We should be able to teach and discuss the good and the bad about American history

|

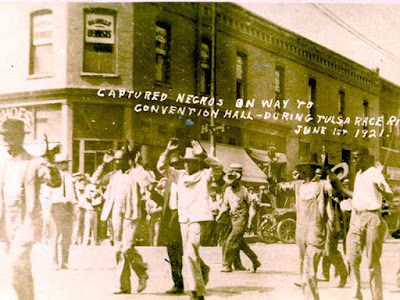

| Before this week, how many Americans knew about the 1921 Tulsa OK massacre? |

I’d like to set aside the fact that

the people most upset about critical race theory generally don’t understand what it is: a decades-old academic theory of how race and the

law have interacted in U.S. history, most often taught in law or graduate

schools.

Instead, I’d like to show just how

absurd these bills can be.

I teach about race at the college

level. In many cases, these bills ban what Republicans think we are teaching — e.g. that white people

should “feel guilty” for being white — not what we are actually teaching.

In other cases, they oppose

accurately teaching any negative part of U.S. history. North Carolina’s bill, for instance, says that schools

cannot promote “the belief that the United States… was created by members of a

particular race or sex to oppress members of another race or sex.”

Is that what I teach? Yes and no.

Yes, this country was founded by white men (we do refer

to them as founding fathers) who gave themselves rights they denied women and people of color.

Women couldn’t vote. Black people were enslaved. That’s our history.

But was that the reason the founding fathers created this country?

I am certain George Washington and Thomas Jefferson did not want independence from Great Britain purely to oppress women and people of color — they could have accomplished that comfortably as part of the British empire. Slavery was legal in Great Britain until 1833. Years later, the mom in Mary Poppins still was not allowed to vote, so she had to sing about it.

This aversion to teaching U.S.

history accurately seems to come from the idea that we can either believe that

the U.S. is perfect and has always been perfect or else it is no good at all.

But the truth is seldom all good or all bad — it is complex.

Take ancient Greece as an example.

The same society invented democracy and practiced

infanticide. Modern Americans would unanimously condemn the latter,

but does that mean we also cannot appreciate the former? Of course not.

We can let the Greeks be complex,

appreciating all of the good they gave the world, while acknowledging we would

not like to emulate many parts of their civilization. We can understand that

they were behaving in ways that were accepted in their time and we can simultaneously be completely horrified

by it. We can do the same for ourselves.

Looking at our own history, we can

see that the Europeans who came here developed an improvement over the

political systems of their home continent. Great Britain had begun its shift

toward parliamentary rule but, as of 1780, fewer than 3 percent of the population could vote.

However, nobody can take in the full

scope of U.S. history and find no evidence of racism or sexism. We all know

that. In addition to slavery, formal racial segregation was legal until the

1960s. And marital rape was legal in some states until 1994.

There’s more that many Americans

don’t know. In the 1800s, the U.S. government paid bounties to people who murdered Native Americans.

Think about that. Murder was not just legal but also encouraged and

compensated.

The question opponents of critical

race theory don’t want us to ask is: How did the past affect the present? What

parts of the ugly side of our history have we retained, even unintentionally?

Understanding these lessons is the whole point of studying history.

We do a disservice to our own

history if we do not study all of it, in all of its complexity, in order to

secure a better future.

OtherWords columnist Jill Richardson is pursuing a PhD in sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This op-ed was distributed by OtherWords.org.