Wildfire Smoke in New England Is “Pretty Severe from Public Health Perspective”

KAT J. MCALPINE in Boston University's The Brink

On

Monday, the air quality in Boston and the greater New England area was so bad that it was only rivaled by the areas in Northern

California and Oregon currently on fire.

Credit: Emily Chaf, Wayland Student Press

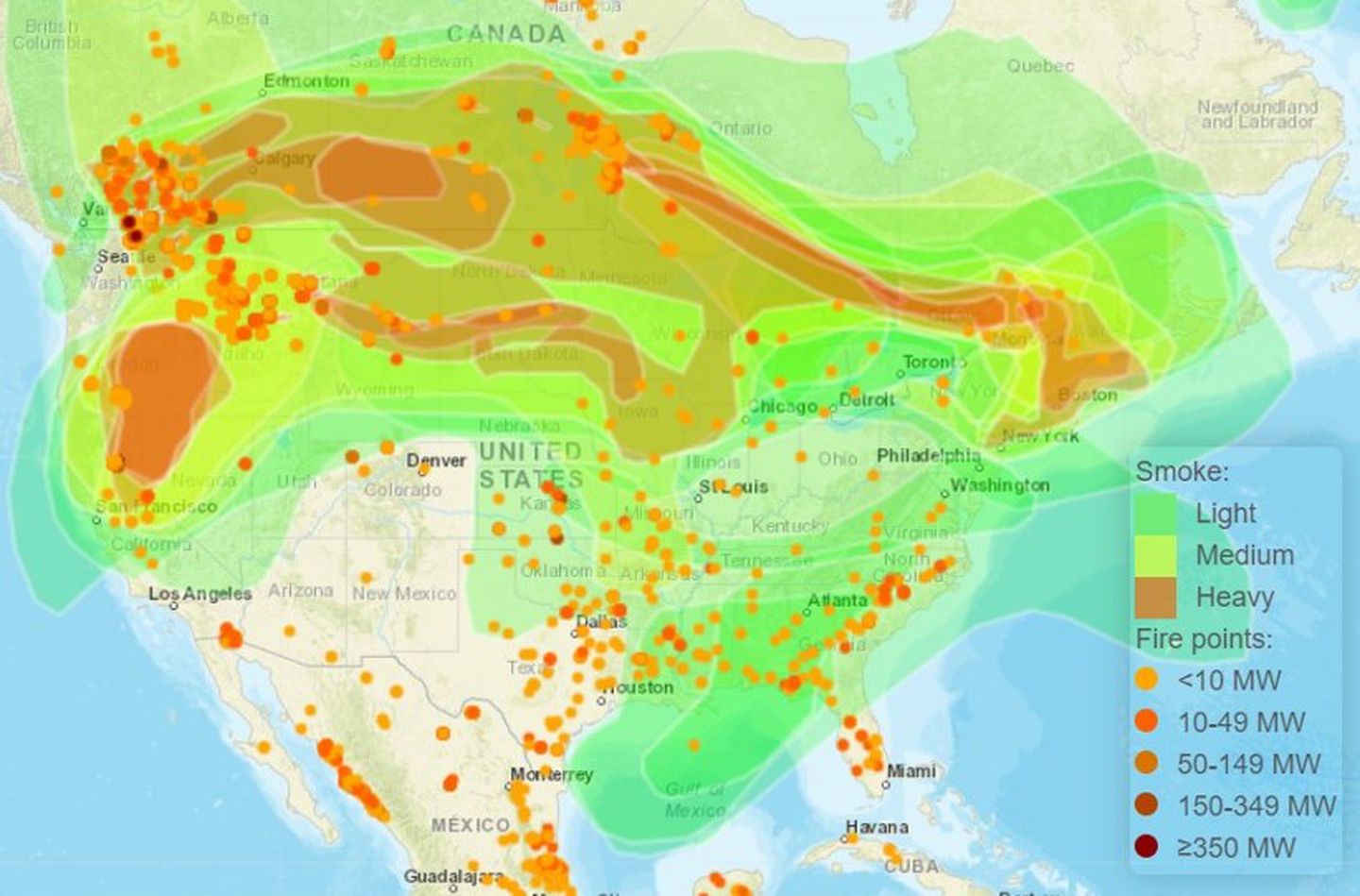

An interactive map from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration showed how smoke from the wildfires out west were being carried across the continental US by winds and the jet stream.

