History of anti-vax racism goes back to earliest vaccines

Paula Larsson, University of Oxford

|

| Anti-vaxxers protest outside Governor Andrew Cuomo’s official residence in Albany, New York in June 2020. (Shutterstock) |

There has been a recent increase in anti-vaccination conspiracy theories, misinformation campaigns and protests in various countries.

And while many accuse anti-vaxxers of a selfish disdain for the health and safety of others, there is a underlying aspect of these movements that needs to be more widely recognized.

Vaccine resistance movements have always been led by white, middle-class voices and promoted by structures of racial inequality.

Racist language to discredit vaccination

The intrinsic racism of anti-vaccination movements began with their historical origin in the 19th century.

Inoculation originally referred to the older form of vaccination, where pus was taken from the pustule of someone with a mild form of smallpox and purposely scratched into the arm of a healthy person. This would ideally convey a mild form of the disease and thereby protect the recipient from more deadly forms.

This type of inoculation had its foundation in a number of non-western cultures before it was incorporated into western medical practice. Indeed, inoculation was practiced in China for centuries before it made its way to Europe, as well as in the Middle East and North Africa.

Its use in North America was initiated by the knowledge of an enslaved man, Onesimus, who famously taught the procedure to puritan minister Cotton Mather during a smallpox outbreak in the early 18th century.

These non-western origins fueled some anti-vaccination criticisms during the 19th century. Opponents to the practice declared it a “filthy, useless and dangerous rite” akin to using the “charms and incantations of an African savage.”

By the turn of the 20th century, racialized language began to appear in anti-vaccination dialogues which, on the surface, had little to do with race. These racial slurs served the purposes of anti-vaccinationists who sought to discredit the practice.

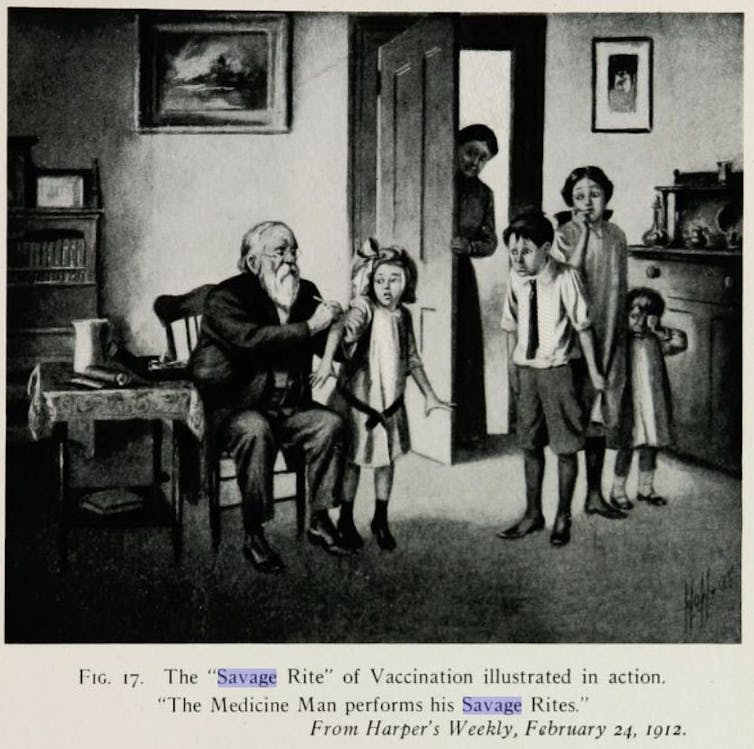

One of the most potent examples of this was in 1920, when vocal anti-vaccination writer Charles Higgins published a book against vaccination. Throughout this work he consistently referred to vaccination as a “savage rite” performed by “the Medicine Man” on helpless innocent children.

|

| An illustration from Charles Higgins book ‘Horrors of Vaccination Exposed and Illustrated’ (Internet Archive) |

Medical freedom, white freedom

The racialized language utilized by these early anti-vaxxers was all the more potent when weaponized by white leaders of anti-vaccination leagues (or organizations).

Between 1860 and 1920, numerous anti-vaxx leagues were founded in Britain, the United States and Canada.

One of their main arguments was that compulsory enforcement was a “tyrannical interference with the rightful liberties of the people,” an accusation often levelled at health officials attempting to increase vaccine uptake in the general public.

These people used their social standing to loudly condemn perceived limitations of their rights, while blindly ignoring the systemic absence of the same freedoms for racialized and low-income communities.

In North America, the freedom to choose vaccination was already defined by racial identity in many places. Throughout this period, Indigenous children in Canada were forced to attend residential schools, where vaccination was either implemented or ignored at the will of federal or school officials, with little regard for parental or individual choice.

On the West Coast, civic public health officials actively enforced compulsory vaccination on Asian communities based on racial profiling during disease outbreaks. In 1900, city health officials in San Francisco issued mandatory plague vaccination orders for all Chinese individuals after a few cases of plague were found in the city.

American writer Harriet A. Washington has vividly demonstrated how Black communities were frequently enrolled in medical research trials for testing new medical treatments and vaccines, often without their knowledge or consent.

Yet the medical oppression of non-white communities was ignored by anti-vaccination leaders, who instead used their platforms to retain the medical freedoms of dominant white communities.

|

| Two men read notices pasted to a wall in downtown Chinatown, San Francisco, 1896-1906. (Library of Congress) |

In present times, the leaders of anti-vaccination movements are still predominantly white, with many receiving millions in revenue from their activities.

More concerning is that they have begun to deliberately target racialized communities with anti-vaccine disinformation and propaganda. Recognizing the societal factors that have eroded trust in medical institutions, anti-vaxxers are attempting to direct this distrust to benefit their own cause.

Through their actions, anti-vaxxers deliberately seek to increase the risk of infection in already vulnerable populations. We saw this in 2017 after an outbreak of measles in Minnesota among the Somali-American community in Minneapolis.

Anti-vaxxers staged two public meetings in the community, encouraging parents to avoid vaccination and pushed the false claim that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine is linked to rising rates of autism. The result was a drastic reduction in MMR vaccination uptake between 2004 and 2014 — dropping from 92 per cent to 42 per cent — and one of the largest measles outbreaks in the state in three decades.

Deliberate targeting has been amplified even further this year in the attempt to discredit COVID-19 vaccines. The prominent anti-vaccine organization Children’s Health Defense recently released a film aimed at fuelling distrust in vaccination among Black Americans.

Anti-vaccination leaders have also begun to co-opt narratives of persecution and suffering for their own purposes. Last month, a Washington state official wore a yellow Star of David to protest vaccine mandates, while prominent anti-vaccine voice, Naomi Wolf, was scheduled to headline a fundraiser for “liberation” from vaccine mandates on Juneteenth.

|

| A large group of people gather in Union Square, New York City at a ‘Freedom Rally’ to protest vaccines and masks in March 2021. (Shutterstock) |

It’s not the white, middle- and upper-class anti-vaccination leaders who suffer most from a diminished herd immunity and increased prevalence of vaccine-preventable illnesses.

Such individuals are generally protected by the same social and racial privileges that have historically enabled them to continuously gain a large following.

In the end, the individuals who bear the brunt of an increased burden of disease are those from historically vulnerable communities whose concerns continue to be co-opted and overshadowed by anti-vaccination activists.![]()

Paula Larsson, Doctoral Student, Centre for the History of Science, Medicine, and Technology, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.