Alex

Nunes, The Public's Radio

Late

last year, former Narragansett Indian Tribe First Councilman Randy Noka stood

in a clearing on 32 acres of land in the Charlestown woods. He said if you want

to know what he thinks of the town and its solicitor for Indian affairs, visit

this spot where 12 small homes remain abandoned. The

property was supposed to be affordable housing for elderly members of the

tribe. Today, you see overgrown grass and buildings with smashed in windows.

For Noka, it’s heartbreaking. “You

can see the condition of them,” Noka said. “It's a deplorable condition. And

just as bad, if not worse, is the reason why.” The

details of this case may sound familiar. The property was at the heart of a

years-long jurisdictional battle between the tribe and the town and state that

went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Ultimately, a majority of justices

ruled against the tribe’s effort to place the land in federal trust and beyond

local and state laws, finding that the Narragansetts didn’t qualify because the

tribe wasn’t federally recognized in 1934 when a U.S. law outlined trust

rules. After

the ruling, Charlestown still wouldn’t allow the housing project to be

completed through its approval process, because the Narragansetts wouldn’t sign

away sovereign immunity shielding them from legal action should they someday

decide to build something else on the land. “So

they let this happen,” Noka said of town officials. “It never did go into trust

and maybe never will. But you could have allowed the project to go forward, let

the tribe finish it, let the private landowner–don't even have to put the tribe

there for the sake of an example–let the private landowner move forward.

There's projects all over this place.” The

attorney at the center of the legal dispute on the town’s behalf was Joe

Larisa. The Narragansett Indian Tribe has its headquarters and about 1,800

acres in Charlestown, more land than anywhere else in the state. And Larisa has

been around for nearly two decades as the town’s solicitor for Indian

affairs. Larisa

defends his position, saying in an interview that the job is about “facing the

reality that we're the only town with a sovereign nation within our

borders.” He

continued, “Because of that, the town needs to be aware of its legal rights on

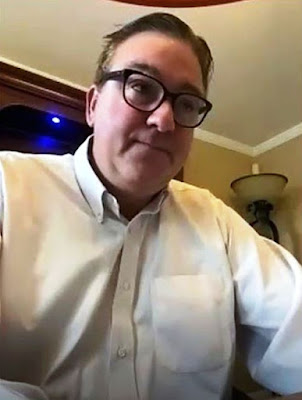

every matter involving the tribe.” 👈 Charlestown Solicitor for Indian Affairs Joe Larisa is pictured in a video interview. Larisa

got his start opposing the tribe at the state level, working against a

potential Narragansett casino in the 1990s and early 2000s for two separate

governors. In

Charlestown, he’s worked on civil rights cases involving town police and tribal

members, issues stemming from the state’s infamous raid on a tax-free

Narragansett smoke shop, and a more recent land transfer from the state to the

tribe that fell through because of disagreements over tribal rights related to

the land. Larisa also represents a public library in

Jamestown that wants to build on land the Narragansetts say is a sacred burial

site. “He's

solicitor for Indian affairs issues, or fight-the-Narragansett-Tribe issues,”

Randy Noka said. “To put it in my own words: ‘Any Indian that isn't benefiting

because he's Indian, because he's Narragansett–any rights the Narragansett

don't get because here I am, the Great Indian Slayer Joe Larisa, then good for

me, good for the town of Charlestown.’" In

the last year, some town leaders have raised questions about Larisa’s

arrangement with Charlestown. Town Council President Deb Carney is one of two

council members who voted against renewing his contract in 2021. “What

we’re doing is we're retaining an attorney specifically against a group of

people, and I don't think that's right,” Carney said. “We don't do that, nor

should we do that, with any other group.” Carney

and the other councilor who voted no, Grace Klinger, questioned the expense of

Larisa’s contract. Currently, Larisa gets a retainer of $2,000 dollars a month

regardless of how much work he does, plus $130 dollars an hour for additional

litigation work. Carney takes her criticism a step further. She says Larisa’s

position, as it’s currently structured, is “a bit racist.” “We’re

discriminating against one group of people,” she said. “We've separated the

Narragansetts and said, ‘We're going to keep somebody on retainer just for

every issue involving them.’” Town

Councilor Bonnie Van Slyke disagrees with that. Van Slyke, joined by council

members Cody Clarkin and Susan Cooper, approved Larisa’s contract. She says the

town solicitor for Indian affairs position is necessary and does not target the

Narragansetts. “They

are our neighbors. They're very special neighbors,” Van Slyke said. “It's a

matter of respect to understand what the basis is that we're dealing with these

various jurisdictional issues. We need consistent, up to date advice on what

these issues are and how to act, how to deal with them.” Central

to the solicitor’s position is the question of Narragansett land sovereignty

and the possibility that Congress may someday pass legislation that could

effectively nullify the 2009 Supreme Court decision and allow the Narragansetts

to place land in federal trust without restrictions. That’s why a big part of

Joe Larisa’s job is monitoring developments in Washington, D.C. and maintaining

lines of communication with the governor’s office should a change in status be

on the table. “If

the tribe gets land in federal trust, unrestricted, it'd be ‘Indian country,’”

Larisa said. “And when you have ‘Indian country,’ the land is largely exempt

from state laws, state civil laws, state criminal laws, and town ordinances. It

means they can largely do what they want, just like a sovereign nation within

our borders.” Larisa

added, “Square one is it opens the door a crack to a casino again. It could

open the door to other activities that would be illegal under town law or state

law.” But

members of the tribe say that’s fear-mongering. Narragansett

Indian Tribe Medicine Man John Brown is pictured at the tribe's farm in

Westerly.ALEX NUNES - THE PUBLIC'S RADIO

With

the amount of legal gambling in the region already, Narragansett Indian Tribe

Medicine Man John Brown says a casino isn’t even a viable business opportunity

today. He also points out that the Narragansetts own property in multiple

states, including several hundred acres in Westerly, where the tribe’s

relationship with town officials has been much more positive. Consider also

that, in Connecticut, the state’s two federally recognized tribes have land in

federal trust, and the towns they’re located in don’t have solicitors for

Indian affairs. “There's

this unnecessary fear of what we're going to do and how we're going to do it,”

Brown said. “When you look at our lands and you look at the lands around us,

it's not us that's overbuilt on our property. It's not us that’s fouled our

waters. It's not us that’s fouled the air. We are a natural people, and we

maintain the things that we have in natural or close to natural existence.” Joe

Larisa’s contract as Charlestown solicitor for Indian affairs has no end date

on it and will next come up for discussion when the town council chooses to revisit

it. So far, it has not. Alex

Nunes can be reached at anunes@thepublicsradio.org. LISTEN

to the 8-minute broadcast here: https://soundcloud.com/user-911967060/in-charlestown-critics-say-special-solicitor-position-is-discriminating-against-one-group-of-people |