The mystery bureaucrats managing your prescription drugs

By Linda L Ujifusa, Esq & J Mark Ryan, MD FACP in UpRiseRI

SHORT ATTENTION SPAN ALERT:

This is a long article. It needs to be. If you can only handle Tweet-length pieces, you should move along now. However, if you live in Rhode Island and take prescription medicines through any insurance plan, including Medicare D, this article discusses issues that directly affect you and also offers suggestions for actions you should take. - Will Collette

SUMMARY:

About

40% of Americans struggle to afford their regular prescription medicines – with

1/3 saying they have skipped filling a prescription one or more times, because

of the cost. COVID-19 has exacerbated the problem by causing job and

health insurance loss and delaying routine care.

Rhode

Island policymakers know skyrocketing prescription drug prices must be better

controlled.

Unfortunately,

they have ignored a key cost driver: Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs).

PBMs

such as CVS Caremark, Express Scripts and OptumRx “manage” prescription drug

benefits on behalf of insurers and siphon off enormous revenues in the complex

non-transparent system that gets drugs from manufacturers to patients.

Other

states are doing a much better job monitoring and controlling PBMs and have

saved consumers and tax payers hundreds of millions of dollars.

Rhode

Island should follow their lead.

To

urge RI policymakers to take action, please sign this petition.

A

fully footnoted version of this article is available to download here.

What

are PBMs?

In

between most patients and healthcare providers are middlemen health insurers

(“payers”) who take money from patients, pay some to healthcare providers, and

keep some for themselves. These multiple payers cause the United States to

spend about twice per capita what other industrialized nations with “single

payer” spend and they get better universal healthcare.

In the middle of payers, patients and pharmacies, there are Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs).

PBMs:

Middlemen for middlemen

PBMs

are for-profit companies that “manage” prescription drug benefits for more than

266 million Americans on behalf of payers, including private

insurers, Medicare Part D drug plans, government employee plans,

large employers, and Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs).

PBMs

help payers:

- create a list of covered drugs for plans (“a formulary”);

- manage drug utilization by enrollees (e.g., by setting co-pays, prior authorization policies, etc.);

- reimburse pharmacies for providing the enrollee drugs.

This

article will focus on:

- Who are Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

- How PBMs Harm Consumers and Taxpayers

- PBM Oversight in Other States

- Potential Roadblocks to RI Reforms

- How RI Can Rein in PBMs

WHO

ARE PHARMACY BENEFIT MANAGERS (PBMS)

PBMs

began in the 1970s as small independent middlemen between insurers and

pharmacies, taking a set fee for processing claims.

Today,

three PBMs control 80% of the market and are part of large vertically

integrated conglomerates that include health insurance companies and pharmacies (including

“specialty

pharmacies”)

- CVSCaremark – 32% market share – parent company: CVS (Aetna)

