These people are definitely not like us

By Paul Kiel, Jesse Eisinger and Jeff Ernsthausen for ProPublica

The sport’s royalty, including the billionaire owners of thoroughbreds, was well represented. Basking in the glory of their racehorses’ appearance on the most prestigious stage in the world, they knew all but one of them would see their colt or filly suffer defeat. A victory would bring not only a seven-figure purse, but possibly also tens of millions of dollars in breeding rights over years to come.

Even if their horses finished far out of the money, some owners had a salve for the sting of defeat: tax write-offs. Six of the 20 thoroughbreds selected to run in this year’s Derby were owned by ultrawealthy Americans whose horse-racing operations have produced a combined $600 million in losses that they could use to offset their federal taxable income, according to ProPublica’s analysis of IRS data.

Among them was Paul Fireman, who made his fortune by turning the shoe company Reebok into a household name before selling it to Adidas in 2005 for $3.8 billion. Fireman was new to the endeavor, but he’d already spent millions building a professional horse-racing operation, including dropping almost $1 million on a single thoroughbred, a descendant of a Preakness winner. His horse, King Fury, was scratched from the Kentucky Derby after spiking a fever.

Charlotte Weber, a Campbell Soup heiress who Forbes says is worth $1.6 billion, saw her appropriately named horse Soup and Sandwich break well from the outside before faltering with a breathing issue and finishing last. Brad Kelley, who made his money selling his tobacco company two decades ago and is worth $2.7 billion, owned Bourbonic, who finished 13th. Hedge fund manager Seth Klarman, worth $1.5 billion, entered a horse named Highly Motivated that would place 10th.

The tax records obtained by ProPublica shed light on how much each of these owners was able to write off. Over 16 years, Kelley claimed $189 million in losses for his racing business; Weber claimed $173 million in 21 years, and Klarman $138 million over 19 years. Fireman, a relative newcomer to the game, had taken only $9.3 million in losses as of 2018. (Kelley and Weber did not respond to requests seeking comment. Klarman, who has donated to ProPublica in the past, declined to comment.)

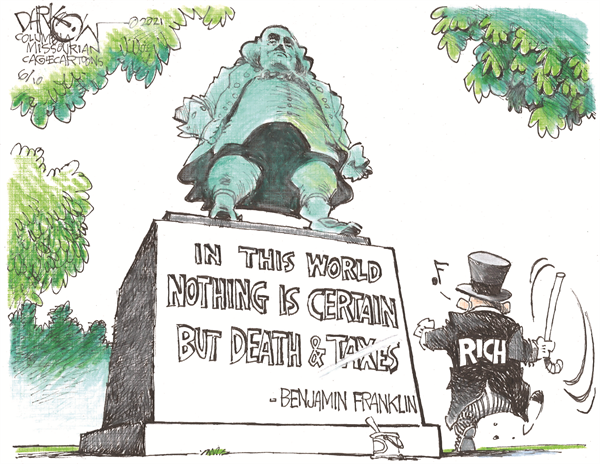

All Americans are entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. But the happiness of the wealthy can come with an added bonus: It’s subsidized by taxpayers. Billionaires can not only deduct the costs of buying, owning and training thoroughbred horses, but they can treat all manner of pastimes and side pursuits as businesses, and then tap those businesses as an extra source of deductions. By contrast, if you’re a middle-class person with a passion for thoroughbreds and you attend the Kentucky Derby, neither the money you spend on your ticket to sit in the grandstand nor, say, the $20 you blow in bets would help you lower the taxes you owe on your wages.

A trove of tax data obtained by ProPublica reveals for the first time the extent to which tax breaks underwrite the enjoyment of our richest citizens. Yesterday, ProPublica examined a special class of superrich taxpayers we called the biggest losers, who amass deductions to such an extent that they can avoid income taxes for years on end. We showed that many of these tax avoiders are titans in commercial real estate or oil and gas, industries on which the tax laws bestow unusually lucrative advantages.

