Indexing Rhode Island’s Indigenous history

Brown University

|

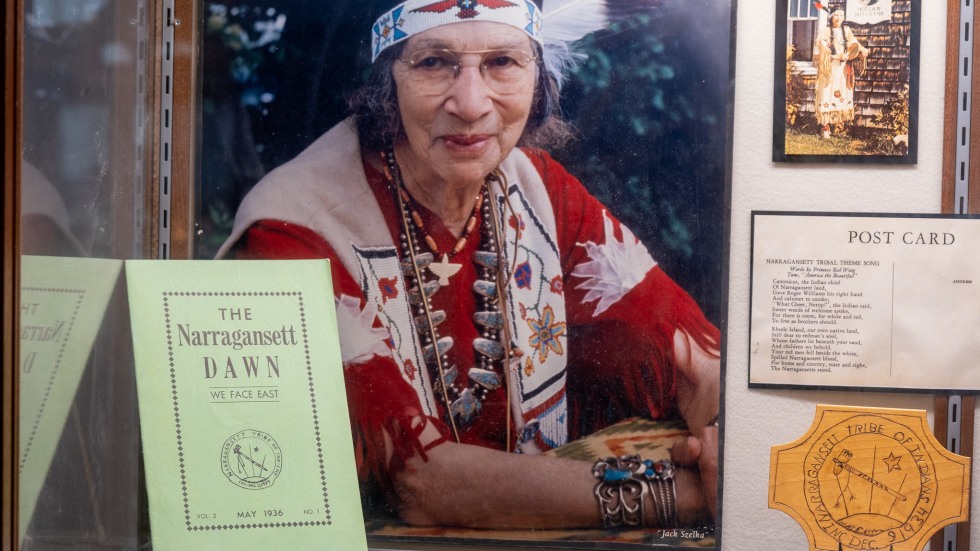

| The Dawn was edited by Princess Red Wing, a Narragansett and Wampanoag elder and historian, and Ernest Hazard, a member of the Narragansett Tribe. |

For nearly a century, issues of the Narragansett Dawn — a monthly magazine containing valuable historical information and unique insights into 20th-century Native American life — have been hiding in plain sight.

Most issues of the Dawn, published by two members of the Narragansett Tribe in 1935 and 1936, are available on the University of Rhode Island’s digital commons website — but they are without critical metadata that help scholars find information with search terms and keywords. Others sit in boxes, waiting to be digitized, in the archive of the Tomaquag Museum, an Indigenous history, culture and arts museum in Exeter, Rhode Island.

This summer, Halle Bryant, a Class of 2021 Brown graduate, is working with Tomaquag Museum staff to bring the Dawn’s important contents out of the shadows.

“It seems like the Dawn originated as a way for members of the Narragansett tribal community to connect and stay up to date,” Bryant said.

“But you can see that over the course of two years, it quickly grew to include regular columns and insight from Native Americans across New England and the country. It speaks not only to the history, traditions, food practices and news of the Narragansett Tribe but also to the larger story of Native American dispossession and Native Americans’ relationship with the natural environment, which is really valuable.”

Bryant, who earned a dual degree in applied math and Africana studies in May, is spending her first post-graduation summer reading and indexing every issue of the periodical, which each month collected news, stories and poetry by, for and about Native Americans in Rhode Island and beyond.

An early edition read: “The Narragansett Dawn is the speaking leaves of the tribe... Here you will find our work, our pleasures, our social activities, our life, history, traditions, signs and tongue.”

By the end of the summer, Bryant will have read every word of every issue of the Dawn, and she’ll have created a comprehensive catalog of names, dates and places mentioned in the text, as well as related themes and keywords.

Ultimately, her work will make it easier for students, faculty and the general public to find and cite information contained in the publication, deepening scholarly and public understanding of Native American history and everyday life.

“There’s so much knowledge contained in these archives, and there’s so much research that could be done with it, that it’s almost overwhelming to think about,” Bryant said. “At the end of the summer, I will be one of only a few living people who have read every issue. But hopefully that will change as more people become aware of this resource and gain access to it.”

