A better estimate for tick numbers with ‘citizen science’ data

Katherine Unger Baillie, Penn State University

Apps and websites like eBird and iNaturalist encourage members of the

public to report their observations on everything from songbird migration

patterns to the presence of new planets. The result is massive datasets that

far outmatch what professionally trained scientists could collect, at least in

terms of quantity. However biases in the quality of data collected by “citizen

scientists” sometimes prevent it from being used to address foundational

scientific questions.

A new study led by Tam Tran, who earned her doctoral degree working with Dustin Brisson of Penn’s Department of Biology in the School of Arts & Sciences, taps into this wealth of citizen science data, identifying a strategy for correcting its biases to increase its value to science.

Tran and colleagues

applied this method to a large dataset documenting Ixodes scapularis,

the black-legged tick, the vector of Lyme disease. The result is the most

comprehensive look to date at the tick’s distribution across the northeastern

United States.

They shared their findings in

the Journal of the

Royal Society Interface.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Why a tick article in December? You CAN get bitten by a tick in the winter even at temperatures at or below freezing. And especially during a thaw. It's a weird feeling to have a tick crawling on the back of your hand while there is snow on the ground, but it happens. = Will Collette

“Normally with citizen science data you can validate it by controlling for characteristics that describe the collector: their level of education, their experience collecting, and so on,” says Tran, who is now completing her medical degree at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“But we

didn’t have that data. Instead we found we could use county-level data on

demographics and a few other factors to successfully correct the biases in this

data. Doing that, we were able to create currently the most updated map of tick

abundance across the Northeast.”

The new tick maps could help guide

efforts to raise awareness about Lyme disease risks and the importance of

checking for ticks after spending time in areas of tick habitat.

“This was a brilliant project idea

hatched by two clever graduate students during a poster session at an

international conference,” says Brisson. “Combining data collected by the

public with scientifically collected data into statistical models has allowed

them to identify and correct collection biases and to harness the wealth of data

collected by anyone to address scientifically important hypotheses.”

Tran, as a clinician-scientist in

training, is interested in how alterations in the environment, such as climate

change, may impact health. She joined Brisson’s lab, which focuses in part on

the ecology and evolution of Lyme disease, in order to pursue these questions

focused on the effect of climate change on tick-borne diseases.

Brisson’s lab frequently

collaborates with scientists from the New York State

Department of Health (NYSDOH) who have been collecting

black-legged ticks for nearly two decades, tracking an expansion in geographic

range that has occurred during that time frame. Their active surveillance

program has collected more than 85,000 ticks across the state.

At a conference in Scotland in 2018, Tran found out about a service based at Northern Arizona University and supported by the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, through which citizen scientists could submit ticks to be identified and tested for the presence of pathogens.

Over four years (2016 – 2019), this program received more than 20,000 ticks from 49 U.S. states and Puerto Rico, a more than six-fold increase over the program’s initial estimates of the number of ticks they would receive.

Researchers including Daniel J. Salkeld of Colorado State University and W. Tanner Porter,

who is currently with Translational

Genomics Research Institute, both authors on the current work, published findings using

that data documenting the presence of ticks capable of carrying Lyme and other

tick-borne diseases in 83 counties (in 24 states) where these ticks had not

been previously recorded.

While there were rough correlations between the NYSDOH data and the citizen science data from New York, Tran and colleagues saw an opportunity to determine how to account and correct for biases within the latter dataset.

Because data about individual collectors was

limited, aside from their county of residence, the researchers used publicly

available data from Census records on county-level variables, including median

household income, population size, poverty level, race, education, and age

distribution, each of which has been correlated with Lyme disease risk.

To account for familiarity with Lyme

disease, the researchers factored in the incidence of Lyme disease in the

county and Google search trends, that is, the frequency of searches for “Lyme

disease.” Finally, they included a modifier for the mean annual temperature of

each county, as a proxy for how likely it would be for a collector to be out in

nature, a variable that would increase the likelihood of finding a tick.

Accounting for these variables, some

of which were associated with over-counting and others with under-counting

ticks, “made the citizen science data align so much better with the New York

State Department of Health data,” says Tran.