- Express Scripts – 24% market share – parent company: Cigna

- OptumRx – 21% market share – parent company: UnitedHealth

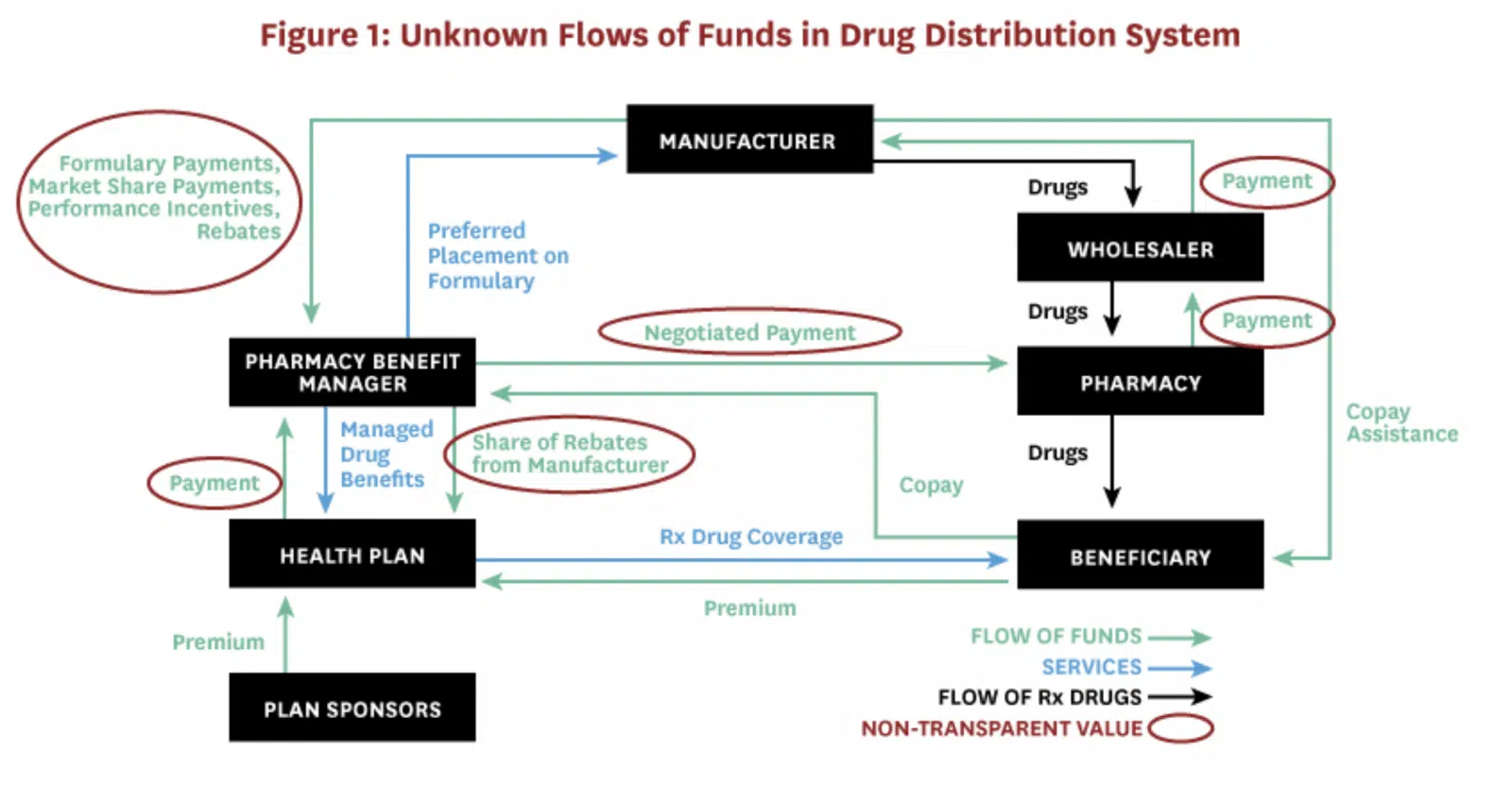

PBMs are also part of a complex non-transparent distribution system that gets drugs from manufacturers to beneficiaries (see Figure 1).

Source: https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/state-drug-pricing-transparency-laws-numerous-efforts-most-fall-short/, adapted from, Sood, N., et al., “Flow of Money Through the Pharmaceutical Distribution System,” USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy white paper.

In

this system, businesses can keep payments and discounts between themselves

confidential, but analyses show that pharmaceutical manufacturers make the most

profits for developing and manufacturing prescription drugs AND:

Revenues

of top PBM conglomerates exceed those of top pharmaceutical manufacturers.

PBM

conglomerates rank 4th (CVS), 5th (UnitedHealth

Group) and 13th (Cigna) on the Fortune 500 list ranking largest

corporations by revenue.

PBMs

drive revenues for their parent companies:

- “CVS Health’s Pharmacy Services (PBM) segment will make 46% of $324 Billion in 2021 revenues for the company and remains key to its revenue growth.”

