To advance human rights, consult neuroscience

Brown University

|

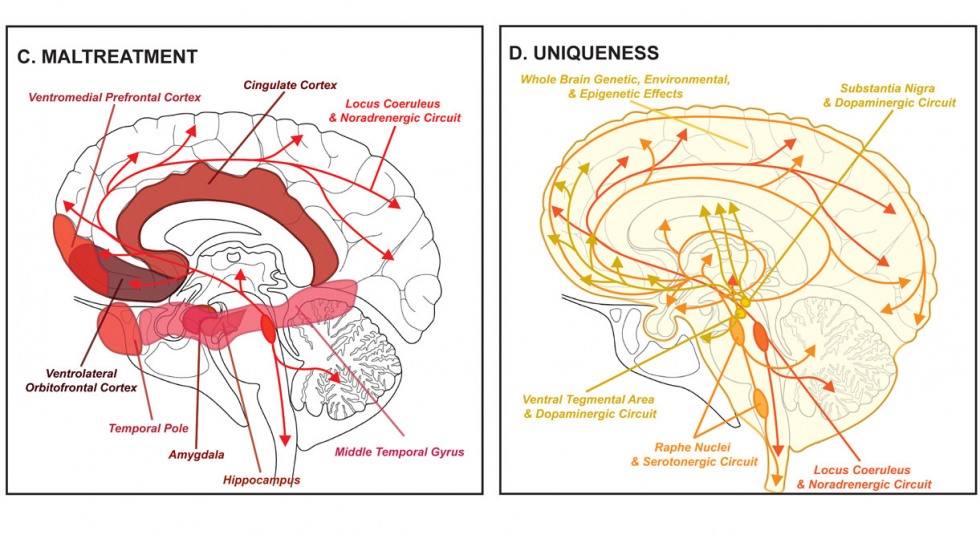

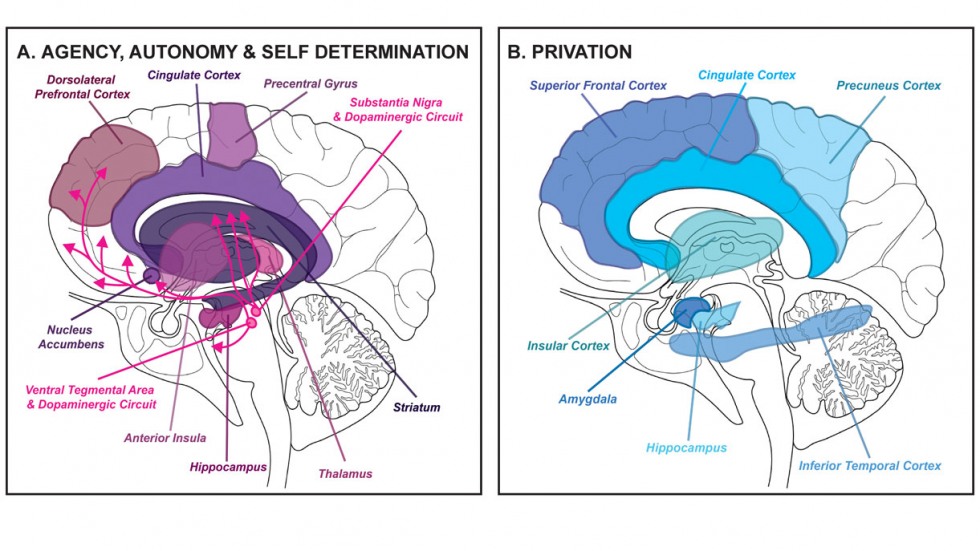

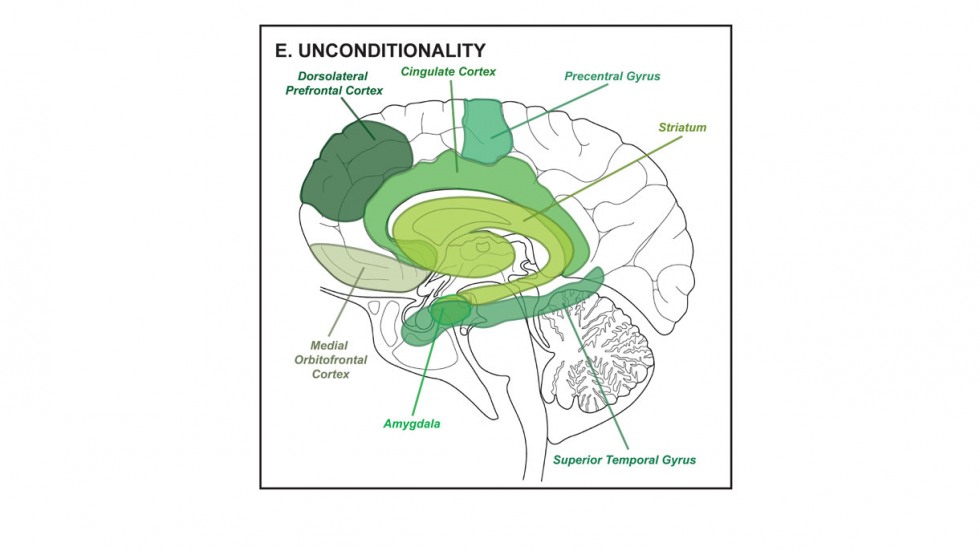

| White and Gonsalves created representations of the neural structures and circuits that support five major concepts underlying most universal rights declarations. |

The Code of Hammurabi. The Magna

Carta. The Declaration of Independence. Throughout recorded human history,

written records such as these have proclaimed that people deserve freedom,

security and dignity.