Today we’re focusing on a broader set of strategies the ultrawealthy use to pile up deductions. Tax records show these loss producers go beyond the classic hobbies and encompass all sorts of businesses the rich control.

Sometimes, they plow funds into pet projects that lose money so consistently that it suggests profitability isn’t the main goal. The wealthy may not start these businesses chiefly as a way to reduce taxes — many billionaires would happily race horses even without a tax payoff — but the benefits flow in just the same.

In some cases, the deductions from money-losing businesses have allowed a handful of people to avoid paying taxes for years. Ty Warner, creator of the Beanie Baby toy, lost so much money on his side business — luxury hotels and resorts — that he went 12 years without paying a dollar in federal income taxes. Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, who built his $7.1 billion fortune by selling two drug companies, oversees an array of businesses that have produced tax losses, including the Los Angeles Times, which he bought in 2018. He hasn’t paid federal income tax in five consecutive recent years.

These feats are possible because the U.S. tax system has made it easy for the ultrawealthy to harvest business deductions without limit. There are rules they must navigate, the result of almost 80 years of congressional efforts to rein in what lawmakers viewed as abuses. These rules include limits on the deductibility of hobbies and provisions to discourage investments that produce tax-reducing losses year after year. But these measures have proven far more effective at preventing the merely affluent from deducting losses than they have at stopping the ultrawealthy from doing so.

“The rules are like penicillin: It’s still effective sometimes, but there are some people who are resistant,” says Brian Galle, a former tax prosecutor who teaches tax law at Georgetown. “The well-advised, wealthy individuals have figured out ways around them.”

In the early 1940s, Congress made its first strong bid to stop the wealthy from claiming endless deductions from their personal businesses. The law came in the wake of widely publicized congressional hearings in 1937 that focused, in part, on tax avoidance through horse breeding and racing. Lawmakers targeted Marshall Field, the wealthy department store operator, because he had taken substantial tax deductions on his money-losing newspapers. (Conservatives pushed that effort, upset with the left-wing bent of Field’s Chicago papers.)

The line drawn was simple: After five straight years of losses, further tax deductions would be sharply limited. A real business exists to make money, the lawmakers reasoned, and after a certain point, it’s obvious that profit isn’t the point.

But the five-year rule was easily gamed — four years of huge losses and one year of tiny profit did the trick — and eventually it was dropped. Congress decided on a more subjective approach. In 1969, a new law took aim more specifically at “hobby losses.” That law is largely intact today.

Under the hobby loss rule, a pursuit is defined as either a hobby or a for-profit endeavor. To qualify as a bona fide business, an activity needn’t actually turn a profit. “It does not matter that profitability is improbable, it just has to be sincerely pursued,” as one accountant, Peter Reilly,put it.

Taxpayers decide for themselves whether they are engaged in a hobby. Only if they are audited will that decision be questioned, and to disallow any iffy deductions, the IRS must engage in a complex act of mind-reading. Using a nine-factor set of guidelines (including “elements of personal pleasure or recreation” and “the expertise of the taxpayer or his or her advisers”) the agency must establish that a taxpayer is not engaged in a genuine attempt to make money.

When an activity turns a profit in three of five years, the odds shift even further in the taxpayer’s favor. Then the IRS must presume it’s a genuine business and the agency bears the burden of proving otherwise. The standard is actually more lenient for taxpayers involved in the very activity that spurred authorities to crack down in the first place: horse racing. There, showing profit in two of seven years is enough to shift the burden of proof.

Despite these obstacles, the IRS often wins the few audits that make it to court — but those victories come far more easily in smaller cases.

For the ultrawealthy, it’s easier to clear the IRS’ hurdles. Tax professionals advise clients that they can be bold in taking losses, as long as they take some careful steps first: The business should generate some revenue and the books should be kept by professionals. In horse racing, a whole system of consultants, trainers and jockeys are ready to turn a hobby into a professional venture for the ultrawealthy. And race purses, even if victories are rare, provide revenue.