- In 2019, Cigna’s total revenues more than doubled ($14.3 billion to $38.2 billion) and its Express Scripts Holding Co. unit was the “driving force” behind the $22 billion surge.

- UnitedHealth’s Optum subsidiaries collected more profit in the fourth quarter of 2019 ($3 billion) than United Healthcare insurance ($2.1 billion)

HOW

PBMs HARM CONSUMERS AND TAXPAYERS

1.

PBMs get legal kickbacks (“rebates”) from drug manufacturers for putting

certain drugs on formularies

When

PBMs create a list of covered drugs, they negotiate with drug manufacturers for

legal kickbacks (“rebates”) in exchange for giving certain drugs preferred

placement on formularies (e.g., Tier 1 with no co-pay, etc.).

Kickbacks

are generally illegal under federal law, but PBMs are given a “safe harbor” and

a federal rule making PBM rebates illegal has been delayed.

PBMs

have a conflict of interest developing formularies because they get

more money for shareholders by choosing an expensive drug with a higher rebate

than by choosing the most effective or affordable drug for consumers.

Although

PBMs pass rebates to insurers (who may be their parent companies) and claim

this will result in lower premiums and co-pays, analyses show there is no such

trickle down to consumers.

In

fact, drug manufacturers cover PBM rebates by raising their

list prices for drugs and consumers pay a higher co-pay

because they pay a % of the higher list prices.

At

$143 billion in 2019, it is estimated that rebates added nearly 30 cents per

dollar to the price consumers pay for prescriptions.

2.

PBMs overcharge payers (including state Medicaid) and underpay pharmacies

because they can keep the difference (“spread”) between what they are paid and

how much they reimburse pharmacies

Multiple

states have found PBMs problems related to their keeping the “spread.” An

Ohio audit, for example, found that in one year, “CVS Caremark and

UnitedHealth’s OptumRx PBMs reaped more than $223 million—and made an 8.8%

profit—by overcharging Medicaid managed care plans, underpaying pharmacies,

and pocketing the difference.”

Ohio

found the spread came to $5.70 per prescription across all brand-name and

generic drugs and that Ohio could have gotten the same services for $1.90 per

prescription or less by switching to a fee-based model – where pharmacies are

reimbursed their acquisition cost plus a set administrative fee.

Ohio

ordered managed-care plans in the state to terminate PBM spread pricing

contracts for 2019.

3.

PBMs “claw back” and keep excess consumer co-pays

Consumers

are often unaware they could have paid less if they had NOT used their

insurance (for example, when a co-pay is $10, but the drug price without

insurance is $7).

Although

consumers should be allowed to recover such overpayments, PBMs are the ones who

“claw back” overpayments – and keep them.

A study by

researchers at the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for

Health Policy & Economics found that because of PBM claw backs, customers

overpaid for their prescriptions 23 percent of the time.

4. PBMs

profit from a federal program (“Section 340B”) meant to help low income

patients

In

1992, Congress enacted Section 340B of the Public Health Service Act mandating

that pharmaceutical manufacturers provide outpatient drugs at significant

discounts to certain “covered entities.” 340B’s original purpose was to

allow a handful of safety-net hospitals that cared for the poor to obtain drugs

at substantially reduced prices.

Changing

federal laws caused the number of entities eligible for 340B discounts to

explode so that today, there are now about 5,000 covered entities and 20,000

affiliated sites, as well as, “30,000 pharmacy locations—half of the entire

United States pharmacy industry – now act[ing] as contract pharmacies for the

hospitals and other healthcare providers that participate in the 340B

program.” 340B discounted drugs make up “more than 8% of the total United

States. drug market and about 16% of the total rebates and discounts that

manufacturers provide.”

This

large, complex and relatively unknown program is detailed here,

but PBM problems generally involve their engaging in “discriminatory reimbursement,”

e.g., offering 340B entities lower reimbursement rates than those offered to

non-340B entities.

Currently,

the federal 340B statute allows PBMs to make significant revenues and not pass

money to those Section 340B intended to help.

