Justifying slavery, dismissing new historical insights, disparaging protest are not what we expect from the state's historian laureate

By Phil Eil in Uprise RI

Last October, I wrote a piece for Uprise about Rhode Island “historian laureate” Patrick Conley, and what makes his continued grip on this state-sanctioned title so strange.

In the piece, I pointed out that, while Conley does have solid academic credentials, he’s also got a lot of other baggage.

He worked closely

for disgraced Providence mayor Buddy Cianci. He once spearheaded a failed

“personal quest” to develop Providence’s industrial waterfront into “$300

million mixed-use development.”

He holds, or once held, the distinctions – which he touts on his own website –

of “Providence’s largest, private landowner (in terms of number of parcels

owned)” and “holder of more Rhode Island real estate titles (via tax sale

purchases) than any person in Rhode Island history.”

I also wrote about his history of arguments that seem

out-of-sync not just with Rhode Island’s progressive electorate, but our

current cultural moment of reckoning with the past. To pick just one example:

as protests against police brutality roiled the nation following the death of

George Floyd, Conley wrote about

“The current irrational and hyperbolic political discourse – both right and

left, but especially left.”

And, in addition, I wrote about the troubling circumstances of

Conley’s re-appointment to this position in early 2020. Unlike the first

go-round, there had been no public call for applications this time. The

transaction took place unannounced and behind the scenes, with only a small,

after-the-fact acknowledgement to Public’s Radio reporter

Ian Donnis.

Unfortunately, the things that irked me about Conley last year

have not only persisted – I daresay they’ve gotten worse, and with higher

stakes. Conley remains our “laureate,” and he continues to disseminate his

stale, embarrassing, poorly-argued opinions in our state’s newspapers – always

accompanied by a reminder of his honorary title that conveys the idea he’s

speaking for all Rhode Islanders.

In December he wrote a piece for

the Providence Journal attempting to refute accusations of

racism while also, bafflingly, telling Black folks why they shouldn’t celebrate

Juneteenth on its widely-accepted date.

In August, he penned a letter to The

Independent that was ostensibly about an overlooked Rhode

Island-raised Olympic athlete, but which quickly veered off-subject to a

defense of the Founding Fathers’ slaveholding.

“Some presentistic accounts of American History condemn

Washington, Jefferson, and Madison for slaveholding, while ignoring the fact

that in their time slavery was global and an accepted practice by humans,

whether in America, Africa, or Asia,” he wrote. “These Founders were born and

raised in the slave-ridden culture of Virginia from which they could not

escape.”

Then, this weekend, the Journal ran an op-ed in

which Conley defended Christopher Columbus’s record of slaveholding with that

same rationale: “Such a brutal fate dealt to humans in 1500 shocks us in 2021,

but enslavement of an enemy was common practice at that time in Europe, Asia,

Africa, and among most Native American tribes.”

Defending the slaveholding of prominent historical figures is

apparently a crusade for Conley.

Now, I’m not interested in using this space, and your precious time, to rebut Conley’s points. That would be too easy and obvious. (Although it’s worth pointing out that one of the key points on which he bases his latest flimsy argument – that the Caribs were cannibals, and, thus somehow more deserving of the fate that befell them – has been thoroughly debunked.) Nor am I interested in re-treading too much of the terrain I covered last time.

But I am compelled to revisit the subject of Conley. Because

while I find his views reprehensible, and the means by which he retained this

honorary position disturbing, I am, in a way, grateful he remains so publicly

visible.

Indeed, I’ve come to believe that the fact that we are stuck

with Conley contains lessons that speak louder than any historical wisdom that

he has consciously tried to impart.

It’s worth emphasizing, at the top, that the Pat Conley story

isn’t just about Conley. It’s about the fact that, seemingly whenever he has an

idea, no matter how half-baked or poorly argued, he has a place for it in our

state’s paper of record, The Providence Journal.

At a moment when, according to a recent Columbia

Journalism Review report,

“racial and ethnic minorities comprise almost 40 percent of the US population,

yet they make up less than 17 percent of newsroom staff at print and online

publications, and only 13 percent of newspaper leadership,” Conley represents

the ongoing imbalance of who gets heard in our most widely-read print outlets.

As a longtime reader of, and reporter on,

the Providence Journal, I’m quite confident that if the Journal did

the kind of bold

soul-searching recently undertaken at the New Yorker into

racial inequality in its ranks, it would yield similar, if not even more

troubling results. And each time they publish Conley, they remind us of their

inability to, or apathy about, correcting this lack of diversity on their

opinion pages.