A window into the maritime past

|

| Some back issues of the Dawn are only available to view in person in the Tomaquag Museum's archives, managed by Anthony Belz, pictured here with Bryant. |

Funded by a $4.9 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the project uses maritime history as a basis for studying the relationship between European colonization, dispossession of Native American land and racial slavery in the United States.

The Dawn repeatedly highlights the Narragansett Tribe’s close relationship with Rhode Island’s waterways and describes the ways in which that relationship changed following European colonization.

An August 1935 piece detailed how European colonization along the Pettaquamscutt River and Narragansett Bay drove tribal members inland, transforming them from year-round wanderers to part-time settlers. A 1936 edition included an obituary of Samuel Mingo, who was born on Narragansett lands and later became famous for his round-the-world whaling expeditions.

The opening lines of an early edition, penned by Narragansett and Wampanoag elder and historian Princess Red Wing, read, “Come with me for two minutes, to the banks of the Narragansett Bay, to the home of my ancestors long before the white men came.”

Thanks to Bryant’s indexing work, much of the Dawn’s history and news could soon make its way into scholarship by Brown University and Williams College researchers and exhibits at the Tomaquag and Mystic Seaport museums. But the work’s value will endure beyond the immediate future, said Lorén Spears, executive director of the Tomaquag Museum.

“There is a vast quantity of historical 19th- and 20th-century knowledge encapsulated in the Narragansett Dawn,” Spears said. “It speaks to the conquest, colonization, wars, intergenerational trauma and survivance of our people. The work that Halle is doing will create an index of all the people, places, events, dates, cultural knowledge and key topics highlighted, giving more scholars, authors, artists, filmmakers and other lay researchers the opportunity to use this irreplaceable resource. It will also allow our own staff to utilize it more efficiently in creating educational programs, curricula and exhibits.”

According to Spears, the Dawn brought Indigenous stories and perspectives to the fore at a time when Native American history was at best ignored and at worst deliberately erased from the public record.

In 1880, the Rhode Island legislature passed a “detribalization” law that essentially ended support for the Narragansett Tribe in part by denying tribal members’ claims to ancestral land in Washington County.

By the 1930s, local Native American history had faded into such obscurity that white Rhode Islanders were hosting “Victorian teas” at a site where, unbeknownst to them, colonial militiamen had massacred hundreds of Narragansett men, women and children 250 years earlier.

Princess Red Wing used the Dawn to advocate for the state to erect a monument at the site, now understood to be one of the bloodiest conflicts per capita in U.S. history.

“This publication created a visibility and a documentation of what the Narragansett and other Southern New England communities were doing at that time,” Spears said. “It was reflecting on what happened in our past and sharing our goals for the future.”

I’m grateful to my professors in the Africana studies department for the real care they put into shaping our growth into full people, not just as students. Because of what I’ve learned from them, I know how to think about the implications of what I’m doing. That will always help me act with intention.

Participating in a larger research project that connects Native American dispossession and racial slavery is personally meaningful to Bryant, who grew up in South Orange, New Jersey, to parents with African and Tuscarora ancestry.

“Being part of this research group has cemented for me that you can’t separate the histories of Black Americans and Native Americans,” Bryant said.

|

| HALLE BRYANT Class of 2021 |

Those intertwined histories came alive to Bryant both inside and outside the classroom while she was at Brown. Courses she took that touched on the relationships between African and Native American history included Introduction to Africana Studies, Global Black Radicalism and American Slavery. And in her junior year, she learned more about both African and Indigenous slavery in the Caribbean while conducting historical research for an upcoming PBS documentary on the trans-Atlantic slave trade, part of another CSSJ research project.

In the fall, Bryant will move on to a job as a trust and safety analyst at Discord, helping to prevent the spread of extremist rhetoric and sexual harassment on the popular messaging platform. She hopes to spend time later in life teaching children. Though she doesn’t know precisely what the far-flung future holds professionally, she said that she’s prepared to tackle any number of scenarios, thanks to her Brown education.

“I want to make myself useful, and right now I’m just seeing what feels right,” Bryant said. “I’m grateful to my professors in the Africana studies department for the real care they put into shaping our growth into full people, not just as students. Because of what I’ve learned from them, I know how to think about the implications of what I’m doing. That will always help me act with intention.”