5. PBM

conglomerates own retail, mail order and specialty pharmacies and can work

against consumer interests by:

- Setting low reimbursements for their competitors – a cause of local independent pharmacies disappearing.

- Pharmacy Steering – PBMs “steer” customers to pharmacies, including mail order and specialty pharmacies, with whom they are affiliated, e.g., by requiring a higher copay if the patient obtains the drug from a non-affiliated pharmacy.

- Pharmacist gag orders – despite a federal law and a new 2021 Rhode Island law that prohibits PBMs from preventing pharmacists from discussing cheaper options, the consumer still has to ask and may not be told all options.

6.

PBMs can hide profits

Reasons

for the lack of transparency noted in Figure 1 include:

- PBMs keeping their negotiated discounts and rebates confidential – even from a recent federal Senate committee investigating insulin prices.

- PBMs disguising profits, e.g., as “rebate management fees” and “savings.”

- PBMs controlling their own audits, e.g., by having the right to veto auditors, determine frequency of audits, require auditors to sign “Confidentiality Agreements,” etc.

7.

PBM “Utilization Management” can harm patients

PBMs

claim to implement “utilization management” strategies on behalf of payers to

benefit payers AND consumers. These strategies can include:

- “Prior authorization,” which requires patients to get third-party approval prior to getting the medicine prescribed by their healthcare provider.

- “Step therapy,” also known as “fail-first,” “sequencing,” and “tiering,” which requires patients to start with lower-priced medications before being approved for originally prescribed medications.

- “Non-medical drug switching” which forces patients off their current therapies for no reason other than to save money. “Tactics include increasing out-of-pocket costs, moving treatments to higher cost tiers, or terminating coverage of a particular drug.

Unfortunately,

such utilization management can also harm consumers by making providers spend

excessive time on administrative tasks, delaying and discouraging patient care,

and adversely affecting clinical outcomes.

PBM

Oversight in Other States

Rhode

Island has some PBM-related laws and regulations, but other states are more

aggressively investigating and reining in PBMs to better protect consumers and

tax payers.

A

recent Supreme Court case, Rutledge v.

PCMA, supports states taking more actions to regulate PBMs.

Some

actions other states are taking include:

1. Imposing

transparency reporting requirements

27

states with private insurance companies (Managed Care Organizations –

MCOs) managing their Medicaid programs reported they will have transparency

reporting requirements in place in FY 2020. For example:

Texas passed

a 2019 law requiring PBMs to report information to the state and discovered,

“Since 2016, through a complex rebate and price concession process, the PBM

industry in Texas pocketed more than $350 million in revenue, while passing a

mere $16 million in savings to enrollees.”

2.

Investigating PBMs

Several

states have investigated or are currently investigating PBMs.

Florida:

State audit found “prescription markups” by PBMs cost Florida’s Medicaid system

$113.3 million in 2020 ($89.6 million in “spread costs”).

Kentucky: Attorney

General investigating PBMs for overcharging the state and discriminating

against independent pharmacies after state discovers PBMs kept $123.5 million

in spread annually.

Massachusetts:

Investigation found prices charged by PBMs for generic drugs were often

“markedly higher” than the actual cost of the drug in both Mass Medicaid

Managed Care and Commercial Plans, “contributing to higher health care

spending” (e.g., up to 111% more for certain drugs than in fee-for-service

state-managed Medicaid program).

Mississippi:

Auditor General is investigating PBMs suspected of overcharging state Medicaid

and the Mississippi State and School Employees’ Life and Health Insurance Plan,

which covers nearly 200,000 state employees, retirees and their families after

audit found PBMs were paid more than $1.1 billion; sometimes as much as $25

million a month.

Pennsylvania:

Auditor General found between 2013 and 2017, the amount that taxpayers paid to

PBMs for Medicaid enrollees more than doubled from $1.41 billion to $2.86

billion and is urging greater transparency and more state control.

