Invasive, Toxic Hammerhead Worms Found in Rhode Island

By Cynthia Drummond / ecoRI News contributor

|

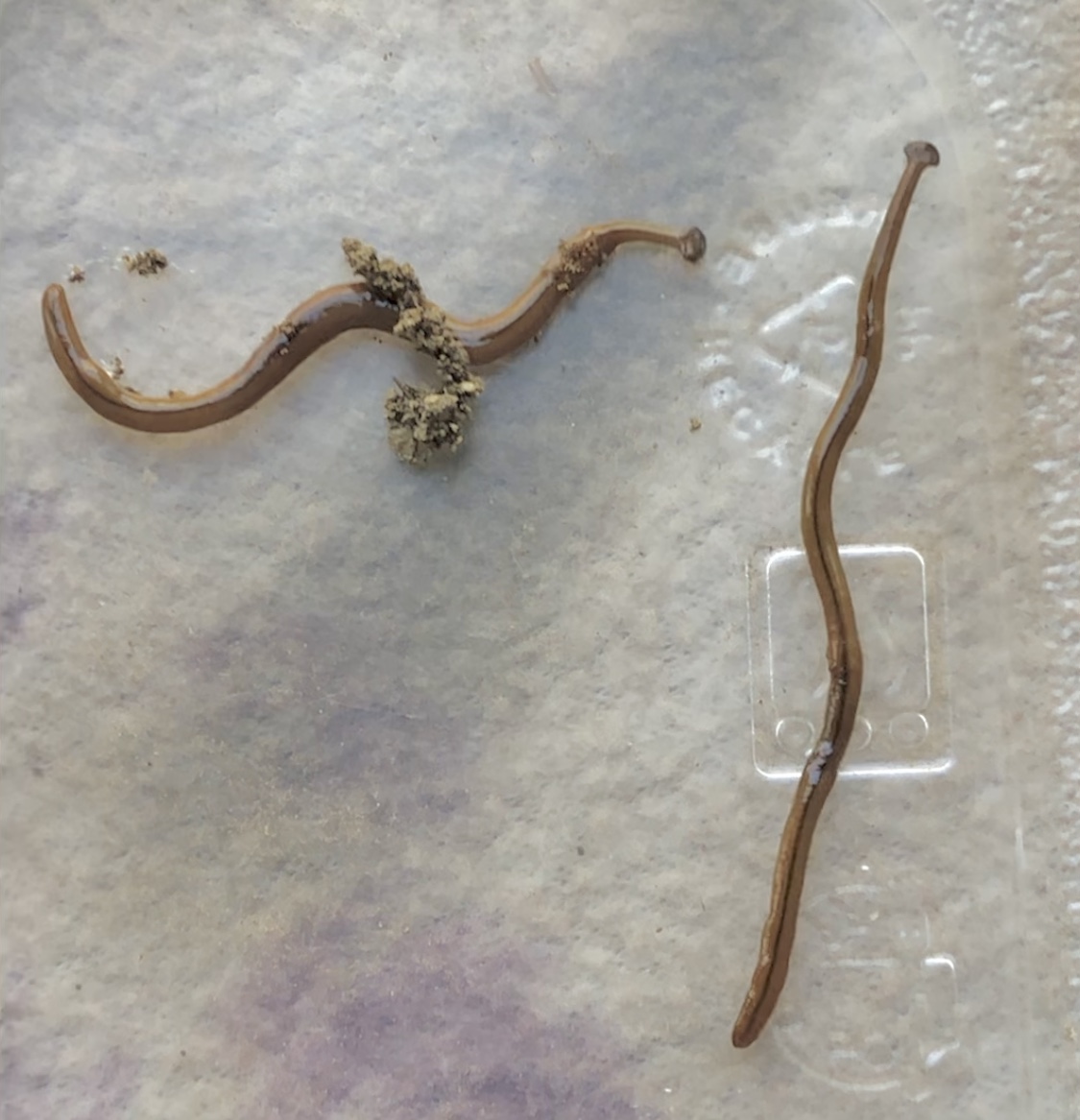

| With their distinctive heads and long, flat bodies, hammerhead worms, which are members of a large family of flatworms, are easy to identify. (Samantha Young) |

HARRISVILLE, R.I. — Samantha Young was working in her father’s garden when she saw some strange-looking worms she hadn’t noticed before. What she had found were invasive hammerhead worms.