And Conley’s power isn’t just in his access to our most famous

newspaper. Since I wrote about him last fall, the picture of his reappointment

has come into slightly clearer focus. Documents that

I obtained, via an open-records request, show that in a letter to the Secretary

of State following his in-person meeting in February 2020, Conley referred to

his “anticipated re-appointment as Historian Laureate” as if it were a fait

accompli.

Elsewhere in the letter, he noted – quite oddly for a historian

– “My influence with the legislature is not as great as it once was, but it is

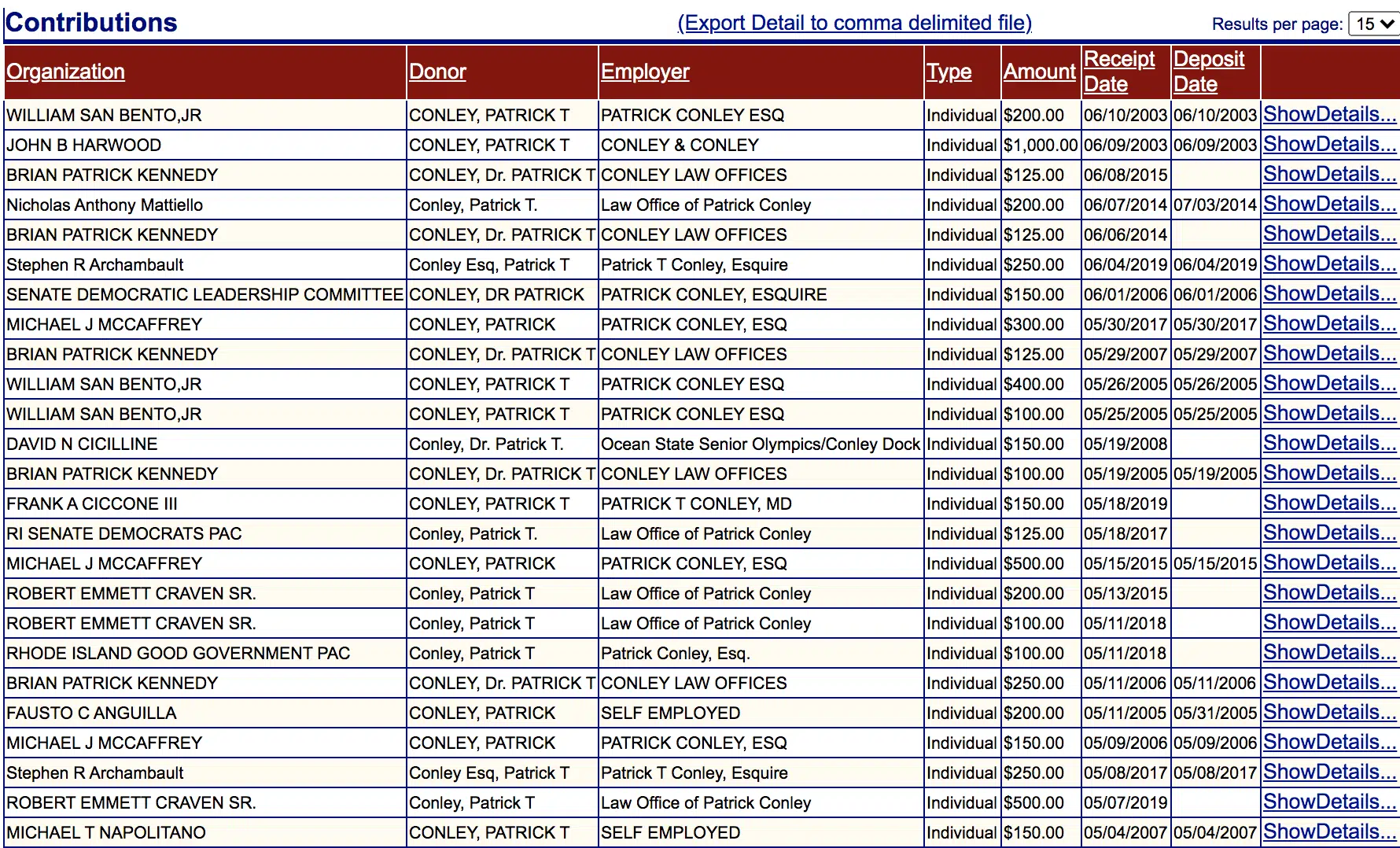

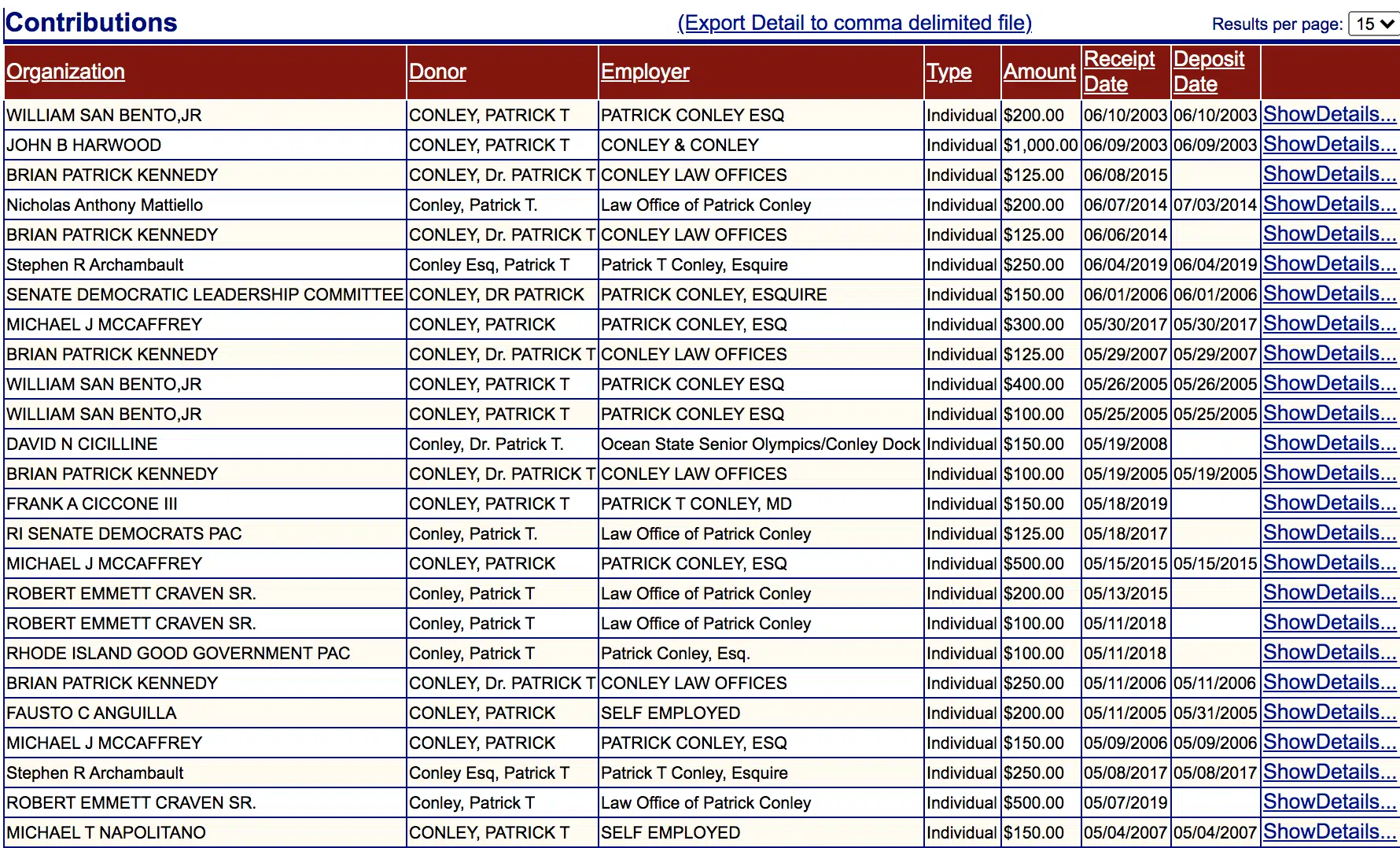

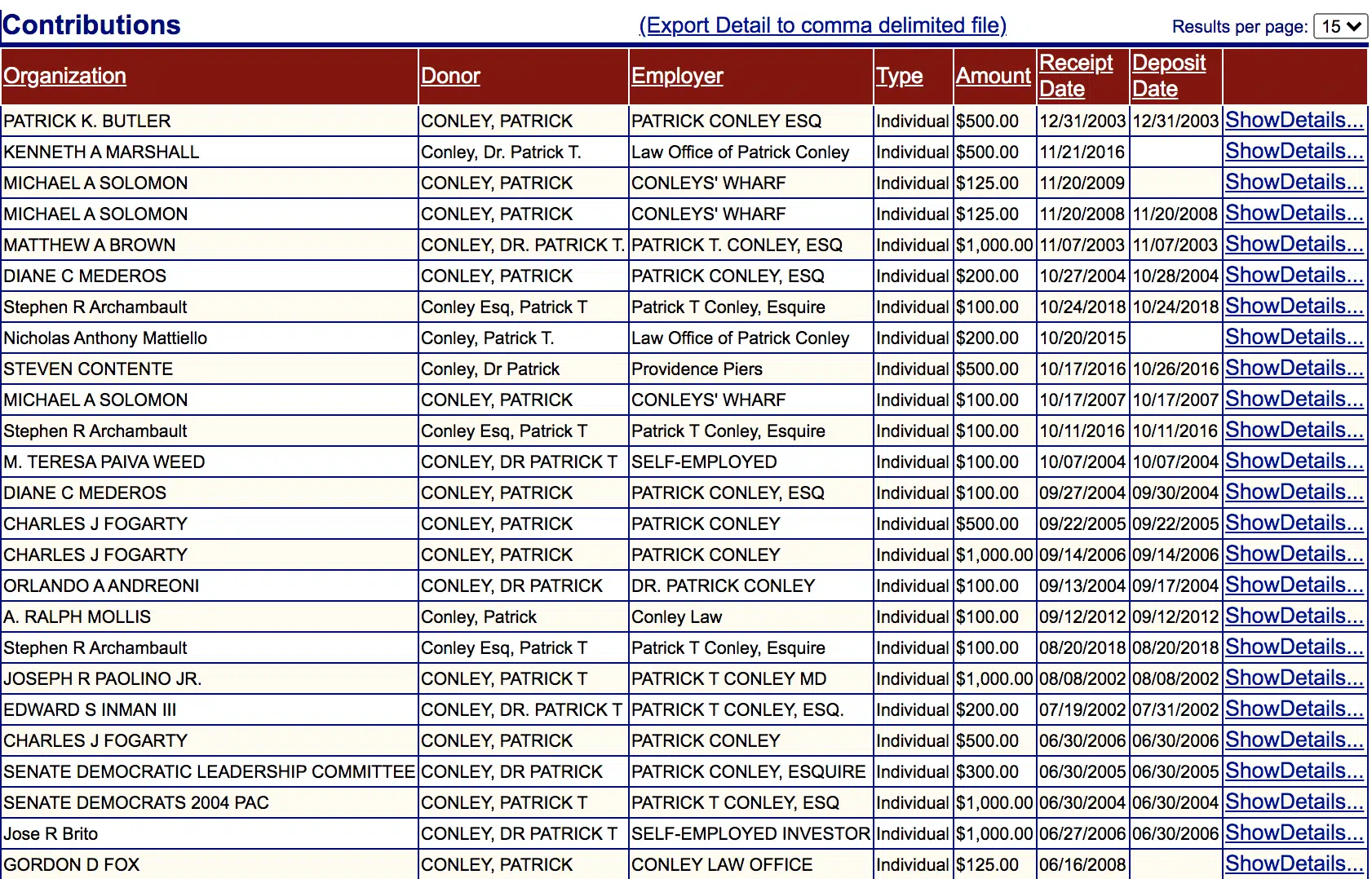

still substantial.” Meanwhile, a quick check of the state campaign

finance-track portal shows that

Conley has given more than $30,000 in political contributions in Rhode Island

since the early 2000s. How many of our citizens have the time, access, and

resources, to pull off a similar maneuver?

Partial list of Conley's political donations. The remainder appear at the end of this article. Screen shot from the RI Board of Elections database.

Gorbea, the Secretary of State who OK’d the reappointment, is

now a candidate for

governor. And Gonzalo Cuervo, Gorbea’s former chief of staff who the

APRA-released emails show played a role in brokering a meeting with Conley and

his boss, has declared his candidacy for

mayor of Providence.

Before either candidate proceeds much further in their bids for

two of the state’s highest offices, we deserve an explanation of how this

reappointment happened, and the extent of their involvement.

