Maybe the end of the pandemic

Katherine A. Foss, Middle Tennessee State University

|

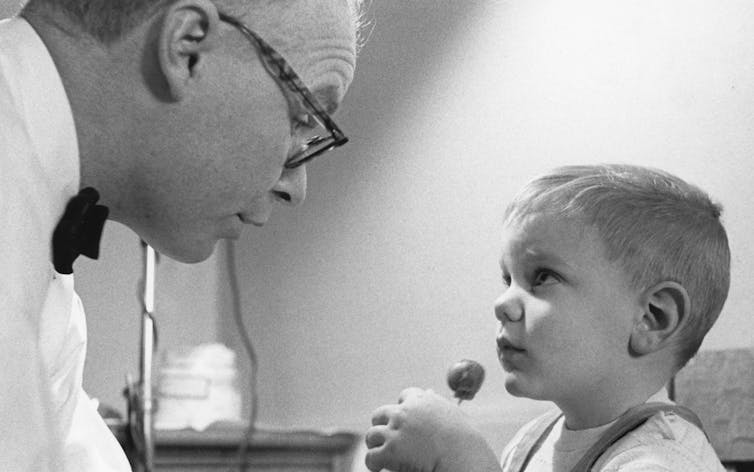

| An unidentified doctor talks with a boy who holds a lollipop reward after participating in a measles vaccine research program in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, in 1963. NASA/PhotoQuest/Getty Images |

How is the government going to get people on board? From my research, I have found that an important part of a successful vaccine campaign is in the name.

As a health communication scholar who studies the history of epidemics, I have been interested in the naming and public delivery of the COVID-19 government response. In many ways, this moment parallels crises of the past, as people in previous epidemics and pandemics also struggled to find ways to protect themselves against deadly disease.

|

| Dr. Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, speaking about Zika in January 2016. Win McNamee/Getty Images |

Abandoning the ‘Operation Warp Speed’ name

In the week leading up to the 2021 presidential inauguration, the Biden transition team announced that the White House’s national COVID-19 vaccine plan would no longer be called “Operation Warp Speed,” the name coined by Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump.

On Jan. 21, 2021, the Biden administration released its 200-page COVID-19 plan, “The National Strategy for the COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness.”

The change in names not only broadened the focus to include additional safety measures to curb transmission during the distribution process. It also signified a profound shift in the administration’s approach and consideration of the pandemic itself.

Dr. Anthony Fauci and other public health experts criticized the “Operation Warp Speed” name, arguing that it falsely conveyed a lack of scientific rigor and adherence to safety protocol in the vaccine approval process.

In a May 15, 2020, press conference, Trump explained the campaign name, stating, “It’s called ‘Operation Warp Speed.’ That means big, and it means fast. A massive scientific, industrial and logistical endeavor unlike anything our country has seen since the Manhattan Project.”

Fauci and others believed that the name “Operation Warp Speed” could have undermined public trust in any COVID-19 vaccine to be developed, feeding into theories and misconceptions of the anti-vaccine movement.

It also marked a historical deviation in the identification of vaccine campaigns for the general public. The names we Americans use broadly today, inoculation and vaccination, emerged as the names for very specific immunization procedures against a specific disease, smallpox.

Smallpox: A big controversy

In the past, immunization terms stemmed from the induced immunological protection against smallpox.

During the Boston smallpox epidemic of 1721, for example, Puritan minister Cotton Mather and Colonial physician Dr. Zabdiel Boylston introduced the practice of inoculation in hopes of protecting the town. Onesimus, an enslaved man who was in bondage to Mather, had told Mather of the practice and how he had been inoculated as a child in Africa.

The practice involved intentionally infecting people with smallpox in hopes of reducing its severity.

People fiercely discussed this controversial approach in public discourse, even spurring James Franklin, older brother of Benjamin, to create the New England Courant as an outlet to oppose its practice.

Many articles in The Courant, Boston Gazette and the Boston News-Letter, along with pamphlets, argued for and against the practice of inoculation. This cemented the term in 18th-century vocabulary, along with its alternative name, “variolation.”

This practice, and growing public familiarity with it, set the stage for acceptance of the first vaccine, which would change the course of disease. In 1798, English physician Dr. Edward Jenner proposed that inducing a mild cowpox infection could protect against smallpox – which he called a “vaccine,” from vaccinia, meaning cowpox.

|

| Millions of people already have been vaccinated. Michael Ciaglo/Getty Images |

Immunization campaigns for approved and established vaccines have often gone unnamed, simply listing the disease name, location and date, like the 1916 typhoid vaccine campaign in North Carolina’s Catawba County, northwest of Charlotte, North Carolina.

Even sponsored vaccine programs have not necessarily taken on the name of the supporting corporation.

In 1926, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. donated US$15,000 toward the eradication of diphtheria in New York. Despite this contribution, the campaign went unnamed.

In the trial and development stage, vaccines were not typically named, even in the press. News articles referred to the “anti-disease” vaccine – that is, “anti-smallpox,” “anti-typhoid,” “anti-tetanus” – sometimes including the lead scientist’s last name, as with the Enders measles vaccine.

For example, although polio vaccine trials in 1954 labeled the recruited child participants “polio pioneers,” the vaccine itself was called the “anti-polio” or Salk vaccine.

Nicknaming vaccines can be a problem

When vaccine campaigns have been named, catchy or abstract names can be problematic, especially in the experimental stages. The 1950s gamma globulin trials prompted confusion with the nickname “Operation Lollipop,” which referred to the “all-day sucker” given to children after the injection.

Some people misunderstood, believing that scientists had delivered the actual polio virus in the candy to participants, prompting clarification that the name “had nothing to do with the experiment itself.”

|

| A Star Wars poster from 1977 encouraged immunization. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

More often, campaigns and slogans have been used in catch-up immunization drives after already widely distributed vaccines, as in the polio vaccine “Wellbee,” Utah’s 1967 “Muzzle Measles,” the 1977 Star Wars “Parents of Earth” message or the 1997 Dr. Seuss Immunization Awareness Campaign.

These programs highlighted the importance of existing vaccines, rather than introducing new ones.

As public health officials have noted, the title “Operation Warp Speed,” combined with the lack of a strategic COVID-19 response plan under the Trump administration, took away from the strict adherence to safety protocols that vaccine producers and the Food and Drug Administration have followed.

In a Gallup Panel survey from Dec. 15, 2020, to Jan. 3, 2021, 65% of participants said they would get the vaccine, with divisions in age, race, education and party affiliation.

The name “Operation Warp Speed” paired with coronavirus misinformation, much of it directly from Trump, likely contributed to the lack of trust in the vaccines before they were even developed.

At least 75% to 80% of the population needs to become immunized – the number needed for herd immunity – to end of the pandemic, according to Fauci. Thus, I believe it will be important to develop a trustworthy campaign and a name that bolsters confidence.

The Biden administration is not starting from scratch. I believe that the Biden administration’s adoption of a new direct name for its response plan is the first step toward pandemic recovery.

Building confidence across various groups and communities will be critical for herd immunity to be achieved. The new campaign name, then, initiated what needs to be a straightforward, factual approach, integral to widespread COVID-19 immunization.![]()

Katherine A. Foss, Professor of Media Studies, Middle Tennessee State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.