3. Carving

out PBMs from managing Medicaid pharmacy benefits

Four

states reported in 2019 that they generally “carve out” pharmacy benefits from

their Medicaid managed care programs (Missouri, West Virginia, Tennessee

and Wisconsin) and other states were considering doing so.

West

Virginia “carved out” PBMs, including Express Scripts and CVS, from its

Medicaid managed-care program and began running the program as a

fee-for-service program – eliminating spreads and reducing administrative fees.

It expected to save $30 million a year—about 4 percent of the state Medicaid

drug spending. In fact, WV Medicaid saved $54.4 million in its first year and

$122 million that used to go to out-of-state PBMs instead went to West Virginia

pharmacies in the form of fixed dispensing fees.

Ohio

contracted with a single PBM for Medicaid after undertaking the

state audit described

above and the State Auditor concluding, “It is now overwhelmingly apparent that

PBMs are operating the biggest shell game in modern history, and we are all

paying for it.

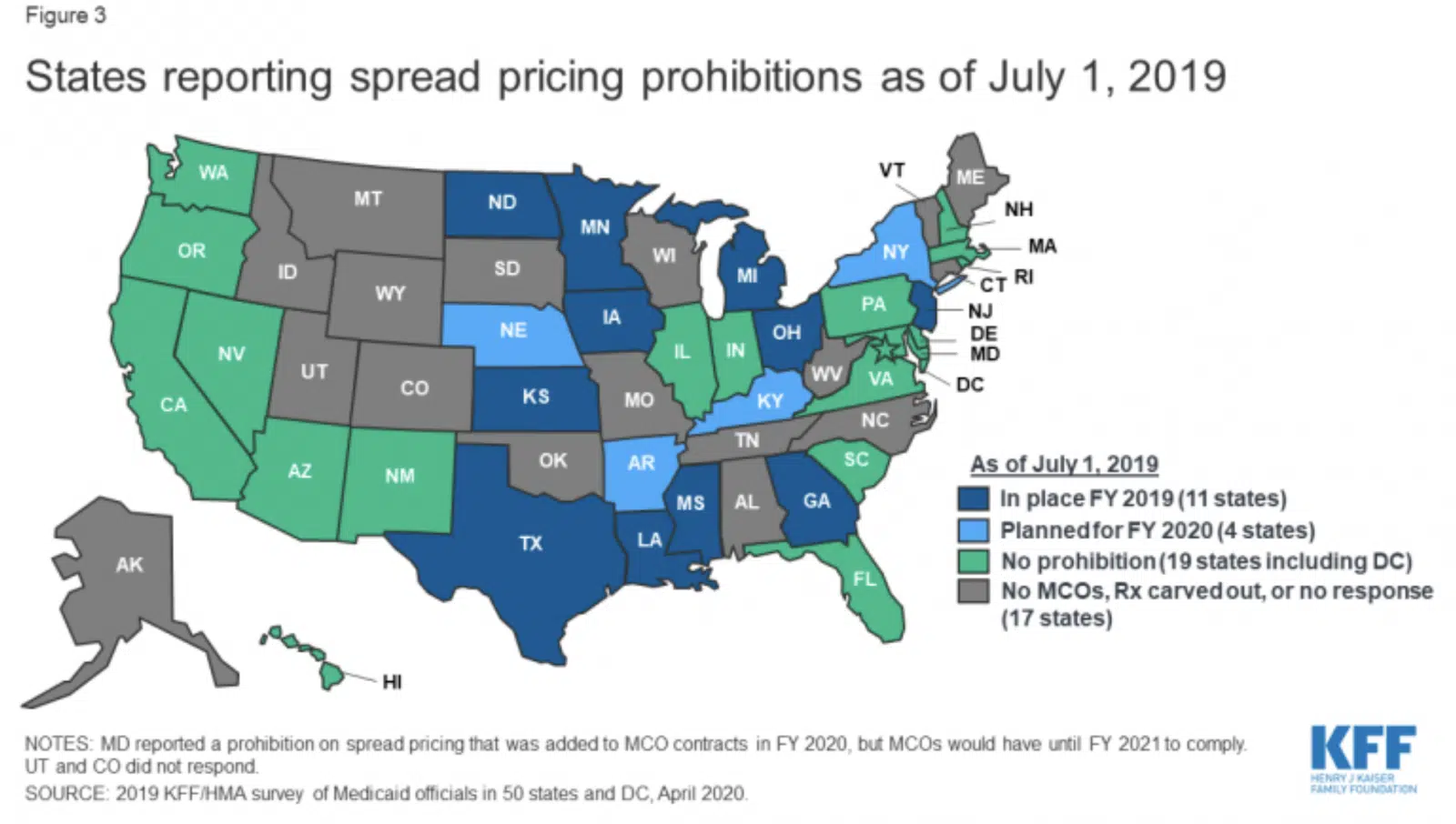

4.

Prohibiting spread pricing

About

17 states reported a spread pricing prohibition would take effect by January

2021 (Figure 3).

Arkansas: Passed

a law, upheld by the Supreme Court, that required all PBMs to reimburse

pharmacies at a price equal to or higher than what the pharmacy paid to buy the

drug from a wholesaler.

Maryland: Banned

spread pricing after a state Medicaid report found PBMs pocketed “spread” of

$72 million annually.

Ohio: Ended

spread pricing contracts with PBMs and switched to a pass-through model

following a state audit that found PBM profit accounted for 31.4% ($208.4

million) of the $662.7 million paid by Ohio Medicaid MCOs for generic drugs

5.

Restricting PBM rebates

Ohio:

rebates and discounts must be passed back to the state.

Maine:

required PBMs to pass rebates and other “compensation” to consumers or insurers

(who must in turn apply the funds to “offset the premium for covered persons”).

West

Virginia: now handles pharmacy benefits for both state workers and Medicaid

recipients through the West Virginia State University of Pharmacy, saving $38

