And maybe already has

Scott Shackelford, Indiana University

|

| For cybersecurity, your best bet is to assume that the enemy has already slipped inside. clu/DigitalVision Vectors via Getty Images |

This raises a couple of questions. What is zero-trust security? And, if trust is bad for cybersecurity, why do most organizations in government and the private sector do it?

One consequence of too much trust online is the ransomware epidemic, a growing global problem that affects organizations large and small.

High-profile breaches such as the one experienced by the Colonial Pipeline are merely the tip of the iceberg.

There were at least 2,354 ransomware attacks on local governments, health care facilities and schools in the U.S. last year. Although estimates vary, losses to ransomware seem to have tripled in 2020 to more than US$300,000 per incident. And ransomware attacks are growing more sophisticated.

A recurring theme in many of these breaches is misplaced trust – in vendors, employees, software and hardware. As a scholar of cybersecurity policy with a recent report on this topic, I have been interested in questions of trust. I’m also the executive director of the Ostrom Workshop. The Workshop’s Program on Cybersecurity and Internet Governance focuses on many of the tenets of zero-trust security by looking to analogies – including public health and sustainable development – to build resilience in distributed systems.

Security without trust

Trust in the context of computer networks refers to systems that allow people or other computers access with little or no verification of who they are and whether they are authorized to have access. Zero Trust is a security model that takes for granted that threats are omnipresent inside and outside networks.

Zero trust instead relies on continuous verification via information from multiple sources. In doing so, this approach assumes the inevitability of a data breach. Instead of focusing exclusively on preventing breaches, zero-trust security ensures instead that damage is limited, and that the system is resilient and can quickly recover.

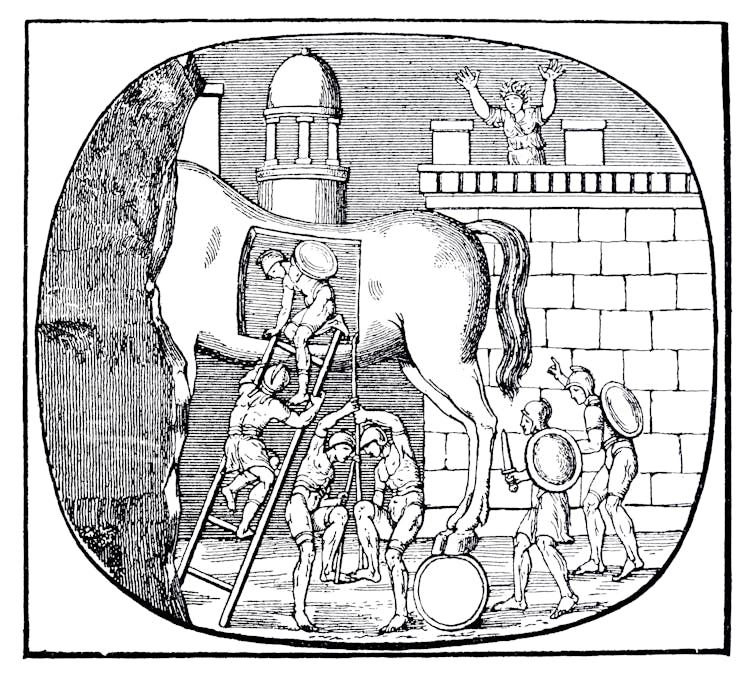

Using the public health analogy, a zero-trust approach to cybersecurity assumes that an infection is only a cough – or, in this case, a click – away, and focuses on building an immune system capable of dealing with whatever novel virus may come along. Put another way, instead of defending a castle, this model assumes that the invaders are already inside the walls.