Why, despite huge cultural

differences across continents and sweeping societal changes across centuries,

have the underlying concepts in these declarations of rights remained largely

unchanged?

According to a pair of scientists at

Brown University, it’s because all humans share the same nervous system.

In a new scientific paper, the scholars introduce a new concept called “dignity neuroscience” — the idea that universal rights are rooted in human brain science.

The authors argue that numerous studies in disciplines such as developmental psychology and neuroscience bolster long-held notions that people thrive when they enjoy basic rights such as agency, self-determination, freedom from want or fear, and freedom of expression.

And they say science also supports the idea that when

societies fail to offer their citizens such rights, allowing them to fall into

poverty, privation, violence and war, there can be lasting neurological and

psychological consequences.

The paper was published on Thursday, Aug. 5, in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

Tara White, the paper’s lead author

and an assistant professor (research) of behavioral and social sciences at

Brown, said she believes grounding universal human rights in science could help

people see themselves in the sweeping statements of the 1948

Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“I think the average person on the

street sees universal human rights as an international law concept that has

more to do with trade than about individual lives,” White said. “But this stuff

is not pie-in-the-sky, and it affects us all. We want to show people that

ensuring universal human rights is a crucial foundation for a society that is

healthy — not only socially and physically, but also psychologically and

neurologically.”

|

| White and Gonsalves created representations of the neural structures and circuits that support five major concepts underlying most universal rights declarations. |

White — who is affiliated with Brown’s Carney Institute for Brain Science — and co-author Meghan Gonsalves, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at Brown, outlined five core concepts that underlie most universal rights declarations: agency, autonomy and self-determination; freedom from want; freedom from fear; uniqueness; and unconditionality. All five, they argue, reflect fundamental features of human brain structure, function and development.

For instance, multiple studies on learning and emotion have shown that gray matter in multiple regions of the brain helps people draw on their own memories to assess whether goals are worth pursuing or whether risks are worth taking.

Those studies demonstrate that

agency — the ability to shape one’s own choices and actions in the world

— is intrinsic to the brain. In addition, studies have shown that

observers, victims and combatants of war experience long-term brain trauma in

the form of heightened stress levels, negative emotions and fears of physical

danger, even after threats of violence have passed — adding scientific weight

to declarations that all people deserve to be shielded from war when possible.

“With this paper, we had an

opportunity to show that the idea of universal human rights as a foundation for

a healthy society isn’t just a social phenomenon but also a deeply empirical

and scientific one,” Gonsalves said. “Applying scientific studies and hard

evidence to universal human rights can help demonstrate why these rights need

to be defended and respected across the world.”

The idea of “dignity neuroscience” first emerged for White three years ago, when she was invited to a human rights conference in London while serving as a visiting international fellow at the British Academy and the University of Cambridge.

White was the only behavioral

neuroscientist in a room full of United Nations officials and international law

experts, and at first, she considered herself an outside observer rather than a

participant. As many in the room lamented an apparent global shift away from allegiance

to universal rights — an increasing number of leaders, they noted, were

sanctioning the free press, stripping away voting rights and modifying

democratic laws with impunity — White felt she had no advice to offer.

“Then the lightning bolt hit: Every single part of my training was relevant to these ideas,” White said.

“All of

the very complex international laws they were discussing fell into five

categories, and all of them had a basis in psychology and developmental

neuroscience. I stood up at the end of the conference and essentially outlined

my idea for this paper and asked, ‘Would this be helpful for your work?’ And

the speakers said, ‘Yes, we’ve never considered these ideas, we think they

might help.’”

In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic

ravaged all seven continents and Americans were locked in bitter division over

politics, racism and police violence, White felt that exploring the

intersection of neuroscience and universal rights had taken on added urgency.

Gonsalves agreed.

“I felt a certain fire in my belly to somehow respond to the pandemonium surrounding the election, inequalities that the pandemic was exacerbating, and increased violence against Black Americans,” Gonsalves said.

“I wanted to help others and build a better

society, and I think these ideas can do that. I believe the more we can use

science to communicate our commonalities and differences, the more successful

we will be in encouraging compassion.”

White said that while the paper

provides a comprehensive set of connections between universal rights law and

brain science, she hopes the work inspires more connection between people in

vastly different fields of study. Crossing traditionally siloed scientific

aisles could lead to breakthroughs for brain scientists, social scientists and

law experts alike.

Understanding and considering “dignity neuroscience” could also, White said, help lawmakers and voters appreciate the simultaneous importance of providing each person with the same basic rights while also giving them room to live as they please.

It’s true, she

said, that all human brains work in broadly similar ways; for example,

responding positively to others’ affirmations and negatively to trauma. But

brains are also plastic: They develop in response to the experiences they

endure and the surroundings they observe, adapting with each new experience and

change of scenery. Therefore, no two brains, and by extension no two humans,

are exactly alike.

“If I had one takeaway, it would be

this: People are worthy of respect because of who they are, because they are

the same as you and because they are different than you,”

White said. “We all have common needs, and when those needs are fulfilled, it

helps us flourish. But at the same time, each of us deserves space for agency,

because we are all unique.”

The research was supported by the

British Academy International Visiting Fellowship (BA #VF1-102524); the Clare

Hall International Visiting Fellowship, University of Cambridge; and the Zimmerman

Fund for Scientific Innovation Awards in Brain Science, part of

Brown’s Carney Institute for Brain Science.