Here’s why the ocean is pouring in more often

|

| People walked down a flooded sidewalk in Annapolis, Maryland, on Oct. 29, 2021. AP Photo/Susan Walsh |

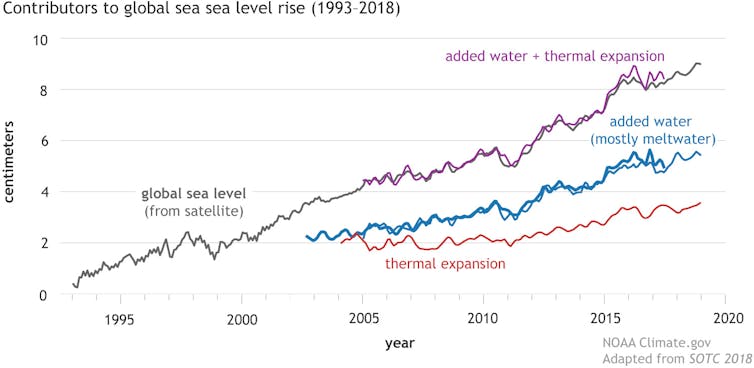

Since 1880, average global sea levels have risen by more than 8 inches (23 centimeters), and the rate has been accelerating with climate change.

Depending on how well countries reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in the coming years, scientists estimate that global sea levels could rise by an additional 2 feet by the end of this century.

The higher seas means when storms and high tides arrive, they add to an already higher water level. In some areas – including Charleston, South Carolina, where a storm and high tide on Nov. 5, 2021, sent water levels about 8 feet above normal – sinking land is making the impact even worse.

I’m a geoscientist who studies sea level rise and the effects of climate change. Here’s a quick explanation of two main ways climate change is affecting oceans levels and their threat to the world’s coasts.

Ocean thermal expansion

Climate change, fueled by fossil fuel use and other human activities, is causing average global surface temperatures to rise. This is leading the ocean to absorb more heat than it did before the industrial era began. That, in turn, is causing ocean thermal expansion.

Thermal expansion simply means that as the ocean heats up, sea water molecules move slightly farther apart. The farther apart the molecules are, the more space they take up.

That expansion leads to the ocean rising higher onto land.

During the past several decades, about 40% of global sea level rise was due to the effect of thermal expansion. The ocean, which covers just over two-thirds of the Earth’s surface, has been absorbing and storing more than 90% of the excess heat added to the climate system due to greenhouse gas emissions.

Melting land ice

The other major factor in rising sea levels is that the increase in average global temperatures is melting land ice – glaciers and polar ice sheets – at a faster rate than natural systems can replace it.

When land ice melts, that meltwater eventually flows into the ocean, adding new quantities of water to the ocean and increasing the total ocean mass.

During the past several decades, about 50% of global sea level rise was induced by land ice melt.

Currently, the polar ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica hold enough frozen waters that if they melted completely, it would raise the global sea level by up to 200 feet, or 60-70 meters – about the height of the Statue of Liberty.

Climate change is melting sea ice as well. However, because this ice already floats at the ocean’s surface and displaces a certain amount of liquid water below, this melting does not contribute to sea level rise.

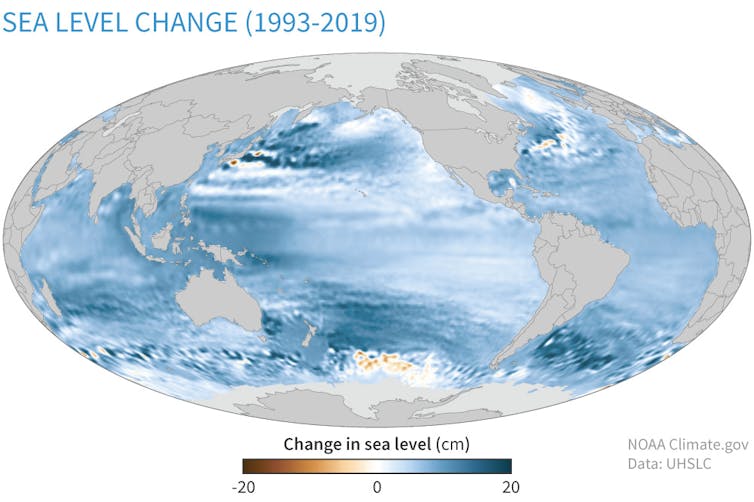

While the surface height of the ocean is rising globally, the impact is not the same for every coastal region on Earth. The rate of rise can be several times faster in some places than others. This difference is caused by an area’s unique local conditions – such as shifts in ocean circulation and the uplift or subsidence of the land.

The people of Kiribati, a small island nation in the South Pacific

Ocean, have been grappling for years with the impacts of rising seas

driven by climate change, although they’ve done very little to contribute

to global carbon pollution. Jonas Gratzer/Getty Images

The risks will keep rising long after emissions stabilize

Ocean, have been grappling for years with the impacts of rising seas

driven by climate change, although they’ve done very little to contribute

to global carbon pollution. Jonas Gratzer/Getty Images

Nearly 4 in 10 U.S. residents live near a coastline, and millions of people are already dealing with coastal flooding during hurricanes and high tides that can damage homes, buildings and other coastal infrastructure and ecosystems.

The Chesapeake Bay area was hit with flooding during high tides in late October, and the Miami area now deals with high-tide flooding several times a year.

Worldwide, researchers have estimated that sea level rise this century could cause trillions of dollars in damage. In some low-lying island nations, including the Maldives in the Indian Ocean and Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean, rising seas are already forcing citizens to make stark choices about building costly ocean protections that will only last so long or plan to abandon their islands.

Even when emissions come down, sea level will keep rising for centuries because the massive ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica will continue to melt and take a very long time to reach a new equilibrium.

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change shows the excess heat already in the climate system has locked in the current rates of thermal expansion and land ice melt for at least the next few decades.![]()

Jianjun Yin, Associate Professor of Geoscience, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.