million in its first year.

About

17 states: have enacted stronger laws requiring PBMs to disclose rebate information.

6. Prohibiting

“claw backs”

About

38 states have prohibited PBM “claw backs.

7.

Prohibiting pharmacy discrimination

Georgia,

Louisiana, Minnesota and Utah have passed legislation banning the practice

of “pharmacy steering.”

Kentucky created

an act that requires PBMs to provide greater transparency and “fair and

reasonable” reimbursements.

8.

Restricting Section 340B reimbursements

About

11 states: have passed legislation to prohibit PBMs from reimbursing 340B

covered entities less than other entities who get their standard reimbursement

rate.

9.

Limiting “Utilization Management”

Prior

Authorization – 12 states (including RI) have legislation protecting drug

classes or categories from using Prior Authorization in some or all

circumstances, and most (excluding RI) also apply such statutory limits to

Medicaid MCOS.

Step

Therapy – 11 states have passed and many more are

considering legislation to limit Step Therapy, e.g., Arkansas became

the first state to pass a comprehensive step-therapy ban.

Non-Medical

Drug Switching – Several states have prohibited or introduced bills

limiting non-medical switching.

Potential

Roadblocks to RI Reforms

1.

CVS-Aetna-Caremark

CVS

Caremark is a large Rhode Island-based corporation whose single biggest source

of revenue is its PBM business.

Although

the full extent of corporate influence is difficult to discern, it can be

significant, and:

CVS

pays lobbyists large sums (e.g., Pharmacy Care Management Association -PCMA,

$3,962,000 in 2020) to advocate in RI against PBM reforms.

CVS

contributes to RI elected leaders who have not voted to investigate nor control

middlemen payers and PBMs as healthcare cost drivers.

CVS

has threatened to cut RI jobs to influence proposed legislation.

Since

2010, CVS has secured over $240 million in Rhode Island tax breaks despite

apparently cutting its RI workforce from about 12,000 to 3,000 (including

getting over $20 million in FY2016 and cutting 247 jobs without notice to

the state) and despite taxpayers paying for at least 300 RI CVS employees on

Medicaid.

