Free speech can be crude

Nancy Costello, Michigan State University

|

| A Supreme Court ruling on free speech does nothing about toxic online discourse. Francesco Carta fotografo/Moment via Getty Images |

In 2017, high school sophomore Brandi Levy tried out for and failed to make the varsity cheerleading squad at Mahanoy Area High School in Pennsylvania. She made the junior varsity team instead.

The angry 14-year-old turned to social media to vent her frustration. She posted to Snapchat a photo of herself with a middle finger raised and a caption that read, “F— school, f— softball, f— cheer, f— everything.”

She posted the message online on a weekend, not during the cheerleading season, while hanging out with a friend at a convenience store. A screenshot of the self-deleting message was shown to school officials, who suspended Levy from cheerleading for the next year.

Claiming their daughter’s First Amendment free-speech rights had been violated, Levy’s parents sued the school district.

Hailed as the most significant case involving free-speech rights of students to be reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 50 years, it ended with court ruling that Levy’s First Amendment rights had been violated, though justices also said there were other circumstances in which the school could punish students for things they say off-campus.

Civic engagement or rhetorical weapon?

As a First Amendment expert, I see this ruling as a victory for First Amendment rights. But as a citizen and teacher troubled by the demise of civil discourse in the U.S., I am aware that the court’s ruling does nothing about the growing problem of ill-mannered, even toxic speech – by students and adults. The problem runs much deeper than posting F-bombs online.

Many Americans use the First Amendment not as a tool of civic engagement but as a weapon to avoid consequences for voicing hateful, repulsive or profane expression. At a time when most young Americans prefer to communicate by text or social media, rather than face-to-face interaction, civil discourse is withering.

But it is not the role of the Supreme Court to prescribe civility – or ban incivility. That’s up to us, and I believe it’s clear that Americans need to know more about the First Amendment, and practice in-person interaction, to properly understand how free speech can be a productive part of civil discourse.

Free speech is complex

In a 2018 Knight Foundation survey of almost 10,000 high school students, 89% supported the right to express unpopular opinions; however, only 45% believed people have the right to express speech that others considered offensive. A survey of college-age students produced similar results.

Some commentators have suggested these contradictory results show there is a philosophical conflict in balancing free-speech protections with a respect for diversity and inclusion.

But something else could be true: Young people – and Americans as a whole, of all ages – simply may not understand First Amendment free-speech rights.

The First Amendment protects a broad spectrum of speech, even speech that offends and makes people feel uncomfortable, because a thriving democracy depends on cultivating a vigorous marketplace of ideas. Citizens should ponder and sift the merits and pitfalls of diverse ideas to make good public policy.

In a 2018 survey by the Freedom Forum Institute, a nonprofit advocacy group promoting the First Amendment, 40% of adults interviewed could not name even one right guaranteed by the First Amendment. By 2019, that number dropped to 29%, but still that’s about 1 in 3 Americans who don’t know the first thing about the First Amendment.

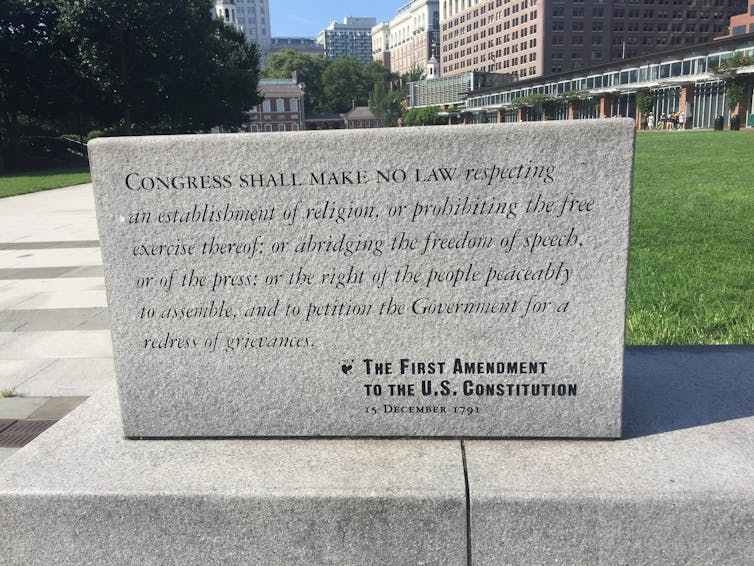

|

| A stone monument to the First Amendment, outside Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Zakarie Faibis via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA |

As knowledge about the First Amendment has waned, so has training in this fundamental constitutional right.

In 2006, 72% of high school students surveyed by the Knight Foundation reported having taken a class that studied the First Amendment. But 12 years later, in 2018, that percentage had dropped to 64%.

Coupled with a decline in young people’s knowledge about free-speech rights comes a decline in their interest in face-to-face verbal communication.

In 2012, 49% of teenagers preferred talking in person, with 42% preferring texting or other tech-driven communication. And 34% were on social media multiple times a day. By 2018, though, 61% of teenagers surveyed preferred texting or using social media to talking in person. And 70% were on social media more than once a day, with 16% saying they use social media “almost constantly.”

I expect that after a year of pandemic-related separation and isolation, even more teens will feel more comfortable with digital communication and less interested in in-person conversations. The result? Teenagers who mature into adults are less interested in, and less adept at, the primary form of communication for the human species – talking face to face.

In-person interaction is key

The seemingly random, aimless conversations teens can have while strolling through a shopping center, while gaming together or over a burger actually serve an extremely important role. It is in the real-time conversational experience that people learn whether something they say is well received or offensive.

When speaking in person, they can read a friend’s facial expression, body language and emotions and think to themselves, “Uh-oh, maybe I shouldn’t have said that, or said it differently. Instead, I should have said ….”

As young people mature, most learn through this process to say things less bluntly, less dismissively and with more mutual respect. Face-to-face conversation cultivates reflection and, with practice, the art of civil discourse.

|

| Spending time together in person helps everyone learn to moderate their self-expression and improves mutual understanding, even through disagreements. ferrantraite/E+ via Getty Images |

Fostering real exchange

But when 70% of teenagers are primarily engaging with other people and the world online, it is easy for them to impulsively send words and images into the ether, never knowing how bluntly or cruelly their messages strike others.

Social media is a good place for personal boasting and passing judgment, but it makes us worse at listening and doesn’t help develop humility, both key elements of productive civil discourse.

Is it any wonder, then, when a teenager confronts an idea she doesn’t like the response is not “It’s interesting you feel that way, please explain” but rather, “You suck!” – end of story. Online there is not a person right in front of her with hurt feelings, providing the social – not legal – consequences of intemperate or even offensive speech.

In my own law school classroom, I have tried not only to teach students about free-speech principles but to give them opportunities to engage in respectful, face-to-face speech, even when they disagree. I paired a pro-Trump law student with a first-generation Middle Easterner to teach First Amendment workshops at a rural Michigan school.

The students didn’t change their political views, but the pro-Trump student learned about the fears of immigrants who faced threats of deportation by the Trump administration, despite their decades of hard work and contributions in America. The Middle Easterner put aside her bias and learned to work as a team to provide free-speech training to dozens of high school teenagers.

Similar student encounters are possible across schools’ and colleges’ curricula because free expression is involved in a myriad of subjects – English, art, psychology, theater and other disciplines.

Fostering diversity of thought in a culture that welcomes a robust exchange of ideas takes skill and practice, for young and old alike. No decree by the Supreme Court can do that for us.![]()

Nancy Costello, Associate Clinical Professor of Law, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[Understand what’s going on in Washington. Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]