Conley is symbolic in other ways as well. At a time when the

majority of Congresspeople

are millionaires, and when our Senate is the oldest in

history, he reflects the ways in which our representatives –

be they elected or honorary – are demographically dissimilar from their

constituencies.

At age 83, Conley represents a cohort that is just shy of 18 percent of the population,

and his wealth surely makes him close to, if not a member of, the proverbial

“one percent.” And we know, based on his outspoken opposition to removing

“Plantations” from the state name and the results of the

ballot question on that issue, that he was a member of that minority

position.

He represents, in other words, an exceedingly narrow portion of

Rhode Island’s populace, yet we see his arguments in print time and again.

This, of course, doesn’t mean he shouldn’t ever be published. It just means we

deserve a “laureate” with a little more humility about the limitations of his

personal views and experiences.

And this brings me to the thing about Conley that I find most

bothersome.

You would think that any conscientious “laureate” would

acknowledge the pliability of history, the power dynamics involved in how it is

written, the limitations of his own (white, wealthy, male, politically

connected) perspective, and invite a robust discussion.

But Conley seems utterly uninterested in, or incapable of,

interrogating the ways that his privileges might influence his view of events.

His interest, as illustrated in op-ed after op-ed, seems to lie in stamping out

any attempt, however modest, at historical re-examination.

He will not budge in his views of Columbus or the Founding

Fathers, and he doesn’t believe that we should either. His style does not

invite further debate; he wants to snuff it out. He has written that

“Presentism is History’s cardinal sin” as if this is the only sin a historian

can commit.

At a moment the city of Providence is engaged in a “Truth-Telling,

Reconciliation and Municipal Reparations Process”; when the state’s

lone law school is mandating a

course on race and the law; when the University of Rhode Island

releases a surprisingly strongly-worded

message commemorating Indigenous People’s Day, Conley remains

resolute. He is not rising to meet the moment; he is trying to yell loud enough

to drown it out.

One can expect that, when history is written about our current

our post-George Floyd, post-#MeToo era, it might be dubbed “The Great

Re-Examination.” But this is also a time of backlash.

Fox News, that unrelenting firehose of white grievance, remains

the nation’s most watched

network. State legislatures are passing laws that make it harder

to talk about race

in the classroom and protest

injustice in the streets. Countless politicians and pundits

are building careers out of anti-”woke” posturing and demagoguery. Conley is

our local poster boy for these trends.

A few years ago, I wrote an article about

the influential, yet deeply racist, Rhode Island-born “cosmic horror” author

H.P. Lovecraft. And one of the most memorable quotes came from the legendary

English comics author Alan Moore, who framed Lovecraft’s importance in terms of

the cultural shifts that took place during his lifetime, included advances in

women’s suffrage, leaps in understanding of outer space, the Russian

revolution, new highly visible LGBT communities in American cities, and the

largest wave of migrants and refugees the U.S. had ever seen.

“In this light it is possible to perceive Howard Lovecraft as an

almost unbearably sensitive barometer of American dread,” Moore wrote. “Far

from outlandish eccentricities, the fears that generate Lovecraft’s stories and

opinions were precisely those of the white, middle-class, heterosexual,

Protestant-descended males who were most threatened by the shifting power

relationships and values of the modern world.”

Reading Conley requires less interpretative effort. He writes

nonfiction, not fiction, and there are no aliens or tentacled monsters to

decode. His views are not buried in the subtext; they’re right there on the

surface of the letters and op-eds that he routinely fires off to Rhode Island

newspapers.

But, in Conley, I believe we have a similar barometer of white

male anxiety for our own era. And here lies his value, however ugly and

unintentional.

Conley may not be particularly useful for performing the actual

duties of our historian laureate. His arguments are lazy. His myriad

privileges, conflicts of interest, and decades of political maneuvering go

unmentioned and unexplored.

He seems incurious about developments in his discipline. But as

a rich, old, reactionary white guy with an outsized platform and an influential

position that he maintained through an undemocratic process, he reflects many

of the current political winds in the United States. His grip on this honorary

position, and his frequent cringe worthy op-eds, are an uncomfortable reminder

of how power functions in this country.

Patrick Conley is a terrible historian laureate. But he’s an

excellent reminder of how much work remains to make our little state as just,

compassionate, egalitarian, and genuinely democratic as it deserves to be.