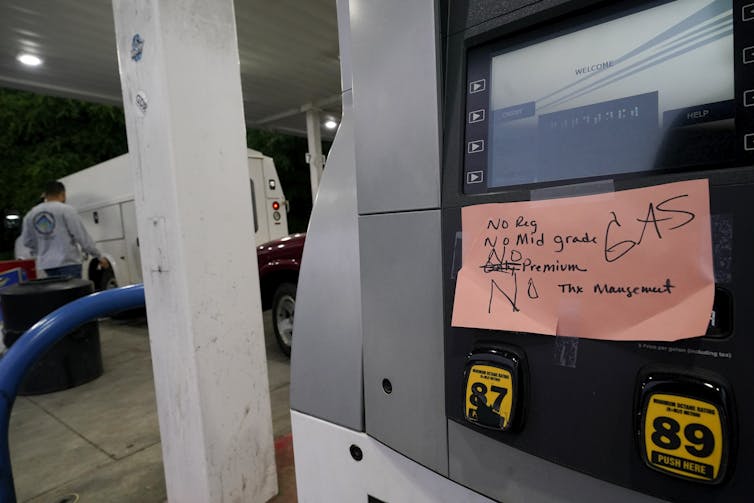

It’s not hard to see the benefits of the zero-trust model. If the Colonial Pipeline company had adopted it, for example, the ransomware attack would likely have failed and people wouldn’t have been panic-buying gasoline in recent days. And if zero-trust security were widespread, the ransomware epidemic would be a lot less biting.

|

| Widespread adoption of zero-trust security would minimize episodes like the panic-buying of gasoline in response to the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack. AP Photo/Chris Carlson |

Four obstacles to shedding trust

But there are at least four main barriers to achieving zero trust in government and private computer systems.

First, legacy systems and infrastructure are often impossible to upgrade to become zero-trust. Achieving zero-trust security requires a layered defense, which involves building multiple layers of security, not unlike a stack of Swiss cheese.

But this is challenging in systems that were not built with this goal in mind, because it requires independent verification at every layer.

Second, even if it’s possible to upgrade, it’s going to cost you. It is costly, time-consuming and potentially disruptive to redesign and redeploy systems, especially if they are custom-made. The U.S. Department of Defense alone operates more than 15,000 networks in 4,000 installations spread across 88 countries.

Third, peer-to-peer technologies, like computers running Windows 10 on a local network, run counter to zero trust because they rely mostly on passwords, not real-time, multifactor authentication.

Passwords can be cracked by computers rapidly checking many possible passwords – brute-force attacks – whereas real-time, multifactor authentication requires passwords and one or more additional forms of verification, typically a code sent by email or text. Google recently announced its decision to mandate multifactor authentication for all its users.

Fourth, migrating an organization’s information systems from in-house computers to cloud services can boost zero trust, but only if it’s done right. This calls for creating new applications in the cloud rather than simply moving existing applications into the cloud. But organizations have to know to plan for zero-trust security when moving to the cloud. The 2018 DoD Cloud Strategy, for example, does not even reference “zero trust.”

Enter the Biden administration

The Biden administration’s executive order attempts to foster a layered defense to address the nation’s cybersecurity woes. The executive order followed several recommendations from the 2020 Cyberspace Solarium Commission, a commission formed by Congress to develop a strategic approach to defending the U.S. in cyberspace.

Among other things, it builds from zero-trust frameworks propounded by the National Institute for Standards and Technology. It also taps the Department of Homeland Security to take the lead on implementing these zero-trust techniques, including in its cloud-based programs.

I believe that when coupled with other initiatives spelled out in the executive order – such as creating a Cybersecurity Safety Board and imposing new requirements for software supply chain security for federal vendors – zero-trust security takes the U.S. in the right direction.

However, the executive order applies only to government systems. It wouldn’t have stopped the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack, for instance. Getting the country as a whole on a more secure footing requires helping the private sector adopt these security practices, and that will require action from Congress.

[Over 106,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]![]()

Scott Shackelford, Associate Professor of Business Law and Ethics; Executive Director, Ostrom Workshop; Cybersecurity Program Chair, IU-Bloomington, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.