By Robert Reich

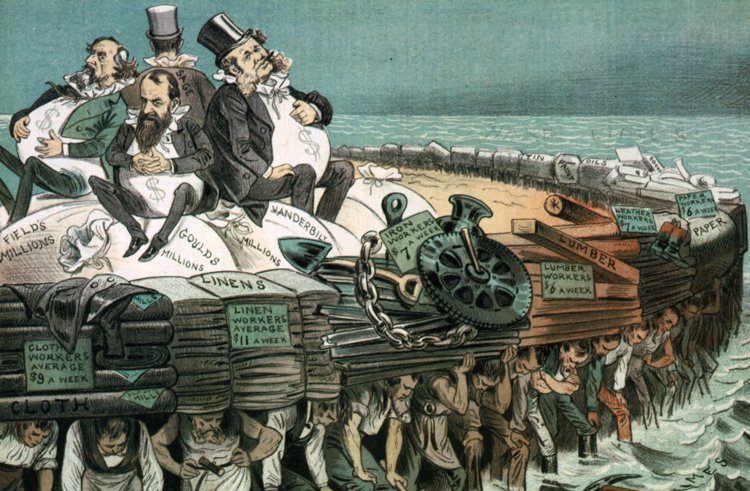

The biggest culprit for rising prices that’s not being talked about is the increasing economic concentration of the American economy in the hands of a relative few giant big corporations with the power to raise prices.

If markets were competitive, companies would seek to keep

their prices down in order to maintain customer loyalty and demand. When the

prices of their supplies rose, they’d cut their profits before they raised

prices to their customers, for fear that otherwise a competitor would grab

those customers away.

But strange enough, this isn’t happening. In fact, even in

the face of supply constraints, corporations are raking in record

profits. More than 80 percent of big (S&P 500) companies that have

reported results this season have topped analysts’ earnings forecasts,

according to Refinitiv.

Obviously, supply constraints have not eroded these profits.

Corporations are simply passing the added costs on to their customers. Many are

raising their prices even further, and pocketing even more.

How can this be? For a simple and obvious reason: Most don’t

have to worry about competitors grabbing their customers away. They have so

much market power they can relax and continue to rake in big money.

The underlying structural problem isn’t that government is

over-stimulating the economy. It’s that big corporations are under competitive.

Corporations are using the excuse of

inflation to raise prices and make fatter profits. The result is a transfer of

wealth from consumers to corporate executives and major investors.

This has nothing to do with inflation, folks. It has

everything to do with the concentration of market power in a relatively few

hands.

It’s called “oligopoly,” where two or three companies

roughly coordinate their prices and output.

Judd Legum provides some good examples in his newsletter. He points to two firms that are giants in household staples: Procter & Gamble and Kimberly Clark.

In April, Procter

& Gamble announced it would start charging more for everything from diapers

to toilet paper, citing “rising costs for raw materials, such as resin and

pulp, and higher expenses to transport goods.”

Baloney. P&G is raking in huge profits. In the quarter

ending September 30, after some of its price increases went into effect, it

reported a whopping 24.7% profit margin. Oh, and it spent $3 billion in the

quarter buying its own stock.

How can this be? Because P&G faces very little

competition. According to a report released this month from the Roosevelt

Institute, “The lion’s share of the market for diapers,” for example, “is

controlled by just two companies (P&G and Kimberly-Clark), limiting

competition for cheaper options.”

So it wasn’t exactly a coincidence that Kimberly-Clark announced similar price increases at the same time

as P&G. Both corporations are doing wonderfully well. But American

consumers are paying more.

Or consider another major consumer product oligopoly:

PepsiCo (the parent company of Frito-Lay, Gatorade, Quaker, Tropicana, and

other brands), and Coca Cola. In April, PepsiCo announced it was

increasing prices, blaming “higher costs for some ingredients, freight and labor."

Rubbish. The company recorded $3 billion in operating profits and increased its

projections for the rest of the year, and expects to send $5.8 billion in

dividends to shareholders in 2021.

If PepsiCo faced tough competition it could never have

gotten away with this. But it doesn’t. In fact, it appears to have colluded

with its chief competitor, Coca-Cola – which, oddly, announced price increases

at about the same time as PepsiCo, and has increased its profit margins to 28.9%.

And on it goes around the entire consumer sector of the

American economy.

You can see a similar pattern in energy prices. Once it

became clear that demand was growing, energy producers could have quickly

ramped up production to create more supply. But they didn’t.

Why not? Industry experts say oil and gas companies

(and their CEOs and major investors) saw bigger money in letting prices run higher before producing more

supply.

They can get away with this because big oil and gas

producers don’t face much competition. They’re powerful oligopolies.

Again, inflation isn’t driving most of these price

increases. Corporate power is driving them.

Since the 1980s, when the federal government all but

abandoned antitrust enforcement, two-thirds of all American industries have

become more concentrated.

Monsanto now sets the prices for most of the nation’s seed

corn.

The government green-lighted Wall Street’s consolidation

into five giant banks, of which JPMorgan is the largest.

It okayed airline mergers, bringing the total number of

American carriers down from twelve in 1980 to four today, which now control 80

percent of domestic seating capacity.

It let Boeing and McDonnell Douglas merge, leaving America

with just one major producer of civilian aircraft, Boeing.

Three giant cable companies dominate broadband [Comcast,

AT&T, Verizon].

A handful of drug companies control the pharmaceutical industry

[Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck].

So what’s the appropriate response to the latest round of

inflation? The Federal Reserve has signaled it won’t raise interest rates for

the time being, believing that the inflation is being driven by temporary

supply bottlenecks.

Meanwhile, Biden Administration officials have been consulting with the oil industry in an

effort to stem rising gas prices, trying to make it simpler to issue commercial

driver’s licenses (to help reduce the shortage of truck drivers), and seeking

to unclog over-crowded container ports.

But none of this responds to the deeper structural issue –

of which price inflation is symptom: the increasing consolidation of the

economy in a relative handful of big corporations with enough power to raise

prices and increase profits.

This structural problem is amenable to only one thing: the

aggressive use of antitrust law.

Robert Reich's writes at

robertreich.substack.com. His latest book is "THE SYSTEM: Who Rigged It,

How To Fix It." He is Chancellor's Professor of Public Policy at the

University of California at Berkeley and Senior Fellow at the Blum Center. He

served as Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration, for which Time

Magazine named him one of the 10 most effective cabinet secretaries of the

twentieth century. He has written 17 other books, including the best sellers

"Aftershock," "The Work of Nations," "Beyond

Outrage," and "The Common Good." He is a founding editor of the

American Prospect magazine, founder of Inequality Media, a member of the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and co-creator of the award-winning documentaries

"Inequality For All," streaming on YouTube, and "Saving

Capitalism," now streaming on Netflix.