ProPublica found plenty of examples of billionaires who appear undaunted by the hobby loss rule. The tax records of both Kelley, the tobacco billionaire, and Weber, the soup heiress, show losses for at least 16 straight years, with their horse racing entities never once turning a profit. Other owners of horses in the Derby showed similar streaks.

The IRS’ inspector general has repeatedly faulted the agency for not being aggressive enough in enforcing the rule. In its most recent effort in 2016, the office wrote that the agency generally fails to look for high earners who are writing off hobby losses and that even “when returns containing potential hobby losses are selected for audit, the examiners do not always address the hobby loss.”

Even if the hobby loss rule were aggressively enforced, however, it covers only one aspect of how the wealthy can use their fortunes to generate tax deductions from their businesses. ProPublica previously highlighted how they can reap large losses from buying a sports team, for instance. The ultrawealthy often sit atop a number of businesses that provide them with enormous deductions.

Fireman, for instance, has a couple of tax-losing leisure activities that have traditionally been scrutinized as possible hobbies. In addition to his horse-racing operation, he also owns the Winecup Gamble Ranch, which occupies almost a million acres, about 58 miles across, in northeast Nevada. Once owned by the actor Jimmy Stewart, Winecup Gamble says on its website that it’s “devoted to being a profitable cattle ranching operation.” But from 2003 through 2018, it delivered $22 million in tax losses to Fireman without a single year of profit.

Fireman hasn’t spent all his time on horse racing and cattle ranching. He also used his fortune to launch upscale real estate projects, including golf courses, as well as a country club and a residential development on Cape Cod. These have allowed him to tap into the tax benefits enjoyed by real estate professionals.

From 2008 through 2017, because of the deductions from his various businesses, Fireman was able to entirely offset $360 million in income. He paid nothing in federal income taxes in eight of those years.

Fireman declined to comment.

In theory, there’s a limit to how many businesses an ultrawealthy person can reap massive deductions from. Taxpayers can use their businesses’ losses to offset all other kinds of income only if they “materially” participate in the company. They must play a key role running the business.

Of course, just as with hobbies, this is subjective, and to decide the matter, the tax code has another set of conditions (this time there are seven). The clearest requirement is that the taxpayer spend at least 500 hours on the activity during the year. Since 40-hour weeks add up to around 2,000 working hours in a year, a taxpayer could theoretically actively run only four businesses, or perhaps one or two more if they put in longer hours.

Yet some taxpayers have far more. With Patrick Soon-Shiong, the 89th-wealthiest American, it’s hard to keep track.

The billionaire is far from passing his retirement quietly. In 2016, he announced an ambitious initiative to revolutionize the hunt for a cancer cure, entitled the “Cancer Moonshot 2020.” In 2018, like Marshall Field before him, he bought newspapers, in Soon-Shiong’s case, the Los Angeles Times and The San Diego Union-Tribune.

More recently, he’s been holed up in his compound, according to a New Yorker profile, overseeing an effort to find an innovative vaccine for COVID-19. That article explored his working on finding cancer cures, developing vaccines and saving newspapers, but also raised questions about his financial dealings. Soon-Shiong defended his conduct as appropriate in the article.

Soon-Shiong is pursuing many other business endeavors. He continues to own biotech companies. He also owns a health care information effort, a zinc-air battery developer, a bioplastics operation, a water purification company, a production soundstage and an urban scooter offering, among other outfits.

These businesses have provided write-offs that have canceled out the $887 million in income, most of that from interest, dividends and capital gains, that Soon-Shiong has received since 2013, letting him report huge losses to the IRS.

Some of the write-offs come in bulk, as in 2018, when he received a $178 million loss from the entity that houses his newspapers. Other businesses have dribbled out tens of millions in losses over a series of years.