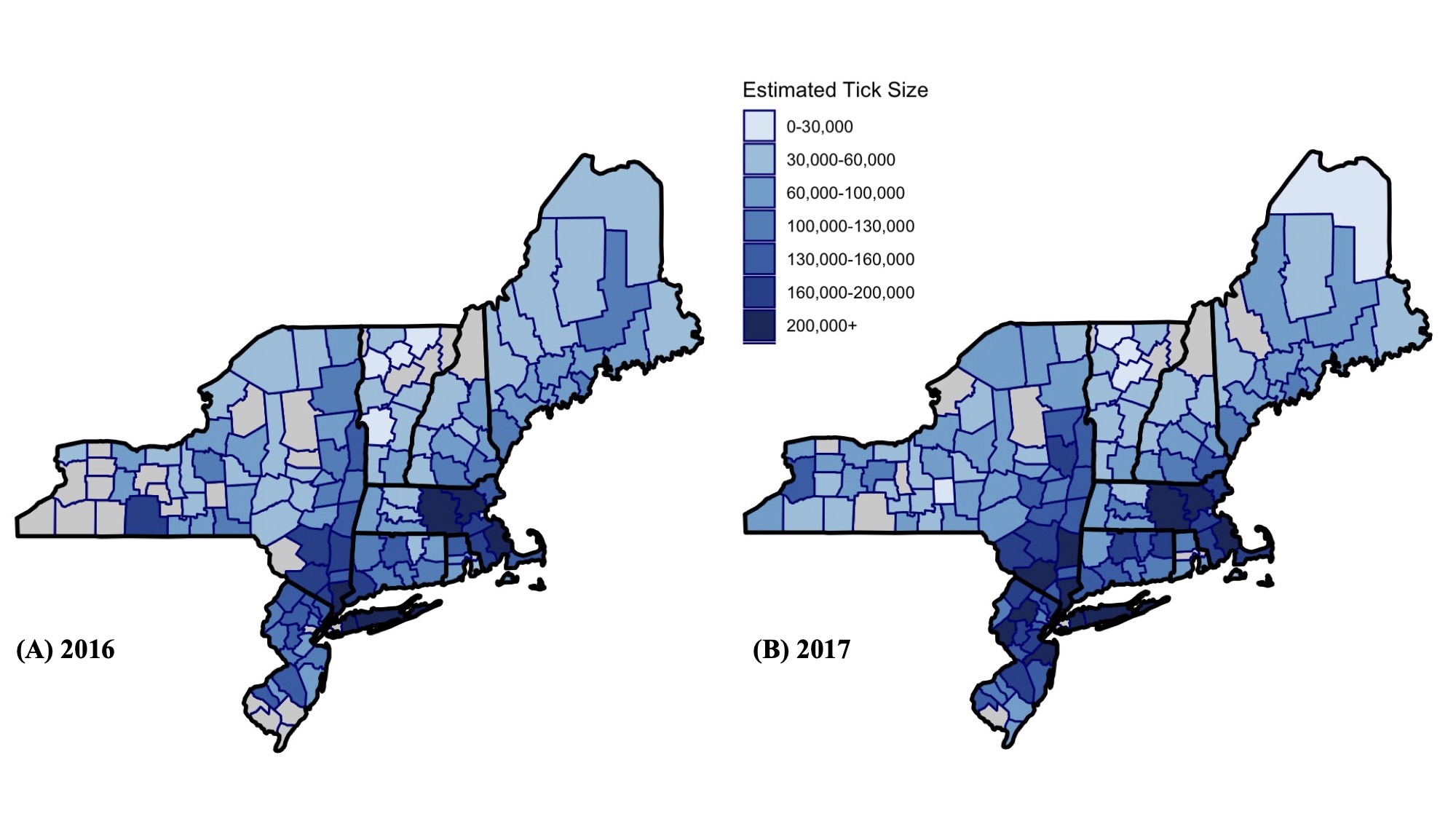

Extending their model to the whole

of the northeastern U. S., the researchers developed a map of tick population

per county that is the most robust to date.

“This is a predictor of tick

abundance from Maine down to New Jersey, validated with the incredible active

surveillance data from New York,” Tran says. “It’s an exciting way to address

big scientific questions that overcomes the limitations that sometimes get in

the way of doing professional science at this scale, like time, money, and

geographic location.”

With the U.S. Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention noting a rapidly growing

incidence of tick-borne diseases, Tran says data collected by

member of the public can help predict where Lyme disease is most likely to

impact residents.

“It’s a way to use citizen science

that we haven’t seen before,” she says.

Tam Tran earned

a Ph.D. from the University of

Pennsylvania School of Arts

& Sciences’ Department of Biology.

She is currently an M.D. student at Virginia

Commonwealth University.

Dustin Brisson is

a professor in Penn’s Department of

Biology in the School of Arts & Sciences.