In South County, several shoreline fire districts bring in hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes and other revenue annually but spend much of it on expenses more in line with a private beach club, not a fire department. That has drawn the ire of beachgoers who are being blocked from the shore.

By Alex

Nunes, The Public's Radio · Reprinted with the permission of The Public's Radio

[EDITOR'S

NOTE: Read previous stories on shoreline fire districts and view

interactive graphics at this link.]

As

a pair of tennis players rallied back and forth, Will Collette stood nearby in

disbelief.

They

were playing earlier this summer on a court owned by the Quonochontaug Central

Beach Fire District in Charlestown, R.I., part of the district’s 28-acre

recreational facility, also home to a basketball court and softball field.

The

compound isn’t the only place for property owners to have fun in Quonochontaug

Central Beach. The fire district has no fire department, but it does have a

second tennis property nearby and about 2.5 acres of beachfront land for

swimming and sunbathing.

“It

is mind-boggling,” said Collette, a Charlestown resident. “I tell people about

this and they go, ‘What? They’re a fire district? How does that happen?’”

Fire

districts in Rhode Island like Quonochontaug Central Beach were originally

created as a way to provide fire protection to outlying areas. Today, there are

about 40 of them statewide. They levy taxes on property owners and provide

public services. They are governed by leaders elected by the small group of

district property owners but can make decisions independent of city and town

governments. And some critics say a small group of coastal fire districts has

twisted “public services” to spend money on perks for property owners, while

sometimes not even having their own fire departments at all.

The

Public’s Radio investigated seven fire districts that each own coastal property

in South County — Weekapaug, Watch Hill, Misquamicut, Shelter Harbor, Shady

Harbor, Quonochontaug Central Beach, and Bonnet Shores — and found that none of

them spent more than 38% of their expenses on firefighting services in their

last reported fiscal year, either through spending on their own fire

departments or by contracting with other districts. Bonnet Shores Fire District

actually spent no money on fire service at all, because its residents are

covered by the town of Narragansett.

Some of the fire districts provide garbage collection and some of them clear the roads of snow in winter. But the fire districts also spend significant portions of their budgets on cleaning up beaches, security guards that keep their beaches private, lifeguards and boat docks. Contrast that with the Dunn’s Corners Fire District in Westerly, which doesn’t own shoreline property but covers other districts that do. It spent more during the 2020 fiscal year on fire services than it raised in taxes.

The

Quonochontaug Central Beach Fire District does provide services like water

service and garbage pickup. But public records show it also spent 10% of its

nearly $350,000 in total expenses on beaches, dunes, docks, police and

security, tennis and what it calls “civic improvements.”

“It's

a beach club. It's a country club. It's a neighborhood association,” said

Collette, who co-writes a blog called Progressive Charlestown. “I have total

respect for people who will put their lives on the line and go rush into

fires...It's an insult to them for this group to call itself a fire district

and not do that.”

Watch Hill Fire District rakes in rental income

Spending

reports the fire districts file with the state auditor and obtained by The

Public’s Radio reveal the extent to which the state has allowed the

quasi-municipal entities to operate differently than other special fire

districts. Take the Watch Hill Fire District in Westerly, for example. It is

run almost like a business — so well diversified that if it were a true

for-profit corporation, it might attract the attention of investors.

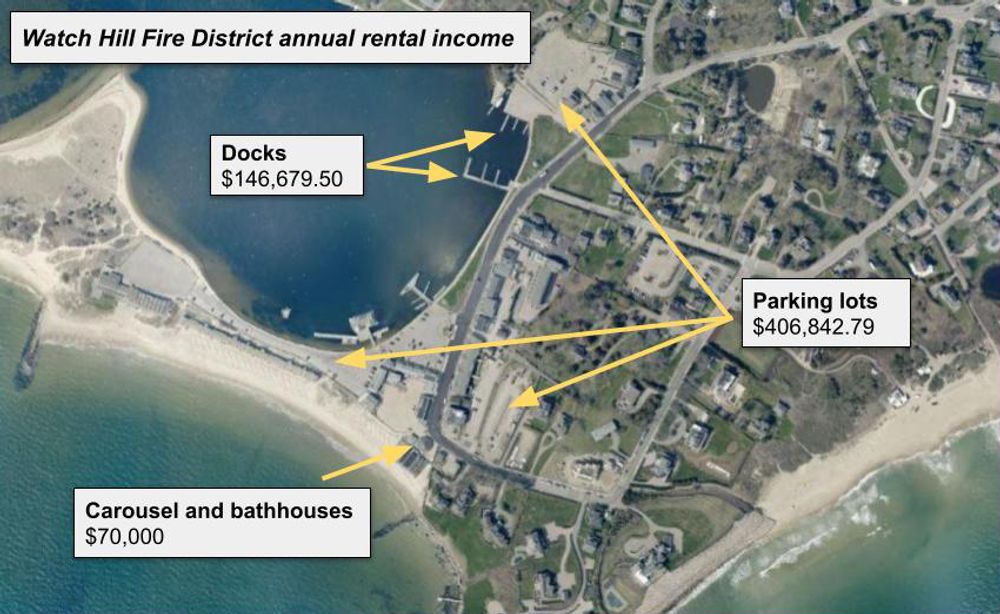

The

district brings in revenue from boat dock rentals, bathhouse rentals, multiple

parking lots, and an antique carousel. In total, the Watch Hill Fire District

pulled in annual rental income that surpassed $620,000 in the 2020 fiscal year,

including a parking lot the district leases to the Watch Hill Yacht Club for

more than $40,000. That is in addition to the $747,000 the district collected

in tax revenue from property owners. It also sold a property to the yacht club

for $2 million in 2018.

|

| A map shows the annual rental income brought in by the Watch Hill Fire District. ALEX NUNES/THE PUBLIC'S RADIO |

The district may have lots of cash, but the state also agreed to give it a $250,000 state grant last year, in part to prevent flooding in the lot used by the yacht club. The district asked for the public money to improve public access to nearby Napatree Point, but a constant lack of available parking in Watch Hill in the summer often keeps people from accessing the area anyway. The fire district charges the public $40 or $50 for a parking space depending on the day, but fire district property owners park for free.

