Over-stimulated immune system may be impetus to cognitive symptoms, study shows

University of California - San Francisco

Some patients who develop new cognitive symptoms after a mild bout of COVID have abnormalities in their cerebrospinal fluid similar to those found in people with other infectious diseases. The finding may provide insights into how SARS-CoV-2 impacts the brain.

In

a small study with 32 adults, comprising 22 with cognitive symptoms and 10

control participants without, researchers from UC San Francisco and Weill

Cornell Medicine, New York, analyzed the cerebrospinal fluid of 17 of the

participants who consented to lumbar puncture. All participants had had COVID

but had not required hospitalization.

They

found that 10 of 13 participants with cognitive symptoms had anomalies in their

cerebrospinal fluid. But all four of the cerebrospinal samples from

participants with no post-COVID cognitive symptoms were normal. The research

publishes on Jan. 18, 2022 in Annals of Clinical and Translational

Neurology.

The

average age of the participants with cognitive symptoms was 48, versus 39 for

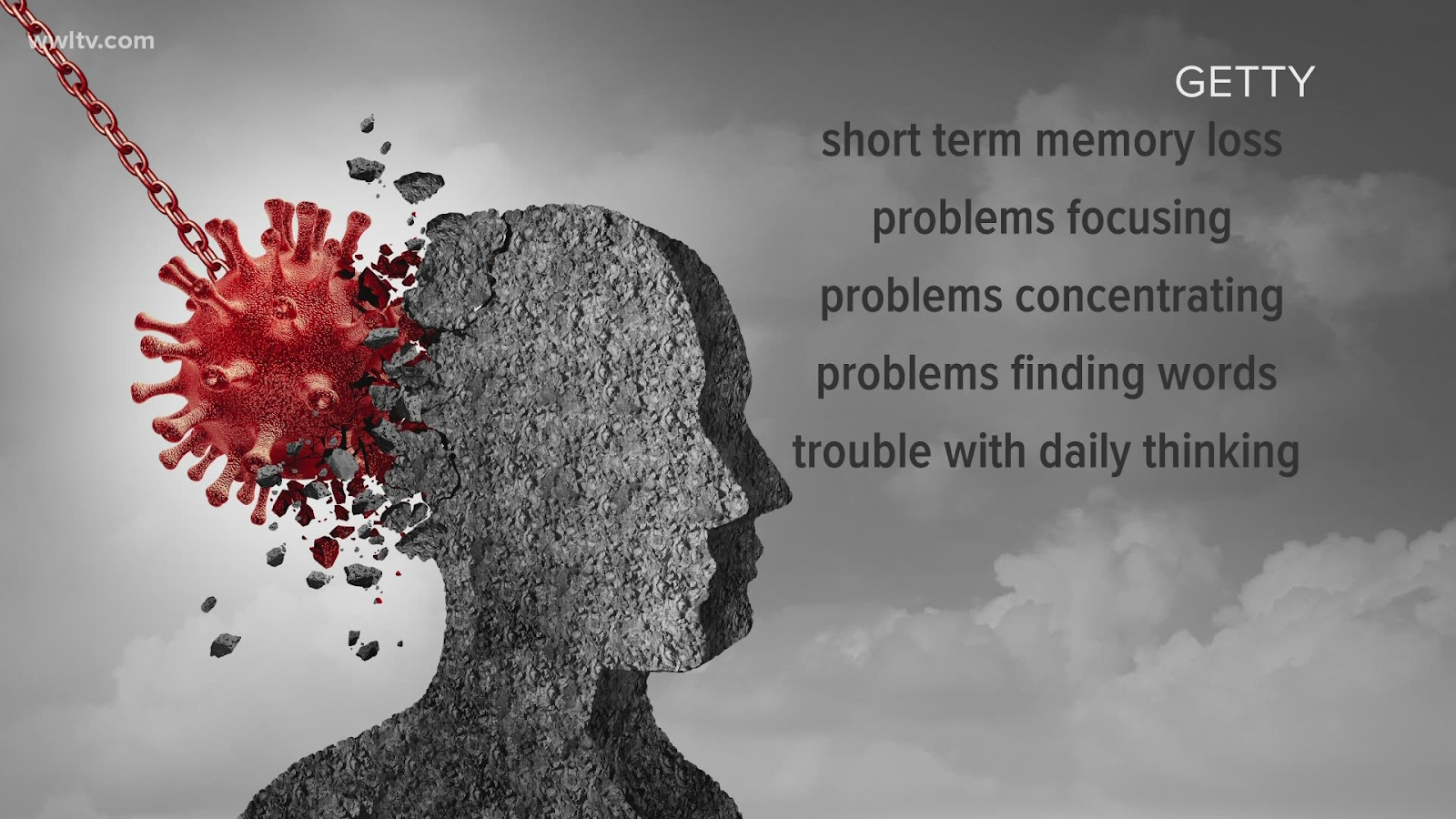

the control group. Participants with these symptoms presented with executive

functioning issues, said senior author Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS, of the UCSF

Memory and Aging Center. "They manifest as problems remembering recent

events, coming up with names or words, staying focused, and issues with holding

onto and manipulating information, as well as slowed processing speed,"

she said.

"Brain

fog" is a common after-effect of COVID, affecting some 67 percent of 156

patients at a post-COVID clinic in New York, a study published this month

shows. In the current study, patients were enrolled in the Long-term Impact of

Infection with Novel Coronavirus (LIINC) study that evaluates recovery in

adults with confirmed SARS-CoV-2.

Examinations of the cerebrospinal fluid revealed elevated levels of protein, suggesting inflammation, and the presence of unexpected antibodies found in an activated immune system. Some were found in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid, implying a systemic inflammatory response, or were unique to the cerebrospinal fluid, suggesting brain inflammation. While the targets of these antibodies are unknown, it is possible that these could be "turncoat" antibodies that attack the body itself.

Immune

System Runs Amok Months After COVID

"It's

