Canine Parasite Has Evolved Resistance to All Treatments

By UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA

|

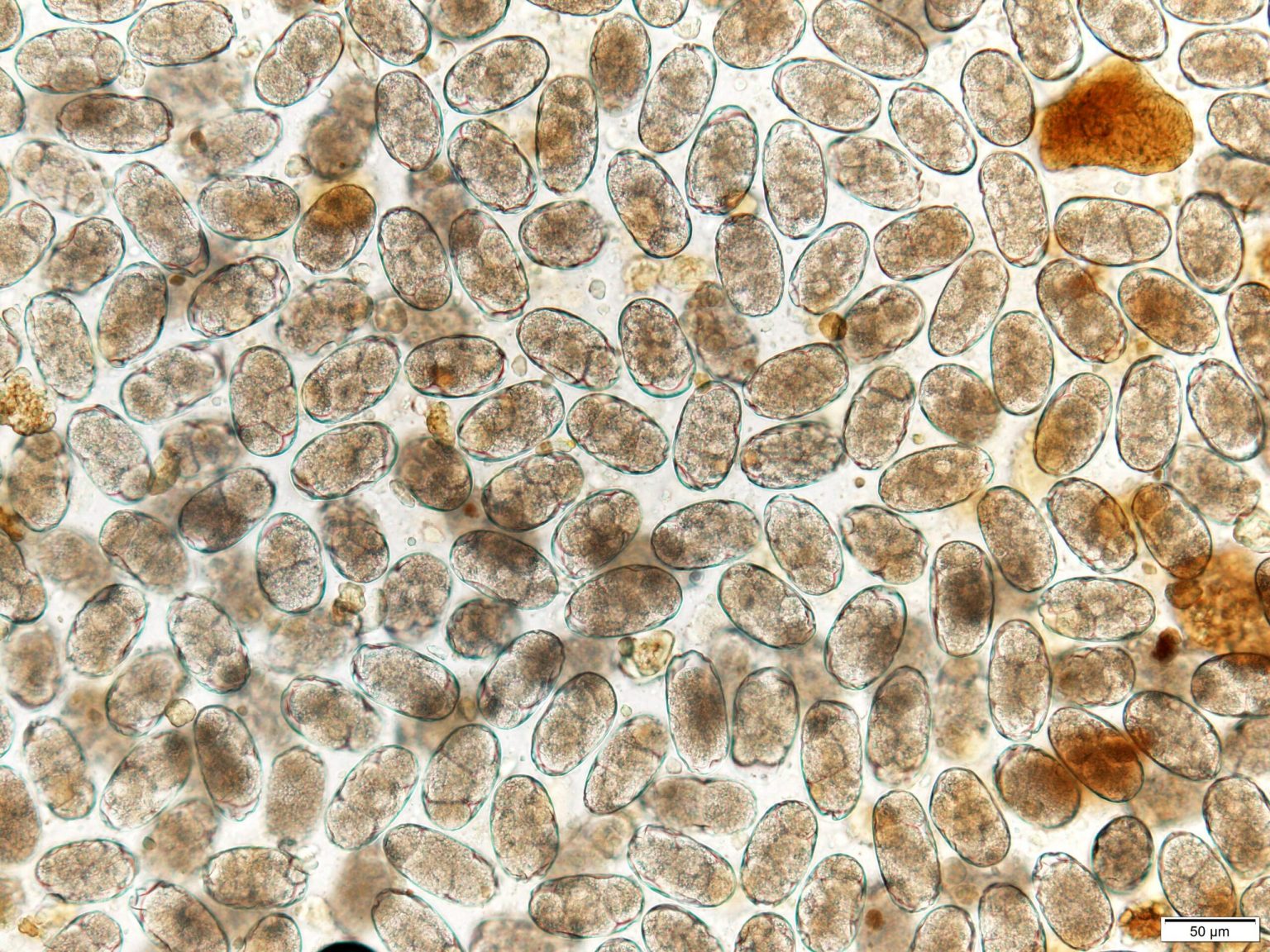

| Hookworm eggs are seen under a microscope. Credit: University of Georgia |

Hookworms have evolved to evade all FDA approved medications veterinarians use to kill them.

Hookworms are one of the most common parasites plaguing the

companion animal world.