2.

The Rhode Island Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS)

RI

EOHHS has advocated for RI Medicaid to be “managed” by private insurance

companies – despite lack of evidence that privatizing Medicaid serves consumers

and taxpayers better than the fee-for-service state-run Medicaid program

previously in place.

Today,

about 90% of RI Medicaid is run by managed care organizations (MCOs): (Neighborhood

Health Plan of Rhode Island, Tufts Health Plan and United

Healthcare Community Plan) who are paid approximately

$1.7 billion annually (about 40%

state/60% federal funds) – even though the RI Auditor General,

since 2009, has flagged inadequate state MCO oversight.

RI

MCO contracts, scheduled to expire in April 2022, are missing PBM oversight and

restrictions, e.g., they:

- do not have reporting requirements to identify the amount of PBM spread.

- do not make statutory limitations on prior authorizations also apply to Medicaid managed care PBMs.

3.

RI Office of Health Insurance Commissioner

Rhode

Island is the only state in the country to have a separate “Office of Health Insurance Commissioner”

(OHIC) whose #1 listed purpose is to “guard the solvency of health

insurers.” See RIGL §

42-14.5-2.

Although

OHIC may also seek to protect consumers, it appears to prioritize health

insurer economic interests, e.g., raising health insurance premiums during the

COVID-19 pandemic.

OHIC

recognizes prescription drug costs are major healthcare cost drivers, however,

its analyses fail to consider what role insurers and PBMs play in skyrocketing

healthcare cost.

4.

RI Health Care Costs Trends Project

The

latest major research effort to study Rhode Island healthcare costs is

the RI Health

Care Cost Trends Project (“Cost Trends Project”), a

“private-public partnership” funded by a $550,000 grant from the Peterson Center on Healthcare (PCH),

founded by Pete Peterson,

a “power from Wall Street to Washington,” who championed the theory that

“entitlement programs” like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, would wreck

the US economy. PCH-sponsored analyses do not analyze whether middlemen

insurers and PBMs could be cost drivers.

The

Cost Trends Project’s goals are to “identify cost and utilization drivers,

develop an annual health care cost growth target, and inform system performance

improvements.”

After

spending its initial $550,000 grant, the Cost Trends Project has produced analyses

that ignore how insurers and PBMs affect health care costs and could not

establish an accurate “annual health care cost growth target.”

A

majority of the Cost Trends Project’s steering committee and staff:

- have ties to insurance company or PBM middlemen as current or former high level employees or

- are employed by organizations that rely heavily on insurer/PBM funding; or

- have a history of producing healthcare cost analyses that fail to analyze middlemen and focus on reining in providers, despite evidence that such policies are ineffective.

What

RI Should Do

Rhode

Island legislative and executive branch officials should follow the lead of

other states more aggressively reining in PBMs, including:

- Require PBMs to disclose information that results in effective ongoing state oversight and control of PBMs.

- Pursue appropriate civil and criminal investigations and actions.

- Carve out PBMs from Medicaid Managed Care Organization (MCO) contracts set to renew in April 2022.

- Restrict Insurer/PBM middlemen unjustified revenues, such as those arising from spread pricing, “claw backs,” “pharmacy steering,” discriminatory reimbursements, manufacturer rebates, and Section 340B transactions.

- Restrict harmful Insurer/PBM utilization management practices, such as, Prior Authorization, Step Therapy and Non-medical Drug Switching.

- Establish an unbiased research group to analyze ALL potential healthcare cost drivers, including private middlemen insurers and PBMs.

WHAT

YOU CAN DO

Sign this

petition to ask state legislators, OHIC and EOHHS to reform

oversight and control over RI PBMs.

Linda L Ujifusa, Esq., Chair, RI Healthcare Access & Affordability Partnership, www.rihealthcare.org, 401-655-1446

J. Mark Ryan, MD, FACP, Chair, Physicians for a National Health Program – RI Chapter