Space Lasers Map Meltwater Lakes

NASA

|

| June 9 - September 7, 2019 |

|

| Wingnut Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene came up with the theory that California's forest fires are being caused by secret "Jewish Space Lasers" |

At its thickest points, Antarctic ice can be hundreds to thousands of meters thick; the rising and falling caused by meltwater lakes tends to be subtle and localized.

But with

ICESat-2, scientists can map even small ice elevation changes with a precision

down to just a few centimeters.

“These are processes going on under Antarctica that we wouldn’t have a clue about if we didn’t have satellite data,” said Helen Amanda Fricker, a glaciologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “We’ve been struggling with getting good predictions about the future of Antarctica, and instruments like ICESat-2 are helping us observe at the process scale.”

In one study,

glaciologist Roland Warner,

Fricker, and colleagues used data from ICESat-2 and Landsat 8 to chronicle the

abrupt collapse of a large, ice-covered lake on top of

the Amery Ice Shelf in

2019. A fracture opened on top of the ice shelf and drained water to the ocean

cavity below, leaving behind a crater (known as a doline) about 10 square

kilometers (4 square miles) across the surface. Within three days, the fracture

funneled nearly 200 billion gallons of freshwater from the ice surface into the

ocean off of East Antarctica.

During the summer,

thousands of turquoise meltwater lakes dot the surface of Antarctica’s ice

shelves. But the 2019 drainage event occurred in the middle of austral winter,

when scientists expect water on the surface to be completely frozen. Warner

first spotted the scarred ice shelf in images from Landsat 8, then turned to

Fricker and colleagues who work with ICESat-2.

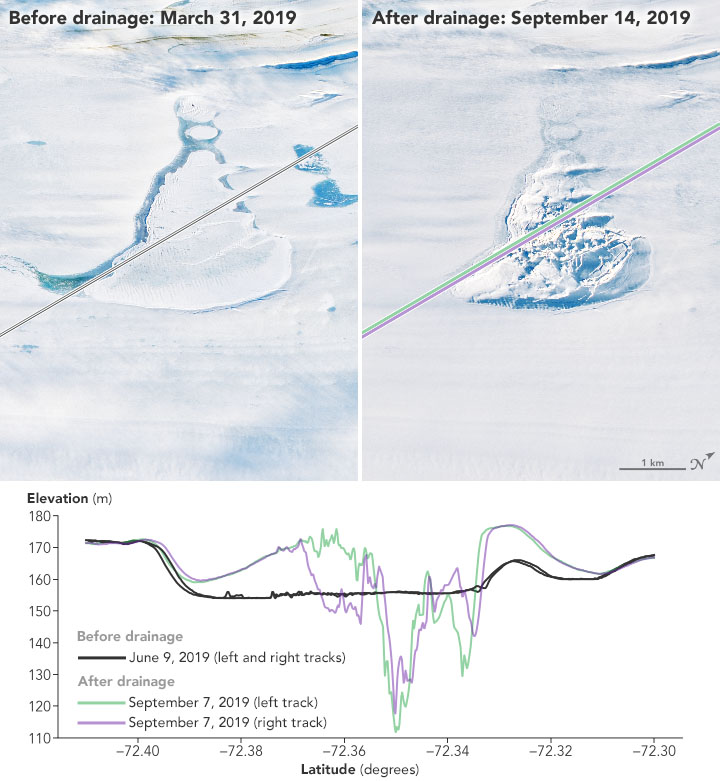

The images above capture changes in the surface of the Amery Ice Shelf between March and September 2019. The two natural-color images were acquired by the Operational Land Imager on Landsat 8.

The lines across each scene show the tracks of laser signals sent and received by the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System (ATLAS) on ICESat-2 in June and September 2019. ATLAS is a photon-counting lidar that sends pulses of laser light toward Earth and precisely times each photon’s round-trip journey as it bounces off a surface and returns to the sensor.

From

this information scientists can derive the height of the ice surface hit by the

photon. Note how the ice surface dropped in some places and flexed upward in

others after the lake drained.

“Because of the loss of

this weight of water on the surface of the floating ice shelf, the whole thing

bends upwards centered on the lake,” said Warner, a scientist at the University

of Tasmania and lead author of the study. “That’s something that would have

been difficult to figure out just staring at satellite imagery.”

The drainage event was most likely caused by a hydrofracturing process in which the mass of the lake’s water led to a surface crack being driven through the ice shelf to the ocean below.

Because meltwater lakes and streams are common during warmer months—and scientists expect them to become more common as global temperatures continue to rise—the risk of hydrofracturing could increase in coming decades.

Still, the

research team said it is too early to determine whether a warming climate

caused the demise of the lake on Amery Ice Shelf.

Witnessing the formation of a doline with altimetry data was a rare opportunity, but it is also the type of event glaciologists need to analyze in order to account for all of the ice dynamics that are relevant in models of Antarctica.

The observations are

important for assessing how such hidden plumbing systems influence the speed at

which ice slips into the Southern Ocean. Melting and calving ice adds

freshwater that may alter ocean circulation and ecosystems.

Lakes also form under the massive Antarctic ice sheets, and when they gain or lose water, they can deform the frozen surface above.

In a related study integrating data from ICESat-2, the original ICESat mission, and the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2, Fricker and geophysicist Matthew Siegfried showed that a group of lakes in West Antarctica—including the Conway and Mercer lakes under the Mercer and Whillans ice streams—are draining for the third time since the original ICESat began making measurements in 2003.

They also discovered two new

lakes in this region, while revealing that the outlines or boundaries of

subglacial lakes can change gradually as water enters and leaves the

reservoirs.

“ICESat-2 is like

putting on your glasses after using ICESat,” said Siegfried,

a researcher at the Colorado School of Mines. “We are mapping out any height

anomalies that exist at this point. The data are such high precision that we

can really start to map out the lake boundaries on the surface. If there are

lakes filling and draining, we will detect them with ICESat-2.”

NASA Earth Observatory

image by Joshua Stevens,

using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological

Survey and data courtesy of Warner, R.C., et

al. (2021). Story by Roberto Molar Candanosa, NASA’s Earth Science

News Team, with Mike Carlowicz.