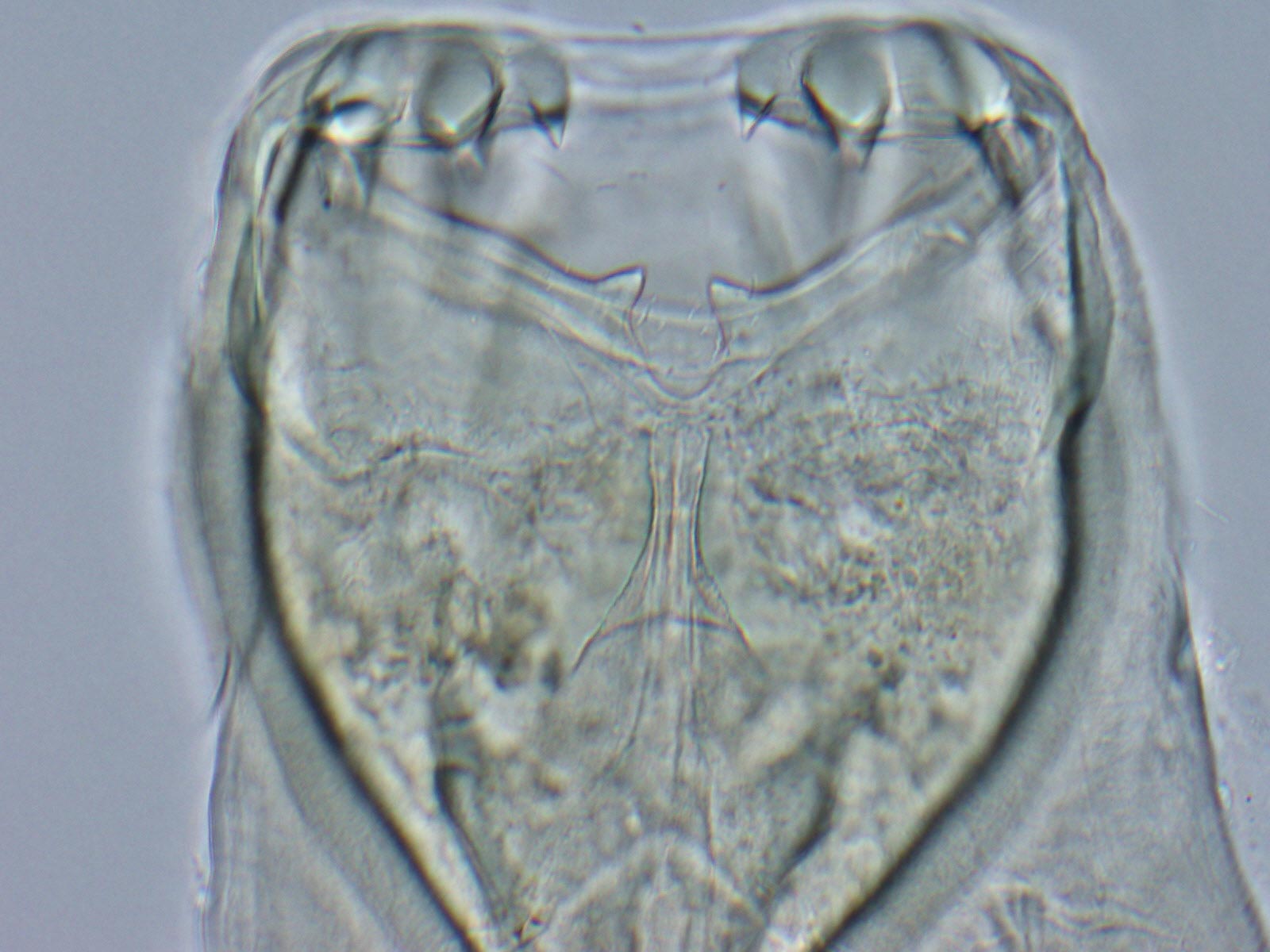

They use their hooklike mouths to latch onto an animal’s

intestines, where they feast on tissue fluids and blood. Infected animals can

experience dramatic weight loss, bloody stool, anemia and lethargy, among other

issues.

Now they’ve become multiple-drug resistant, according to new

research from the University of Georgia.

Right now, U.S. veterinarians rely on three types of drugs to kill the hookworms, but the parasites appear to becoming resistant to all of them. Researchers from the UGA College of Veterinary Medicine first reported this concerning development in 2019, and new research, published recently in the International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance, provides deeper insight into where the problem started and how bad it’s since become.

