Scientists discover new science in the gut and, potentially, new leads on how to treat irritable bowel syndrome and other disorders

Michigan State University

Researchers

at Michigan State University have made a surprising discovery about the human

gut's enteric nervous system that itself is filled with surprising facts. For

starters, there's the fact that this "second brain" exists at all.

"Most

people don't even know that they have this in their guts," said Brian

Gulbransen, an MSU Foundation Professor in the College of Natural Science's

Department of Physiology.

Beyond

that, the enteric nervous system is remarkably independent: Intestines could

carry out many of their regular duties even if they somehow became disconnected

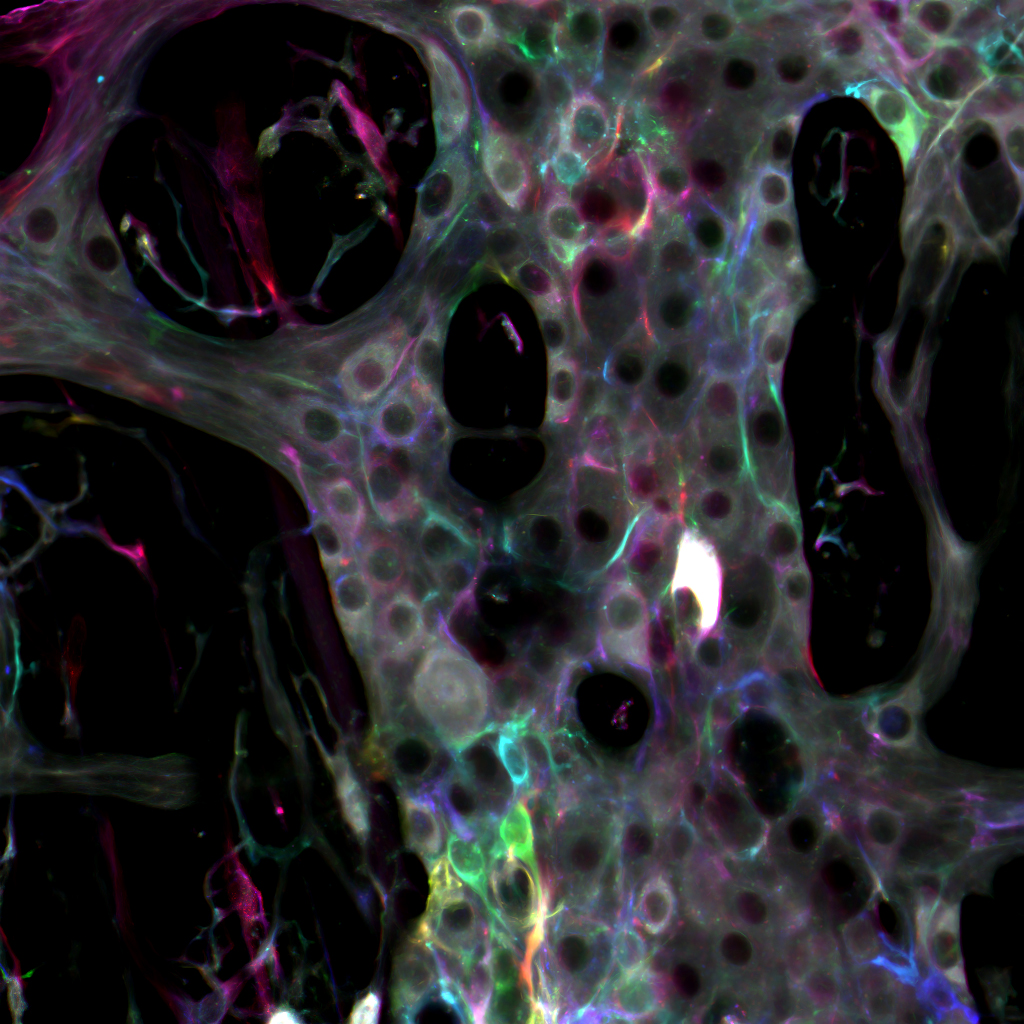

from the central nervous system. And the number of specialized nervous system

cells, namely neurons and glia, that live in a person's gut is roughly

equivalent to the number found in a cat's brain.

"It's

like this second brain in our gut," Gulbransen said. "It's an

extensive network of neurons and glia that line our intestines."

Neurons are the more familiar cell type, famously conducting the nervous system's electrical signals. Glia, on the other hand, are not electrically active, which has made it more challenging for researchers to decipher what these cells do. One of the leading theories was that glial cells provide passive support for neurons.

Gulbransen

and his team have now shown that glial cells play a much more active role in

the enteric nervous system. In research published online on Oct. 1 in the Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences, the Spartans revealed that glia act in

a very precise way to influence the signals carried by neuronal circuits. This

discovery could help pave the way for new treatments for intestinal illness

that affects as much as 15% of the U.S. population.

"Thinking

of this second brain as a computer, the glia are the chips working in the

periphery," Gulbransen said. "They're an active part of the signaling

network, but not like neurons. The glia are modulating or modifying the

signal."

In

computing language, the glia would be the logic gates. Or, for a more musical

metaphor, the glia aren't carrying the notes played on an electric guitar,

they're the pedals and amplifiers modulating the tone and volume of those

notes.

Regardless

of the analogy, the glia are more integral to making sure things are running

smoothly -- or sounding good -- than scientists previously understood. This

work creates a more complete, albeit more complicated picture of how the

enteric nervous system works. This also creates new opportunities to

potentially treat gut disorders.

"This

is a ways down the line, but now we can start to ask if there's a way to target

a specific type or set of glia and change their function in some way,"

Gulbransen said. "Drug companies are already interested in this."

Earlier

this year, Gulbransen's team found that glia could open up new ways to help

treat irritable bowel syndrome, a painful condition that currently has no cure

and affects 10% to 15% of Americans. Glia could also be involved in several

other health conditions, including gut motility disorders, such as

constipation, and a rare disorder known as chronic intestinal

pseudo-obstruction.

"Right

now, there's no known cause. People develop what looks like an obstruction in

the gut, only there's no physical obstruction," Gulbransen said.

"There's just a section of their gut that stops working.

Although

he stressed that science isn't at the point to deliver treatments for these

problems, it is better equipped to probe and understand them more fully. And

Gulbransen believes that MSU is going to be a central figure in developing that

understanding.

"MSU

has one of the best gut research groups in the world. We have this huge,

diverse group of people working on all the major areas of gut science" he

said. "It's a real strength of ours."