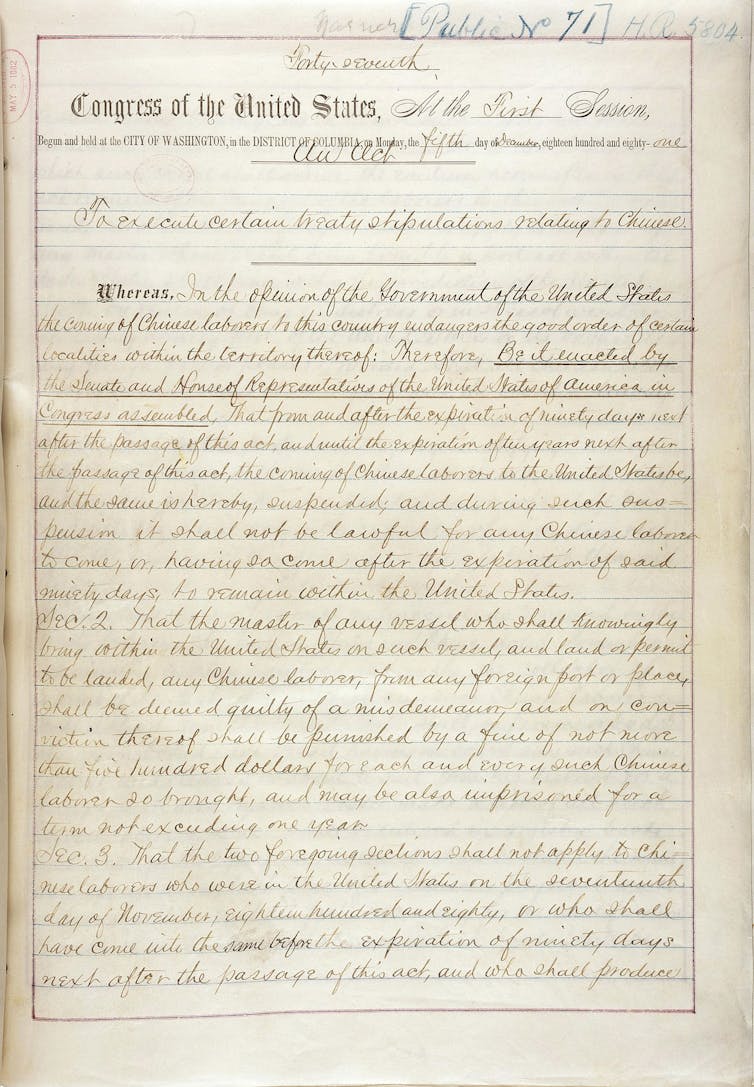

The first federal immigration legislation, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, expressly targeted Chinese immigrants for exclusion from the United States from 1882 to 1965. Over time, the terms “alien” and “illegal alien” replaced the references to the Chinese in the immigration laws.

|

| ‘No human is illegal,’ reads one demonstrator’s sign at a June 2020 San Diego rally in support of undocumented migrants, known as ‘Dreamers,’ brought to the U.S. as children. Sandy Huffaker/AFP via Getty Images |

The law governs which “aliens” may be admitted to, and deported from, the United States.

Immigration law dictates that the “term ‘alien’ means any person not a citizen or national of the United States.”

The term “illegal alien” has been criticized as a racial code for immigrants of color.. Today, “illegal alien” often is employed to refer to Mexicans and Central Americans.

“Next week ICE will begin the process of removing the millions of illegal aliens who have illicitly found their way into the United States,” former President Donald Trump said in mid-2019.

Late in the 2020 presidential campaign, Trump aide Stephen Miller tried to discredit Biden’s immigration policies by saying that Arizona, for example, “will be overwhelmed by hundreds of thousands, millions of illegal immigrants because they get apprehended, they get issued a court date and they get released.”

Terminology matters

In a law review article published more than 20 years ago, I criticized the dehumanizing impacts of alien terminology and how it helps to rationalize the harsh treatment of people:

“Citizens have a large bundle of political and civil rights, many of which are guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution; aliens have a much smaller bundle and enjoy far fewer constitutional and statutory protections…. [T]he use of the term alien helps to reinforce and strengthen nativist sentiment toward members of new immigrant groups, which in turn influences U.S. responses to immigration and human rights issues.”

The legal creation of the “alien” helps to justify the fact that our legal system offers noncitizens only limited rights. Constitutional law scholar Alexander Bickel noted that the use of terms that dehumanize people helps justify the denial of rights because it is easier to deny rights to a nonperson.

Consider the public debate. Advocates of immigration enforcement claim that today’s faceless “illegal alien” invaders must be stopped. For example, Ken Cuccinelli, the acting director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services in the Trump administration, was a founder of a group more than a decade ago that described “illegal aliens” as “foreign invaders” responsible for “serious infectious diseases, drug running, gang violence, human trafficking, terrorism.”

The Federation for American Immigration Reform, an advocacy group that works to limit immigration, recently issued a press release announcing that “Illegal Alien Population Soars to a Record 14.5 Million Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic.”

Glenn Spencer, the president and founder of American Border Patrol, an advocacy group that tracks migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, has said that “[e]very illegal alien in our nation must be deported immediately. …”

Although a seemingly minor and technical change, the elimination of “alien” from the U.S. immigration laws might transform the entire discussion of immigrants.

Terminology matters. Humans, not faceless invaders, are affected by the immigration laws. “Noncitizen” is more neutral than “alien.” On this score, the U.S. Citizenship Act would take a small but important step toward treating immigrants with humanity.![]()

Kevin Johnson, Dean and Professor of Public Interest Law and Chicana/o Studies, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[The Conversation’s Politics + Society editors pick need-to-know stories. Sign up for Politics Weekly.]