South County Coastline Fades Away as Carbon Emissions Pile Up

By FRANK CARINI/ecoRI News staff

Along

the Rhode Island coast from Watch Hill to Point Judith, change is happening

fast. From 5,000 to 150 years ago, coastal erosion along this stretch of

open-ocean shoreline held steady, but it accelerated as our fondness for

burning fossil fuels grew.

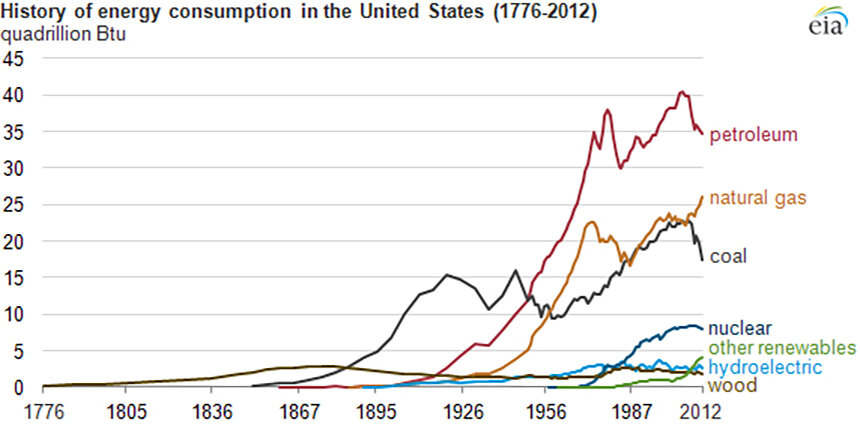

Coal

became dominant in the late 19th century before being overtaken by petroleum

products, such as oil, gasoline and diesel, in the middle of the past century.

Natural gas is now the dominate fossil fuel.

The buildup of greenhouse-gas emissions in the atmosphere has taken a bite out of the Ocean State’s South County coast. Erosion rates are increasing and the volume of sand is decreasing, according to John King, a longtime professor at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

Beaches and the

sand upon them protect the land behind them. Rhode Island is losing a natural

defender of its developed coastline, and upland sand resources won’t last

forever, even if taxpayer funding could.

|

| The three major fossil fuels — coal, petroleum and natural gas — have dominated the U.S. fuel mix for more than a century. (EIA) |

EDITOR'S NOTE: In its frantic fight to block the unpopular Whalerock industrial wind turbine project from being built along the ridgeline north of Route One, Charlestown embraced a fact-free position opposing ALL wind energy and effectively banning even small residential wind generators. This was done by enacting Ordinance 344 in November 2011 that set conditions that made it impossible to install a residential wind generator of any kind. In the 10 years since that ordinance was enacted, not one single permit has been issued by Charlestown to install a residential wind generator. - Will Collette

King said these accelerating erosion rates are tied to the relentless burning of fossil fuels during the past century and a half that has the level of atmospheric carbon at nearly 420 parts per million. Science considers a safe level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — meaning one that supports human existence — to be no more than 350 parts per million.

King

and his revolving team of URI researchers have been monitoring coastal changes

at eight Ocean State beaches from Westerly to Narragansett since the mid-1990s.

Decades of data show a highly developed shoreline eroding at a significant

rate. South Kingstown Town Beach and Green Hill Beach are eroding faster than

other places along the South County coast, according to King.

In

the early 1960s the late Robert McMaster, a well-respected professor and

researcher in the field of marine geology, initiated the URI beach monitoring

project. It started with four sites and grew to its current eight. King took

over these biweekly beach profiles — in June, July and August they are only

performed once a month — after McMaster’s death in 1993.

At

6-decades-old, it’s the world’s longest running beach profiling study,

according to URI. The project’s data were used in creating the Coastal

Resources Management Council’s nationally recognized Shoreline Change Special

Area Management Plan, better known as the Beach SAMP.

The

rate of sea-level rise, according to the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration (NASA), has risen from about 0.1 inch (2.5

millimeters) a year in the 1990s to about 0.13 inches (3.4 millimeters) a year

now. It may not seem like much, but a few millimeters matter. It will matter

even more when millimeters turn into centimeters.

King

said when sea-level rise is less than 2.5 millimeters a year “beaches don’t

retreat that rapidly and stay roughly in the same place.” That’s not what is

happening now, neither along Rhode Island’s southern shore nor across the

globe.

NASA notes that every

inch of sea-level rise results in the loss of about 100 inches (8.3 feet) of

beach. Locally, sea levels have risen nearly a foot since the 1930s. The rate

of sea-level rise is also accelerating as increasing amounts of mountain

glaciers and ice sheets melt and ocean waters warm. Rhode Island, like much of

the rest of the Atlantic Coast, is in a sea-level-rise hot spot.

King

said sea levels are rising rapidly, in geologic time, and the combination of

this rise with more frequent severe weather and intense storms that linger

longer are steadily damaging the coast. With the amount of carbon already baked

into the atmosphere, these coastal beatings won’t be ending anytime soon.

Continued burning of fossil fuels will only prolong the assault.

|

| Erosion rates at beaches along Rhode Island’s open-ocean coast, including in Charlestown, are increasing, and the volume of sand on those beaches is decreasing. (Tom Wojick/for ecoRI News) |

Laser focused

It’s not easy to eyeball sea-level rise at your local beach — URI’s

beach-monitoring project has relied on changing technology — but its impacts

are being felt in multiple ways: shoreline loss, coastal wetland inundation and

dune flattening. Coastal lagoons are being filled in, and waves are “hitting

the mainland with significant energy.”

“It’s

not a good situation,” King said.

He

noted Rhode Island, based on a few thousand years of recurrence interval data,

gets hit by a Category 3 or stronger hurricane every 60-70 years. The last

Category 3 hurricane was Carol in 1954, 67 years ago. We’re due, and when it

strikes, King said “we’re in trouble.”

“A

fair amount of unpleasant things are going to happen,” he said.

King

and his team now monitor coastal changes using light detection and ranging (LiDAR) technology. The expensive equipment

works by shooting a laser, from a boat traveling about 3-4 knots per hour, at

the shore, which bounces back to a detection sensor. Hard or reflective

surfaces return more light than soft, absorbent ones. The result is a dense

group of points, each with a latitude, a longitude and an elevation.

With

this data, King and other scientists can see exactly what a beach looked like

at the time of the survey, and can figure out how much sand there was and

where.

The

increased speed of LiDAR allows more flexibility for when data is collected,

such as immediately after a big storm. It also doesn’t require a U.S. Fish

& Wildlife escort in the summer to make sure the nests of piping plovers

aren’t disturbed.

With

the changes his work has documented during the past three decades and the full

collection of data amassed during URI’s ongoing beach monitoring project, King

said Rhode Island shouldn’t be fooled into thinking engineering solutions are

the panacea. He also noted policy change often takes too long, even when the

political system is working.

Besides

the obvious need to drastically cut greenhouse-gas emissions here and across

the globe, climate solutions, at least when it comes to living, working and

playing along the Rhode Island coast, will require retreating from the shore,

buying out properties and letting nature take over, halting development in

vulnerable areas, relocating roads and moving critical infrastructure such as

water mains and wastewater systems.

To

address the former, King said offshore wind and the electrification of the

transportation and heating sectors play vital roles. For the latter, he said,

“We should already be in the triage process, determining what we can do and

what we can give up.”

But

time is running out to get a handle on the climate crisis.

“We

pissed away most of the time we had to address these impacts,” said King,

noting the time for easy answers has passed. “A greater sense of urgency is

required.”