Many QAnon followers report having mental health diagnoses

Sophia Moskalenko, Georgia State University |

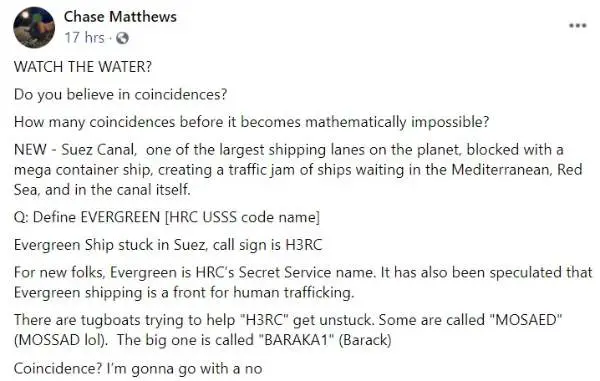

| Here's a new Q-Anon cause for alarm: the giant tanker stuck in the Suez Canal is actually a ship owned by Hillary Clinton and used for smuggling children being trafficked for sex. The message above is one Q follower's analysis. |

QAnon followers, who may number in the millions, appear to believe a baseless and debunked conspiracy theory claiming that a satanic cabal of pedophiles and cannibals controls world governments and the media.

They also subscribe to many other outlandish and improbable ideas, such as that the Earth is flat, that the coronavirus is a biological weapon used to gain control over the world’s population, that Bill Gates is somehow trying to use coronavirus vaccinations to implant microchips into people and more.

As a social psychologist, I normally study terrorists. During research for “Pastels and Pedophiles: Inside the Mind of QAnon,” a forthcoming book I co-authored with security scholar Mia Bloom, I noticed that QAnon followers are different from the radicals I usually study in one key way: They are far more likely to have serious mental illnesses.

Significant conditions

I found that many QAnon followers revealed – in their own words on social media or in interviews – a wide range of mental health diagnoses, including bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety and addiction.

In court records of people arrested in the wake of the Capitol insurrection, 68% reported they had received mental health diagnoses.

The conditions they revealed included post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, paranoid schizophrenia and Munchausen syndrome by proxy – a psychological disorder that causes one to invent or inflict health problems on a loved one, usually a child, in order to gain attention for themselves. By contrast, 19% of all Americans have a mental health diagnosis.

Among QAnon insurrectionists with criminal records, 44% experienced a serious psychological trauma that preceded their radicalization, such as physical or sexual abuse of them or of their children.

The psychology of conspiracy

Research has long revealed connections between psychological problems and beliefs in conspiracy theories. For example, anxiety increases conspiratorial thinking, as do social isolation and loneliness.

Depressed, narcissistic and emotionally detached people are also prone to have a conspiratorial mindset. Likewise, people who exhibit odd, eccentric, suspicious and paranoid behavior – and who are manipulative, irresponsible and low on empathy – are more likely to believe conspiracy theories.

QAnon’s rise has coincided with an unfolding mental health crisis in the United States. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of diagnoses of mental illness was growing, with 1.5 million more people diagnosed in 2019 than in 2018.

The isolation of the lockdowns, compounded by the anxiety related to COVID and the economic uncertainty, made a bad situation worse. Self-reported anxiety and depression quadrupled during the quarantine and now affects as much as 40% of the U.S. population.

|

| Supporters of President Donald Trump hold up their phones with messages referring to the QAnon conspiracy theory at a campaign rally at the Las Vegas Convention Center on Feb. 21, 2020. Mario Tama/Getty Images |

A more serious problem

It’s possible that people who embrace QAnon ideas may be inadvertently or indirectly expressing deeper psychological problems.

This could be similar to when people exhibit self-harming behavior or psychosomatic complaints that are in fact signals of serious psychological issues.

It could be that QAnon is less a problem of terrorism and extremism than it is one of poor mental health.

Only a few dozen QAnon followers are accused of having done anything illegal or violent – which means that for millions of QAnon believers, their radicalization may be of their opinions, but not their actions.

In my view, the solution to this aspect of the QAnon problem is to address the mental health needs of all Americans – including those whose problems manifest as QAnon beliefs. Many of them – and many others who are not QAnon followers – could clearly benefit from counseling and therapy.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Sophia Moskalenko, Research Fellow in Social Psychology, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.