In response to the blanket of smoke engulfing the

commonwealth’s skies, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental

Protection issued an air quality alert.

Around

Boston, people reported not only seeing a film of smoke in the skies, but also

smelling the scent of wood burning. Firefighters across the state fielded calls

from concerned residents who worried that a fire was burning nearby. This is

the second time in the last two weeks that smoke from the western forest fires

has been carried to New England—but the smoke was markedly thicker and more

pungent this time around.

With scientists predicting that our climate will continue to get hotter and drier, exacerbating normal patterns of forest fires, The Brink reached out to Boston University environmental earth scientist Mark Friedl for help understanding what these changes mean for our planet and for human health.

Friedl, an expert in using NASA satellite imaging to interpret large-scale environmental trends, recently published new research findings indicating that forest fires in Earth’s northernmost forests could accelerate climate change—potentially locking the planet in a feedback loop where drier climate causes more fires and those fires, in turn, speed up global warming.

“Fires are intensifying, and when forests burn, carbon

is released into the atmosphere,” Friedl says about those findings.

Friedl, a BU College of Arts & Sciences professor of earth and environment and interim director of BU’s Center for Remote Sensing, answers four questions posed by The Brink about the effects of western wildfire smoke over New England and the US.

An interactive map from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) shows the smoke from the wildfires in the Western US and Canada being carried across the country. Map courtesy of the NOAA

The

Brink: Based

on your research and expertise in remote global sensing and monitoring, what do

these current wildfires tell us about where Earth’s climate is going?

Friedl: These

fires are further evidence of how climate change is impacting ecosystems and

forests. Fire is normal in forested ecosystems, especially in western forests

that tend to be drier, and hence more fire-prone, relative to forests in the

eastern US. That said, the increased frequency, intensity, and scale of

fires we’ve seen in recent years is a clear by-product of climate

change. They are the proverbial canary in the coal mine, telling us that

the climate is changing, and it’s going to increasingly impact our lives on a

day-to-day basis.

Does

this much smoke, spreading across the country, impact vegetation elsewhere

besides the forests that are burning?

Smoke

like we experienced today tends to be pretty short-lived and doesn’t have much

impact on vegetation across the country. Indeed, it’s not entirely unheard of

for smoke to travel long distances in the atmosphere, and it’s not

unprecedented for smoke from fires in the western US to make it all the way to the eastern US.

What

about the effects on human health?

Most

of the time, the smoke is diffuse and concentrated in the upper atmosphere, and

so we just experience it as haze. What we experienced [Monday], with very

poor air quality, is qualitatively different, and is pretty severe from a

public health perspective. Hopefully, this is not a harbinger of things to

come. It’s also worth noting that at least some of the smoke we see right

now is coming from fires in western and central Canada, and not just from the

western US.

With

wildfires becoming more common as the climate gets hotter and drier, what will

happen if fires burn faster than forests can replenish themselves? Can you

predict what the future dynamics look like in the West and Pacific Northwest

forests?

If

the climate continues to warm and becomes drier in the west, at some point some

forests will not be able to recover. If there’s a silver lining in these fires,

it’s that hopefully they provide a wake-up call for society to change and start

to meaningfully address the climate crisis.

Kat J. McAlpine is editor of The Brink, Boston University’s news site for scientific breakthroughs and pioneering research. Kat has been telling science stories for over a decade, and prior to joining BU’s editorial staff, publicized research at Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and the University of Connecticut’s School of Engineering.