Soon-Shiong reported negative income for six straight years from 2013 through 2018. That enabled the billionaire doctor to pay no federal income tax from 2013 through 2017. In 2018, he paid $158,000. By the end of 2018, he still had over $400 million in accumulated losses that he could use to offset income in future years, ProPublica estimates.

Soon-Shiong did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

If Soon-Shiong was not “materially” participating in his businesses, his ability to offset other types of income would be curtailed. Losses from “passive” activity, as the tax code puts it, can be used to offset only other passive business income. That would prevent Soon-Shiong from, say, using passive business losses to offset his wages or personal investment income.

The ProPublica tax records don’t make clear which specific business lines Soon-Shiong materially participated in. But the vast majority of his losses were not passive.

In reality, no hard ceiling exists on how many businesses an ultrawealthy person can claim to actively run. One way around the “material participation” rule is to argue that what appear to be a number of separate businesses are actually all aspects of a single activity. In Soon-Shiong’s case, many of his businesses, even though they are discrete operations in different sectors, are organized under a holding company. To decide what’s an appropriate “grouping” of businesses, the tax code offers another multifactor (it’s five this time) test. Because the test is “quite flexible in how it applies,” said William Kostak, a former IRS attorney, “for the IRS to raise that issue would be an uphill battle.” That means taxpayers can be bold in claiming deductions from an array of businesses.

If average Americans wanted to invest in such a variety of businesses, they’d have to buy shares in mutual funds or a bunch of stocks. When such investments result in net losses, the deductions are sharply limited. They can be used to offset no more than $3,000 a year in wages and other noninvestment income.

As Soon-Shiong waited for one of his startups to strike gold, the losses on many of his businesses were deductible on his taxes, without being subject to such limits. And, as ProPublica has shown in other articles in this series, if one of his businesses hits it big, he’ll have all sorts of mechanisms he can use to avoid taxes. Either way, the government may get nothing.

Business moguls Ty Warner and Kevin Kalkhoven have learned through painful experience how to — and how not to — avoid the taxman legally. Early in their existences as multimillionaires, each tried a strategy that would later land them in trouble.

For Warner, it started with a Swiss bank account, which he opened in 1996, just as Beanie Baby mania was beginning to hit. Such accounts are legal, but only if they’re reported to the IRS. Warner didn’t report the account, whose balance eventually exceeded $100 million. When the bank agreed to disclose its American customers, Warner moved his money to another Swiss bank and put it in the name of a fake Liechtenstein charity. In 2013, he pleaded guilty to evading about $6 million in taxes between 1996 and 2007. Warner was fined $54 million and sentenced to two years’ probation (despite prosecutors’ requests that he serve time in jail).

For Kalkhoven, the trouble stemmed from tax shelters. He made his fortune as CEO of the onetime stock darling JDS Uniphase, a telecom equipment concern whose stock was crushed, not long after he departed, in the dot-com crash of 2000. Kalkhoven used a kind of shelter that the government eventually deemed to be fraudulent. A federal court would later determine that Kalkhoven and his fellow participants in one shelter invested $16.5 million and got nearly 20 times that investment — $3.1 billion — in artificial losses in return. Major accountingfirms were criminally prosecuted, but Kalkhoven was not charged with any wrongdoing.

Kalkhoven has maintained that he relied on advice from his accountants. His lawyer did not respond to a detailed list of questions for this story.

In 2004, the IRS began auditing his 2000 and 2001 returns and eventually sought money back from him over the shelters. That battle continues today.

Even as the consequences of these early steps slowly unfurled, Kalkhoven and Warner became adept at legal tax avoidance.

Warner’s biggest success at limiting his taxes began in 1999, the same year he made his debut on Forbes’ list of wealthiest Americans. That’s when he bought the Four Seasons hotel in midtown Manhattan for $275 million. Next came the Four Seasons in Santa Barbara for $150 million. His luxury portfolio grew from there: exclusive resorts, country clubs and golf courses.

