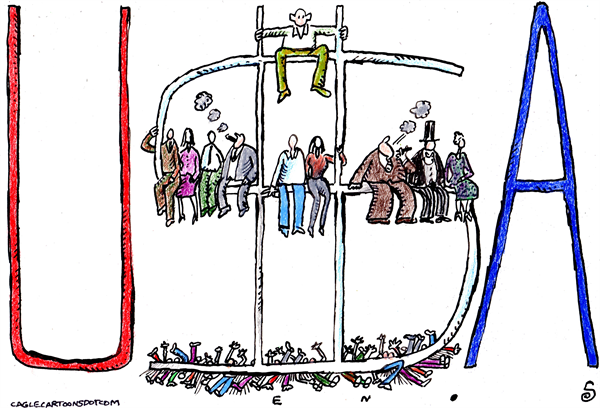

Why So Much Wealth at the Top Threatens the US Economy

By Robert Reich

Policymakers and the media are paying too much attention to how quickly the U.S. economy will emerge from the pandemic-induced recession, and not nearly enough to the nation’s deeper structural problem – the increasing imbalance of wealth that could enfeeble the economy for years.

Seventy

percent of the US economy depends on consumer spending. But wealthy people, who

now own more of the economy than at any time since the 1920s, spend only a

small percentage of their incomes. Lower-income people, who were in trouble

even before the pandemic, spend whatever they have – which has become very

little.

In

a very practical sense, the U.S. economy depends on the spending of most

Americans who don’t have much to spend. That spells trouble ahead.

It’s

not simply a matter of an adequate “stimulus.” The $2,000 checks contained in

the American Rescue Plan have already been distributed and extra unemployment

benefits will soon expire. Consumer spending will be propped up as employers

add to their payrolls. Biden’s spending plans, if enacted, will also help keep

consumers afloat for a time.

But

the underlying imbalance will remain. Most peoples’ wages will still be too low

and too much of the economy’s gains will continue to accumulate at the top, for

total consumer demand to be adequate.

Years ago, Marriner Eccles, chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1934 to 1948, explained that the Great Depression occurred because the buying power of Americans fell far short of what the economy could produce. He blamed the increasing concentration of wealth at the top. In his words:

“A giant suction pump had by 1929-1930 drawn into a few hands an increasing portion of currently produced wealth. As in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped.”

The

wealthy of the 1920s didn’t know what to do with all their money, while most

Americans could maintain their standard of living only by going into debt. When

that debt bubble burst, the economy sunk.

History

is repeating itself. The typical Americans’ wages have hardly increased for

decades, adjusted for inflation. Most economic gains have gone to the top, just

as Eccles’s “giant suction pump” drew an increasing portion of the nation’s wealth

into a few hands before the Great Depression.

The

result has been consumer spending financed by borrowing, creating chronic

fragility. After the housing and financial bubbles burst in 2008, we avoided

another Great Depression only because the government pumped enough money into

the system to maintain demand, and the Fed kept interest rates near zero. Then

came the pandemic.

The

wealth imbalance is now more extreme than it’s been in over a century. There’s

so much wealth at the top that the prices of luxury items of all kinds are

soaring; so-called “non-fungible tokens,” ranging from art and music to tacos

and toilet paper, are selling like 17th-century exotic Dutch tulips; cryptocurrencies have taken off;

and stock market values have continued to rise even through the pandemic.

Corporations

don’t know what to do with all their cash. Trillions of dollars are sitting

idle on their balance sheets. The biggest firms have been feasting off the

Fed’s corporate welfare, as the central bank obligingly holds corporate bonds

that the firms issued before the recession in order finance stock buybacks.

But most people

have few if any assets. Even by 2018, when the economy appeared strong, 40% of Americans had negative net incomes and were

borrowing money to pay for basic household needs.

The

heart of the imbalance is America’s wealthy and the corporations they own have

huge bargaining power – both market power in the form of monopolies, and

political power in the form of lobbyists and campaign contributions.

Most

workers have little or no bargaining power – neither inside their firms because

of the near-disappearance of labor unions, nor in politics because political

parties have devolved from giant membership organizations to fundraising

machines.

Biden’s

“stimulus” programs are fine but temporary. The most important economic reform

would be to correct this structural imbalance by reducing monopoly power,

strengthening unions, and getting big money out of politics.

Until

the structural imbalance is remedied, the American economy will remain

perilously fragile. It will also be vulnerable to the next demagogue wielding

anger and resentment as substitutes for real reform.

Robert Reich's latest book is "THE SYSTEM: Who Rigged

It, How To Fix It." He is Chancellor's Professor of Public Policy at the

University of California at Berkeley and Senior Fellow at the Blum Center. He

served as Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration, for which Time

Magazine named him one of the 10 most effective cabinet secretaries of the

twentieth century. He has written 17 other books, including the best sellers

"Aftershock," "The Work of Nations," "Beyond

Outrage," and "The Common Good." He is a founding editor of the

American Prospect magazine, founder of Inequality Media, a member of the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and co-creator of the award-winning

documentaries "Inequality For All," streaming on YouTube, and

"Saving Capitalism," now streaming on Netflix.