Unlike many of the other coastal fire districts, Watch Hill does have its own fire department. Fire-related costs make up about a third of total expenses, according to documents it files with the state, totaling about $480,000 in the 2020 fiscal year. The district also spent more than $460,000 on what it calls its “Park Commission,” to maintain its beach, bathhouses and docks; hire parking lot employees; and provide a salary for a superintendent.

Property owners with low property taxes

|

| Charlestown resident Will Collette poses for a photo at the Shady Harbor Fire District boat launch in Charlestown. ALEX NUNES/THE PUBLIC'S RADIO |

The

Shady Harbor Fire District owns more than 19 acres of land, including a

quarter-acre boat launch on the shores of Quonochontaug Pond, but pays no

property taxes to Charlestown. The state legislature baked a tax exemption into

the district’s charter in the 1960s.

Will

Collette said that means he and other Charlestown residents are underwriting

the good times being had by property owners in Shady Harbor.

“The

fact that this piece of property, which could very well be worth about a

million bucks being where it's situated and taxed accordingly, pays no taxes

means that everybody else who does pay taxes on a fair assessment of their

property covers what they don’t,” Collette said.

The

Bonnet Shores Fire District also pays no taxes to the town of Narragansett

because state lawmakers let the district hold its properties in a tax-exempt

land trust.

On

its website, the land trust encourages fire district property owners to

consider donating their own land for similar benefits, telling them they can

“avoid future taxes, fees, and other liabilities!”

Elsewhere,

other fire districts pay low taxes because their land is zoned “open space and

recreation.”

In

one case in Westerly, the Weekapaug Fire District’s 8.82-acre Fenway Beach is

assessed at about $350,000, but across the Weekapaug Breachway, 2.66 acres

owned by the private Seaside Beach Club is valued at more than $4.5 million.

The fire district spends about $3,900 on annual property taxes for Fenway

Beach; Seaside Beach Club pays more than $60,000 on its land and buildings.

|

| A map shows the difference in property assessments and tax payments for the Weekapaug Fire District's Fenway Beach and the private Seaside Beach Club. ALEX NUNES/THE PUBLIC'S RADIO |

Using tax money to prevent public access

Most

troubling to many residents in coastal communities is the fact that fire

districts use their own tax funding to block the public from accessing the

shoreline, which is undoubtedly public land.

A

third of the Weekapaug Fire District’s $590,000 in expenses went to beaches and

public safety. The district uses some of that money on security guards to keep

the public away.

The Weekapaug Fire District also retained a local attorney at $350 per hour specifically to help it fight beachgoers who want to increase public access in the area. Earlier this summer, the attorney, Thomas J. Ligouri, Jr., filed a 152-page submission with the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council, arguing that the district can keep a contested right of way blocked off from the public.

The

actions by the fire district don’t sit well with people like former Westerly

Town Council member Jean Gagnier, who used his time on the council to fight for

increased public access to the shore.

“It doesn't seem fair to me,” he said. “Might be legal. A lot of these things are legal. But then the fairness and the justice perspective — they come up a little different on that score.”

‘We’re not really a fire district’

Carol

O’Donnell, chair of the Bonnet Shores Fire District Council, said criticism of

her fire district is based on the public’s misunderstanding. If people want to

get some proper perspective, she said, then they need to stop thinking of her

fire district as a “fire” district.

“We're

not really a fire district,” she said. “Just the name of it’s a fire district.

We're more of a glorified homeowners association. I'm thinking of it as a community

with all of our owners and taxpayers that are here. We're more like an

association.”

But

thanks to their state charters, fire districts like Bonnet Shores are public

entities with considerable powers. They can issue bonds, sell a resident’s home

if they don’t pay their taxes, enact ordinances, and impose fines. The state

has even given districts the authority to imprison people.

O’Donnell

pointed out that Bonnet Shores does provide services like lifeguards for its

private beaches, garbage and recycling pickup, access to a community center,

and a playground for kids.

“We have more or less our little group, if you will, of a fire district, which is like a homeowners [association] that takes care of things that the town doesn't, because this community chooses to do that,” O’Donnell said.

|

| A sign at the entrance of the Bonnet Shores Fire District in Narragansett. ALEX NUNES/THE PUBLIC'S RADIO |

John

Marion, executive director of the good government group Common Cause Rhode

Island, says he is concerned about the power these fire districts exert.

When

Marion hears about their beach club perks and how little the districts actually

spend fighting fires, he sees red flags, and he questions the state’s role in

enabling all of this.

“Populations,

or subsets of the population, have really just sort of used these fire

districts as a vessel to serve their narrow private interests,” Marion said.

“The people of Rhode Island should be skeptical that our state government is

sort of giving its blessing to these entities that really aren't serving the

purpose for which they were originally created.”

Although

local residents and fire districts have been at odds through the years, there

hasn’t been much interest from state and town officials in addressing these

concerns. A special commission on shoreline access was recently formed by the

Rhode Island House, but its chairperson says fire districts won’t be a focus.

Alex

Nunes can be reached at anunes@thepublicsradio.org