Can't blame them

Oana Godeanu-Kenworthy, Miami University

|

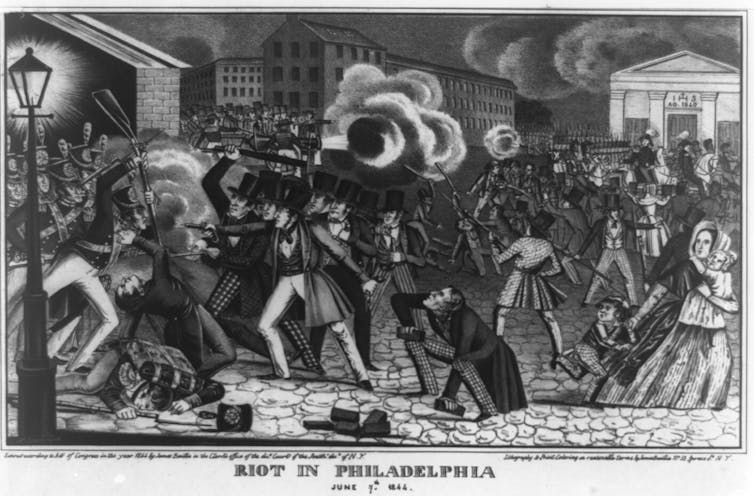

| Anti-Catholic riots, like this one in Philadelphia in 1844, worried Canadians. H. Bucholzer via Library of Congress |

That helps explain why Canadian police used emergency powers to arrest hundreds of people and tow dozens of vehicles while ending the trucker protests in Ottawa, Canada’s capital.

Since its founding, Canada has taken a very different view of liberty, democracy, government authority and individual freedom than is known in the United States.

As early as 1776, the Declaration of Independence stated that the purpose of the U.S. government was to preserve “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The Canadians chose a different course.

The 1867 British North America Act – since renamed the Constitution Act – declared that the goal of modern Canada was to pursue “Peace, Order, and good Government.”

As a scholar of North American culture, I have seen that Canadians have long feared the sort of mob rule that has always been a feature of the U.S. political landscape.

|

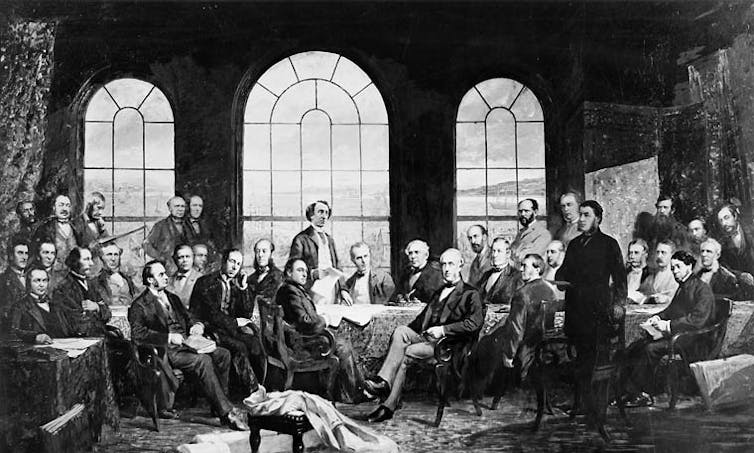

| The ‘Fathers of Confederation,’ as the founders of Canada are called, were concerned about creating a nation that might fall prey to the same problems they saw in the U.S. Photograph by James Ashfield of the Robert Harris painting 'Fathers of Confederation,' via Library and Archives Canada via Wikimedia Commons |

Casting a wary eye southward

The United States had been independent since the Revolutionary War ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. But in the mid-19th century, the provinces that make up Canada were still British colonies.

As they deliberated their future, the options seemed straightforward: a form of self-government within the British Empire and subject to the king or queen of England – or independence, possibly including absorption into the United States.

To some Canadians, the U.S. seemed a success story. It boasted a booming economy, vibrant cities, a successful westward expansion and a steadily growing population.