For the present study, the researchers focused on current and former racing greyhounds. Dog racetracks are particularly conducive to spreading the parasite due to the sandy ground of the facilities, an ideal breeding ground for hookworms. Because of the conditions, all the dogs are dewormed about every three to four weeks.

After analyzing fecal samples from greyhound adoption kennels,

three veterinary practices that work with adoption groups and an active racing

kennel, the researchers found the parasites were highly prevalent in the breed.

Four out of every five greyhounds tested came up positive for hookworms. And

the ones that tested negative are probably also infected, said Ray Kaplan, the

study’s corresponding author and a former professor of veterinary parasitology

at UGA.

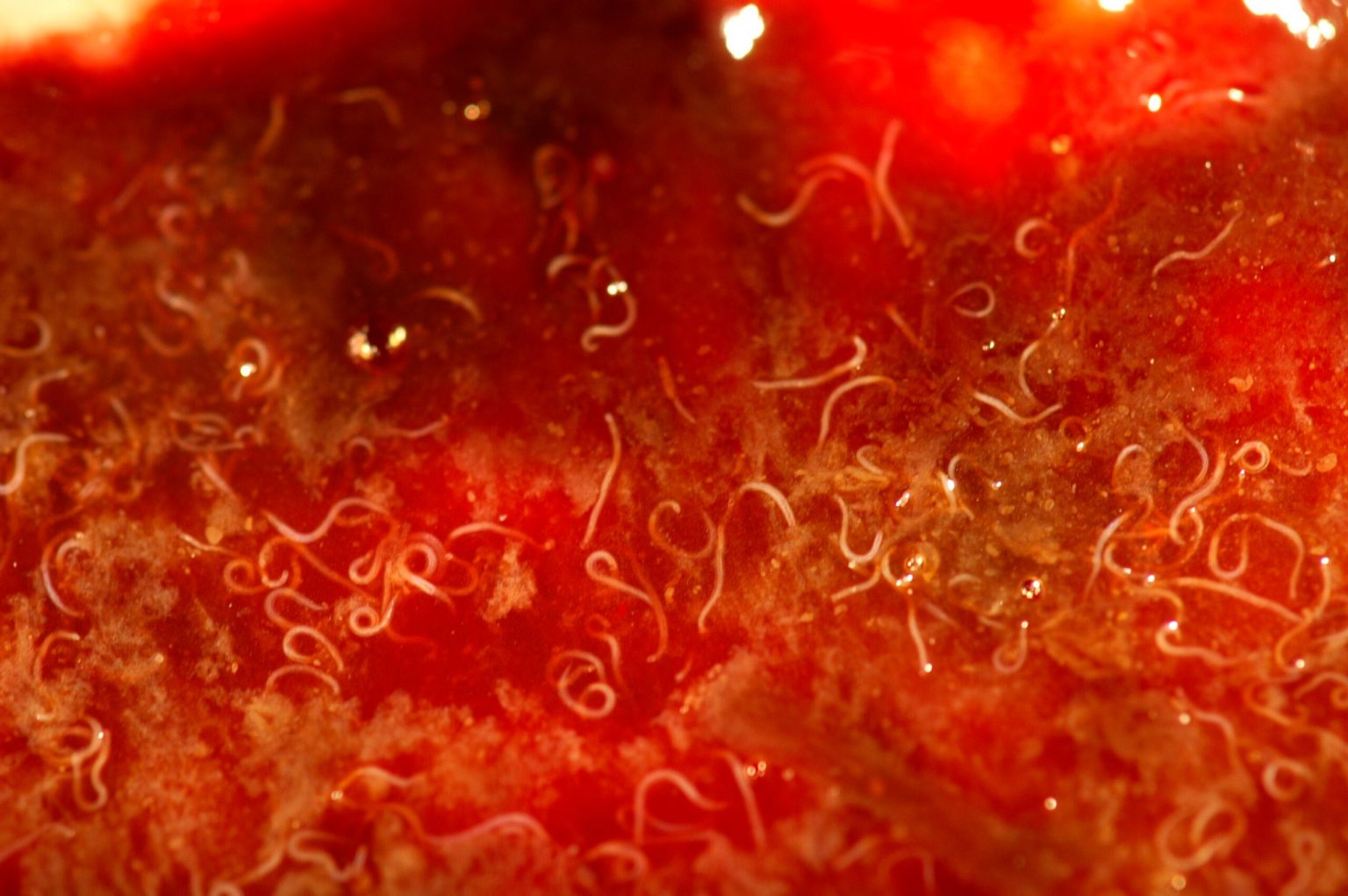

Hookworms are visible within the intestine of a deceased puppy.