possible that the immune system, stimulated by the virus, may be functioning in

an unintended pathological way," said Hellmuth, who is principal

investigator of the UCSF Coronavirus Neurocognitive Study and is also

affiliated with the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences. "This would be

the case even though the individuals did not have the virus in their

bodies," she said, noting that the lumbar punctures took place on average

10 months after the participants' first COVID symptom.

The

researchers also found that the participants with cognitive symptoms had an

average of 2.5 cognitive risk-factors, compared with an average of less than

one risk factor for participants without the symptoms. These risk-factors

included diabetes and hypertension, which can increase the risk of stroke, mild

cognitive impairment and vascular dementia; and a history of ADHD, which may

make the brain more vulnerable to executive functioning issues. Other risk

factors included anxiety, depression, a history of heavy alcohol or repeated

stimulant use, and learning disabilities.

Testing

May Fall Short in Diagnosing Mild Cognitive Disorders

All

participants underwent an in-person cognitive testing battery with a

neuropsychologist, applying equivalent criteria used for HIV-associated

neurocognitive disorder (HAND). Surprisingly, the researchers found that 13 of

the 22 participants (59 percent) with cognitive symptoms met HAND criteria,

compared with seven of the 10 control participants (70 percent).

"Comparing cognitive performance to normative references may not identify

true changes, particularly in those with a high pre-COVID baseline, who may

have experienced a notable drop but still fall within normal limits," said

Hellmuth.

"If

people tell us they have new thinking and memory issues, I think we should

believe them rather than require that they meet certain severity

criteria."

Cognitive

symptoms have been identified in other viruses, in addition to COVID and HIV.

These include the coronaviruses SARS and MERS, hepatitis C and Epstein-Barr

virus.

Co-Authors: First

author is Alexandra C. Apple, PhD, of the UCSF Memory and Aging Center and the

Weill Institute for Neurosciences. For a complete list of co-authors, please

refer to the paper.

Funding

and Disclosures: The research is supported by grants from the

National Institutes of Health/NIMH (K23MH114724) and the National Institutes of

Health/NINDS (R01NS118995-14S). For a full list of disclosures, please refer to

the paper.