But to others, it provided a cautionary tale about weak central institutions and rule by the undisciplined masses.

In the early and mid-19th century, the U.S. was plagued by rampant inequality and deeply divided over race and slavery. An unprecedented wave of immigration in the 1840s and 1850s fomented social unrest because the newcomers were viewed with hostility by locals. In East Coast cities, angry mobs burned immigrants’ homes and Catholic churches.

Canadians of all classes and religious persuasions watched with anxiety the deepening societal divisions in the U.S. as the republic spiraled toward civil war. In May 1861, in an editorial for the Toronto-based newspaper The Globe, editor and politician George Brown reflected on the mood in Canada: “While we admire the devotedness to the Union of the people of the Northern United States, we are glad we are not them; we are glad that we do not belong to a country torn by [internal] divisions.”

|

| When Confederate forces fired on U.S. troops at Fort Sumter in April 1865, the Civil War began – and Canadians were concerned about their neighbor’s unstable government. Currier & Ives via Library of Congress |

Canadians and people in the United States understood the role of the government differently. U.S. institutions were created with the understanding that individual freedoms should exist separate from interference from the state.

But colonial Canadians started with the collective, not the individual. Liberty to them was not an aggregate of individual pursuits of happiness. It was the sum of the fundamental rights that a government had to guarantee and protect for its citizens, and which enabled them to be fully part of the collective endeavors of a stable and safe community.

This view did not mean everyone could – or should – participate directly in politics. It even acknowledged hierarchies and inequalities, either social or imperial.

It was a trade-off between unfettered individual freedom and social stability that people seemed willing to accept. Most Canadians had long been open to the idea that they should have a say in their own government. But they did not totally embrace the U.S. model.

Many people in the U.S. believed then – and now – that violent action is a legitimate form of political expression, a demonstration of popular opinion, or the revolutionary means to achieve a democratic end.

Big cities, like New York or Philadelphia, were periodically the stage of street riots, some persisting for days and involving hundreds of people.

To Canadians, American institutions appeared unable to protect individual liberties in the face of populism or demagogues. Whenever the voting rights of particular groups were expanded or debated, what followed was political instability, civil unrest and violence.

One such example was the 1854 Bloody Monday rioting in Louisville, Kentucky. On Election Day, Protestant mobs attacked German and Irish neighborhoods, prevented immigrants from voting and set fire to property throughout the city. A congressman was beaten by the crowds. Twenty-two people died and many others were injured.

The key vulnerability in the U.S., as 19th-century Canadians saw it, was its decentralization. They feared the disruption that could result from the constant deferral of authority and law to the popular will at a local level. They also were worried about the stability of a political system whose policies and laws could be overthrown by angry masses at any moment.

In 1864, Thomas Heath Haviland, a politician from Prince Edward Island, lamented this state of affairs: “The despotism now prevailing over our border was greater than even that of Russia. … Liberty in the States was altogether a delusion, a mockery and a snare. No man there could express an opinion unless he agreed with the opinion of the majority.”

A Canadian experiment in democracy

Eventually, the provinces chose to form a strong federal union under the British crown, and Canada became a parliamentary liberal democracy. The head of the Canadian state is the queen, and the head of government is the prime minister, answerable to Parliament. By contrast, the U.S. is a presidential democracy. In this system, the president is simultaneously head of state and head of the government, and is constitutionally independent from the legislative body.

In 1865, during the opening speech of the confederation debates, the man who would become Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, expressed his hopes for the future: “We will enjoy here that which is the great test of constitutional freedom – we will have the rights of the minority respected.”

Another Canadian founding father, Georges-Etienne Cartier, reflected upon the historical significance of creating a Canadian confederation at a time when “the great Federation of the United States of America was broken up and divided against itself.”

He declared that Canadians “had the benefit of being able to contemplate republicanism in action during a period of eighty years, saw its defects, and felt convinced that purely democratic institutions could not be conducive to the peace and prosperity of nations.”![]()

Oana Godeanu-Kenworthy, Associate Teaching Professor of American Studies, Miami University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[Over 150,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]