It's all about the muscle

Libby Richards, Purdue University

|

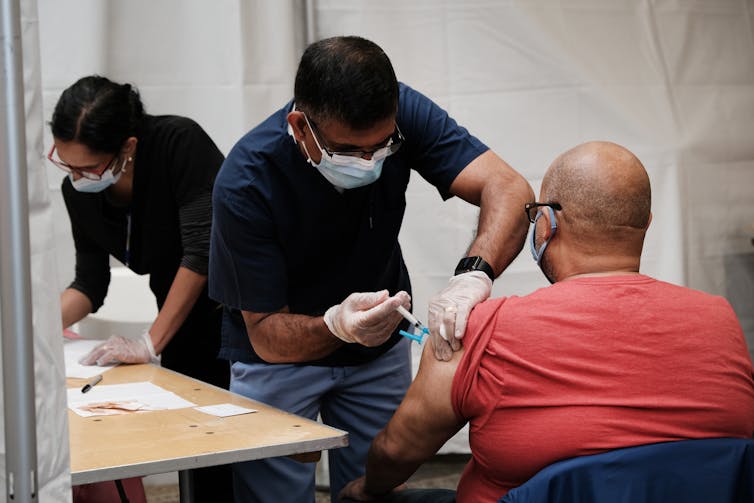

| A man receives the COVID-19 vaccine in Lima, Peru. Carlos Garcia Granthon/Fotoholica Press/LightRocket via Getty Images |

As an associate professor of nursing with a background in public health, and as a mother of two curious kids, I field this question fairly often. So here’s the science behind why we get most vaccines in our arm.

It’s worth noting that most, but not all, vaccines are given in the muscle – this is known as an intramuscular injection.

Some vaccines, like the rotavirus vaccine, are given orally. Others are given just beneath the skin, or subcutaneously – think of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine. However, many others are given in the muscle.

But why is the muscle so important, and does location matter? And why the arm muscle – called the deltoid – in the top of the shoulder?

Muscles have immune cells

Muscles make an excellent vaccine administration site because muscle tissue contains important immune cells. These immune cells recognize the antigen, a tiny piece of a virus or bacteria introduced by the vaccine that stimulates an immune response.

In the case of the COVID-19 vaccine, it is not introducing an antigen but rather administering the blueprint for producing antigens. The immune cells in the muscle tissue pick up these antigens and present them to the lymph nodes. Injecting the vaccine into muscle tissue keeps the vaccine localized, allowing immune cells to sound the alarm to other immune cells and get to work.

Once a vaccine is recognized by the immune cells in the muscle, these cells carry the antigen to lymph vessels, which transport the antigen-carrying immune cells into the lymph nodes. Lymph nodes, key components of our immune system, contain more immune cells that recognize the antigens in vaccines and start the immune process of creating antibodies.

Clusters of lymph nodes are located in areas close to vaccine administration sites. For instance, many vaccines are injected in the deltoid because it is close to lymph nodes located just under the armpit. When vaccines are given in the thigh, the lymph vessels don’t have far to travel to reach the cluster of lymph nodes in the groin.

|

| It’s much easier to roll up one’s shirt sleeve than to drop one’s drawers – and it is faster, too. Spencer Platt/Getty Images |

Muscles keep the action localized

Muscle tissue also tends to keep vaccine reactions localized. Injecting a vaccine into the deltoid muscle may result in local inflammation or soreness at the injection site.

If certain vaccines are injected into fat tissue, the chance of irritation and inflammation reaction increases because fat tissue has poor blood supply, leading to poor absorption of some vaccine components.

Vaccines that include the use of adjuvants – or components that enhance the immune response to the antigen – must be given in a muscle to avoid widespread irritation and inflammation. Adjuvants act in a variety of ways to stimulate a stronger immune response.

Yet another deciding factor in vaccine administration location is the size of the muscle. Adults and children ages three and older tend to receive vaccines in their upper arm in the deltoid. Younger children receive their vaccines mid-thigh because their arm muscles are smaller and less developed.

Another consideration during vaccine administration is convenience and patient acceptability. Can you imagine taking down your pants at a mass vaccination clinic? Rolling up your sleeve is way easier and more preferred.

Infectious disease outbreaks, as in flu season or amid epidemics like COVID-19, require our public health system to vaccinate as many people as possible in a short time. For these reasons, a shot in the arm is preferred simply because the upper arm is easily accessible.

All things considered, when it comes to the flu shot and the COVID-19 vaccine, for most adults and kids, the arm is the preferred vaccination route.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Libby Richards, Associate Professor of Nursing, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.