Decellularized spinach serves as an edible platform for laboratory-grown meat

Boston College

|

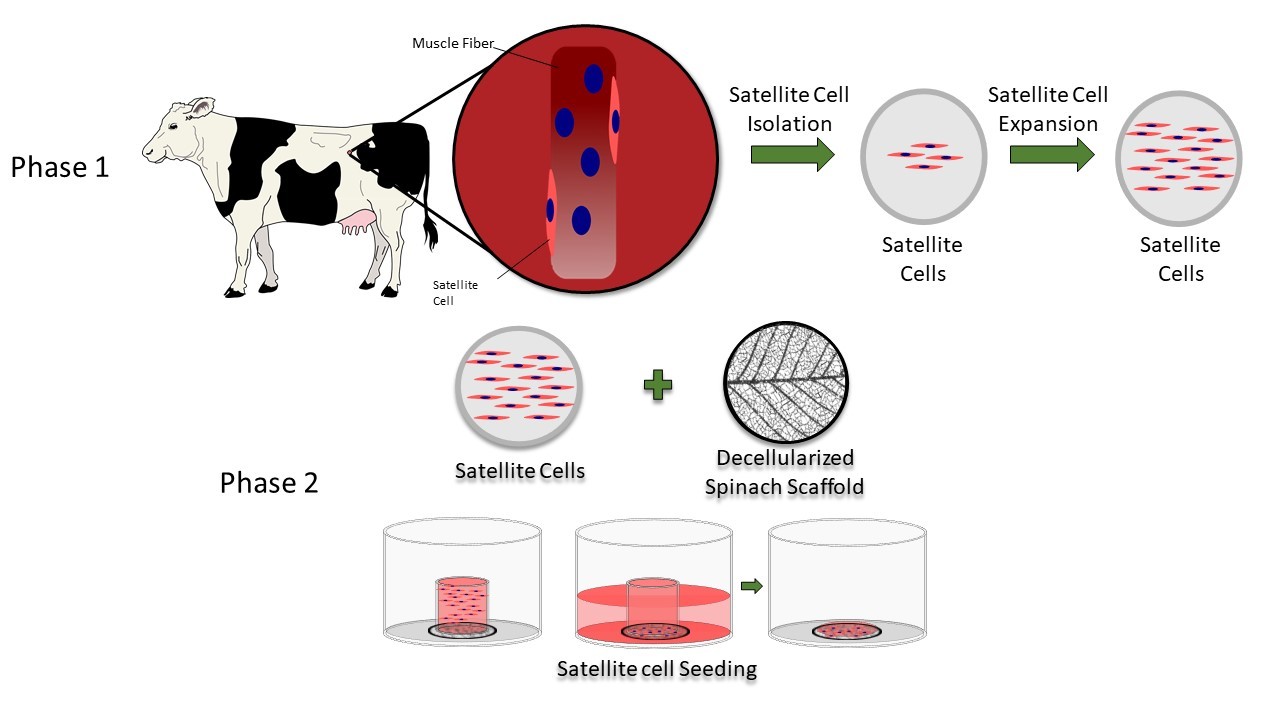

| This diagram shows the steps researchers took to isolate and seed primary bovine satellite cells on a decellularized spinach leaf scaffold. |

Spinach, a cost-efficient and environmentally friendly scaffold, provided an edible platform upon which a team of researchers led by a Boston College engineer has grown meat cells, an advance that may accelerate the development of cultured meat, according to a new report in the advance online edition of the journal Food BioScience.

Stripped

of all but its veiny skeleton, the circulatory network of a spinach leaf

successfully served as an edible substrate upon which the researchers grew

bovine animal protein, said Boston College Professor of Engineering Glenn

Gaudette, the lead author of the new study. The results may help increase the

production of cellular agriculture products to meet rising demand and reduce

environmental costs.

"Cellular agriculture has the potential to produce meat that replicates the structure of traditionally grown meat while minimizing the land and water requirements," said Gaudette, the inaugural chair of BC's new Engineering Department. "We demonstrate that decellularizing spinach leaves can be used as an edible scaffold to grow bovine muscle cells as they develop into meat."

Earlier

advances by Gaudette in this area garnered worldwide attention. In 2017, Gaudette

and a multi-university team showed that human heart tissue could be cultivated

on a spinach leaf scaffold, which was chosen because it offered a natural

circulatory system that is nearly impossible to replicate with available

scientific tools and techniques.

"In

our previous work, we demonstrated that spinach leaves could be used to create

heart muscle patches," said Gaudette. "Instead of using spinach to

regrow replacement human parts, this latest project demonstrates that we can

use spinach to grow meat."

Gaudette

said the team, which included Worcester Polytechnic Institute graduate students

Jordan Jones and Alex Rebello, removed the plant cells from the spinach leaf

and used the remaining vascular framework to grow isolated cow precursor meat

cells. The cells remained viable for up to 14 days and differentiated into

muscle mass.

"We need environmentally and ethically friendly ways to grow meat in order to feed the growing population," said Gaudette, whose research is supported by New Harvest.

"We set out to see if we can use an edible scaffold to accomplish

this. Muscle cells are anchorage dependent, meaning they need to grab on to

something in order to grow. In the lab, we can use plastic tissue culture

plates, but plastic is not edible."

The

researchers point out that the successful results will lead to further

characterization of the materials and scientific processes to better understand

how to meet consumer demand and gauge how large-scale production could be

accomplished in accordance with health and safety guidelines.

"We

need to scale this up by growing more cells on the leaves to create a thicker

steak," said Guadette. "In addition, we are looking at other

vegetables and other animal and fish cells."