Credit: University of Georgia

Hookworms can sometimes “hide” in tissues, where they won’t reproduce and shed eggs until the infection worsens and leaks into the dog’s intestines.

But perhaps more alarming, the team saw that the dogs still had

high levels of infection with hookworms even after they were treated for them.

The study marks the first demonstration of widespread

multiple-drug resistance in a dog parasite reported in the world.

Parasite

mutations

In situations where there are a lot of dogs infected with a lot of

parasites, such as on racing dog breeding farms and kennels, there are many

more opportunities for parasites to develop rare mutations allowing them to

survive the dewormer treatments. If dewormers are applied frequently, the newly

emerging resistant worms will survive and pass on the mutation that helped them

sneak past the drug to their offspring.

With repeated treatments over time, most of the drug-susceptible

worms at the farm or kennel will be killed, and the resistant worms will then

predominate.

Compounding the problem, veterinarians don’t typically test

animals after treatment to ensure the worms are gone, so the drug-resistant

worms go unnoticed until the dog has a heavy infection and starts showing signs

of hookworm disease.

“Personally, I would not take my dog to a dog park. If your dog picks up these resistant hookworms, it’s not as easy as just treating them with medication anymore.”

— Ray Kaplan, professor of veterinary parasitology

The researchers found that almost all the fecal samples tested

positive for the mutation that enables hookworms to survive treatment with

benzimidazoles, a broad-spectrum class of dewormers used in both animals and

humans. Although a molecular test does not yet exist to test for the resistance

to the other two types of drugs, other types of testing by the team showed that

the hookworms were resistant to those drugs as well.

“There’s a very committed greyhound adoption industry because they

are lovely dogs,” said Kaplan. “I used to own one. But as those dogs are

adopted, the drug-resistant hookworms are going to show up in other pet dogs.”

Hookworms get their name from their hook-shaped mouths shown

here under a microscope. Credit: University of Georgia

One possible breeding ground for a potential drug-resistant hookworm outbreak is also the place many dog owners use to exercise their animals: dog parks.

“Personally, I would not take my dog to a dog park,” Kaplan said.

“If your dog picks up these resistant hookworms, it’s not as easy as just

treating them with medication anymore. Until new types of drugs are available,

taking your dog to a dog park has to be considered a risky activity.”

The

consequences

Dogs don’t have to ingest the worms to become infected. Hookworm

larvae live in the soil and can also burrow through the dog’s skin and paws.

And female dogs can pass the parasite on to their puppies through their milk.

If that’s not scary enough, dog hookworms can also infect humans.

The infection doesn’t manifest in the same way in people, but

after the worms penetrate the skin, they cause a red, very itchy rash as they

travel under the skin. As the number of drug-resistant worms grows, they’ll

also pose a risk to humans.

Previously, doctors would treat patients with an ointment that

contains a dewormer along with a corticosteroid. “Unfortunately, that’s not

going to work against these drug-resistant hookworms,” Kaplan said.

But hope isn’t entirely lost.

Kaplan and Pablo Jimenez Castro, lead author of the study and a

recent doctoral graduate from Kaplan’s lab, found in another recent study that

these multiple-drug resistant dog hookworms do appear to be susceptible to

emodepside, a dewormer currently only approved for use in cats in the U.S. But

use of this cat drug on dogs should only be performed by a veterinarian, as it

requires veterinary expertise and supervision.

Based in part on Castro’s work, the American Association of

Veterinary Parasitologists recently formed a national task force to address the

issue of drug resistance in canine hookworms.

Reference: “Multiple drug resistance in hookworms infecting

greyhound dogs in the USA” by Pablo D. Jimenez Castro, Abhinaya Venkatesan, Elizabeth Redman, Rebecca Chen, Abigail Malatesta, Hannah

Huff, Daniel A. Zuluaga Salazar, Russell Avramenko, John S. Gilleard and Ray

M.Kaplan, 2 September 2021, International Journal for

Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2021.08.005

Co-authors on this study include Abigail Malatesta, a veterinary

student from Tuskegee University, Hannah Huff, currently a veterinary student

at the University of Georgia, and researchers from the University of Calgary in

Canada.