Warner’s new side gig as an upscale developer provided him with a range of benefits. There was, of course, the glamour of owning landmark properties, hosting celebrities and presiding over galas. Warner wanted his properties to recapture a lost, opulent past. When, in 2008, after extensive renovations, he reopened the Coral Casino Beach and Cabana Club (memberships started at $250,000) across the street from his Santa Barbara Four Seasons, Warner saluted the time when Marlon Brando and Errol Flynn were regulars there. Legendary for his obsessive involvement in every detail of Beanie Babies, Warner became similarly fixated on his luxury properties. At one hotel, he invented the swimming pool’s iridescent tiles, which he called “tyles,” a play on his first name.

Then, of course, there were the tax advantages. Warner took out huge loans against his properties, then deducted the interest costs. He also wrote off his purchases and renovations over time, using deductions for depreciation that treat the properties as losing value for tax purposes even if they gained value in the real world. Those deductions were so large that they offset the income spun off by his properties, his profitable toy business and his personal investments.

Warner’s tax records show that the Santa Barbara Four Seasons, the focus of his most extensive renovations, lost money in 16 of the 18 years between 2002 and 2019. But those losses provided a huge tax boon for Warner: a total of $219 million in deductions during that period.

For 12 consecutive years starting in 2004, Warner paid nothing in federal income tax, as the deductions from his luxury properties helped to offset about $363 million in income. In more recent years, the increasing profitability of Warner’s toy company finally pushed him into the black on his tax returns. From 2016 through 2018, Ty Inc. sent a total of $228 million to Warner, but even that wasn’t enough to result in a significant tax burden for the billionaire. In total, Warner paid less than $1 million in income tax over the three years.

Representatives for Warner, who is worth about $4.5 billion, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

For his part, Kalkhoven learned to take deft advantage of money-losing side businesses similar to horse racing, though he preferred cars and airplanes to thoroughbreds. Kalkhoven became one of the owners of the ChampCar league and founded an auto racing team that would go on to win the Indianapolis 500. In 2004, he purchased a high-tech auto parts company called Cosworth.

He also owned companies whose main assets were his jets. Kalkhoven would joke about living in the ZIP code of “N-one-four-four-kilo-kilo,” the tail numbers of his Gulfstream. (He liked to trade them in every few years.) On board, according to Racer magazine, he hosted junkets for journalists where he served “Moscow martinis” — a thumbful of caviar washed down with vodka.

His car-racing team, his auto-parts company and his aviation operation all helped produce losses for tax purposes.

In 2005, Kalkhoven began a remarkable streak of losing money. From that year through 2018, he reported losses in 13 of 14 years. He paid federal income taxes in only two of those years, and even then he paid just about $422,000, according to ProPublica’s data. In that time, he brought in $264 million, mostly in capital gains and interest income.

As this was happening, the IRS case stemming from Kalhkoven’s turn-of-the-millennium tax shelters was making glacial progress. It reached a critical point this summer when the agency took the unusual step of freezing his assets, which Kalkhoven has decried and is fighting in court. The agency is seeking $350 million in back taxes, interest and penalties.

The federal government recently argued in court that it had to take the drastic step of freezing Kalkhoven’s assets because he appeared to be on the brink of insolvency. Government lawyers pointed out that “he now appears nearly broke in the United States: he has paid no significant federal income tax for over 15 years and has even claimed the recent federal stimulus meant for individuals struggling during the pandemic.”

The prosecutors’ move forced Kalkhoven’s lawyers to argue that, whatever their client’s tax returns might show, Kalkhoven was not on the verge of going belly up. The executive’s lawyer said just one of Kalkhoven’s assets was “large enough by itself to put to rest any speculation that Mr. Kalkhoven’s financial situation was imperiled.” It was silly to think, the statement seemed to suggest, that not paying taxes for a decade means a person has no money.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.