“The

three hammerhead worms were all found in my dad’s yard on Round Top [Road] in

Harrisville,” she wrote in an email. “I found them while cleaning up around the

yard. They were all found underneath stuff like buckets, and rocks.”

EDITOR'S NOTE: For those of you unfamiliar with RI geography north of Route 136, Harrisville is part of Burrillville in RI's northwestern corner. - W. Collette

Native

to Asia and Madagascar, the hammerhead worm, or Bipalium Kewense, was

transported to Europe and the United States in shipments of exotic plants. It

has been in the United States since the early 1900s and is most commonly found

in states such as Louisiana, where

conditions are warm and humid. But now, as the climate warms, these invasive

worms are spreading.

With

their distinctive heads and long, flat bodies, hammerhead worms, which are

members of a large family of flatworms, or planaria, are easy to identify. They

are usually striped, and can grow in length to nearly a foot.

The

biggest concern is the damage the carnivorous worms could do to agriculture,

because they are predators of earthworms. While the glaciers killed almost all the native

earthworms north of Pennsylvania, and most of the earthworm species in the

United States were brought here by European settlers, earthworms are important

for soil health.

The

one thing you don’t want to do if you find a hammerhead worm is touch it, or

let your pets, including backyard chickens, eat it.

Hammerhead

worms produce a neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin, which

is also found in puffer fish, which are sometimes served in sushi restaurants

as “fugu sashi,” where they are prepared by only the most highly skilled chefs.

“If

you read some publications out of Texas, they’re kind of saying, ‘Hey you know,

there are really big ones,’ of course, in Texas, they always have bigger things

than anybody else, but they’re saying it may actually be a human health

concern,” Görres said. “Most of that toxin is near the surface of the worm so

you touch it or you play with it, or something like that, it might cause you

harm.”

As

if toxins weren’t enough, hammerhead worms can also transmit harmful parasites

to humans and animals. And they have another unpleasant characteristic: they

regenerate from segments if they are cut up, so chopping them into pieces will

only make more.

Görres

said these invasive worms weren’t considered a threat until they began to

expand their range.

“On

first introduction, there probably weren’t many of them and so now, as they’re

spreading, they’re becoming more obvious to people,” he said. “I, certainly,

over the last five years, have seen a lot more than even 10 years ago.”

Young

said she had to research the three worms she found to identify them.

“I

didn’t know what they were until I googled it,” she said. “I left them in a

Tupperware container until they died.”

If

people can’t handle the worms without protection and they can’t cut them up,

what is the most efficient way to kill them? Görres recommends salting, bagging

and freezing.

“I

read somewhere that in order to kill them, you put them in a bag, you put salt

in there and then you freeze them for 48 hours,” he said. “Double overkill. The

salt will desiccate them and then freezing them, if anything is left, freezing

them will also kill them — 48 hours at minus 20 degrees Celsius, which is what

the freezer is at, usually.”

Since

they are not perceived as a threat to agricultural crops, hammerhead worm

research is not well-funded. Concern has instead focused on another invasive

species from Asia, the snake worm, which

devours the surface material or “duff” of the forest floor.

“They

consume the forest floor, the duff layer and … by the time all that duff layer

is gone, there’s a lot fewer plants in the understory of the forest,” Görres

said.

The

ecological damage caused by hammerhead worms, he said, is minor by comparison,

at least so far.

“I

am not really 100% concerned about them,” he said. “It’s just something I keep

on my radar, because they’ve been reported in the Northeast now for a few years

and I keep finding them in various places, woodlands as well as gardens.”

Görres

also noted dry summers, which are becoming increasingly common in New England,

might limit the spread of hammerhead worms, which need humidity to thrive.

“Things

are getting dryer here,” he said. “They might just be confined to wetlands and

areas where people irrigate.”