Like the flu, COVID mutants and adapts and so must the vaccine

David R. Martinez, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

|

| Viral surveillance and prediction may be key parts of figuring out what goes into a vaccine. Pexels Cover/500px via Getty Images |

I’m an immunologist who studies immunity to viruses. I was a part of the teams that helped develop the Moderna and Johnson & Johnson SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, and the monoclonal antibody therapies from Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca.

I often get asked how frequently, or infrequently, I think people are likely to need COVID-19 booster shots in the future. No one has a crystal ball to see which SARS-CoV-2 variant will come next or how good future variants will be at evading vaccine immunity. But looking to other respiratory viral foes that have troubled humanity for a while can suggest what the future could look like.

Influenza virus provides one example. It’s endemic in humans, meaning it hasn’t disappeared and continues to cause recurrent seasonal waves of infection in the population. Every year officials try to predict the best formulation of a flu shot to reduce the risk of severe disease.

As SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve and is likely to become endemic, it is possible people may need periodic booster shots for the foreseeable future. I suspect scientists will eventually need to update the COVID-19 vaccine to take on newer variants, as they do for flu.

Forecasting flu, based on careful surveillance

Influenza virus surveillance offers a potential model for how SARS-CoV-2 could be tracked over time. Flu viruses have caused several pandemics, including the one in 1918 that killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide. Every year there are seasonal outbreaks of flu, and every year officials encourage the public to get their flu shots.

Each year, health agencies including the World Health Organization’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System make an educated guess based on the flu strains circulating in the Southern Hemisphere about which ones are most likely to circulate in the Northern Hemisphere’s upcoming flu season. Then large-scale vaccine production begins, based on the selected flu strains.

Some flu seasons, the vaccine doesn’t turn out to be a great match with the virus strains that end up circulating most widely. Those years, the shot is not as good at preventing severe illness. While this prediction process is far from perfect, the flu vaccine field has benefited from strong viral surveillance systems and a concerted international effort by public health agencies to prepare.

While the particulars for influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses are different, I think the COVID-19 field should think about adopting similar surveillance systems in the long term. Staying on top of what strains are circulating will help researchers update the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to match up-to-date coronavirus variants.

How SARS-CoV-2 has evolved so far

SARS-CoV-2 faces an evolutionary quandary as it reproduces and spreads from person to person. The virus needs to maintain its ability to get into human cells using its spike protein, while still changing in ways that allow it to evade vaccine immunity. Vaccines are designed to get your body to recognize a particular spike protein, so the more it changes, the higher the chance that the vaccine will be ineffective against the new variant.

Despite these challenges, SARS-CoV-2 and its variants have successfully evolved to be more transmissible and to better evade people’s immune responses. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, a new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern has emerged and dominated transmission in a series of contagion waves every four to seven months. Almost like clockwork, the D614G variant emerged in the spring of 2020 and overtook the original SARS-CoV-2 outbreak strain. In late 2020 and early 2021, the alpha variant emerged and dominated transmission. In mid-2021, the delta variant overtook alpha and then dominated transmission until it was displaced by the omicron variant at the end of 2021.

There’s no reason to think this trend won’t continue. In the coming months, the world may see a dominant descendant of the various omicron subvariants. And it’s certainly possible a new variant will emerge from a nondominant pool of SARS-CoV-2, which is how omicron itself came to be.

Current booster shots are simply additional doses of the vaccines based on the outbreak SARS-CoV-2 virus strain that has long been extinct. The coronavirus variants have changed a lot from the original virus, which doesn’t bode well for continued vaccine efficacy. The idea of tailor-made annual shots – like the flu vaccine – sounds appealing. The problem is that scientists haven’t yet been able to predict what the next SARS-CoV-2 variant will be with any degree of confidence.

|

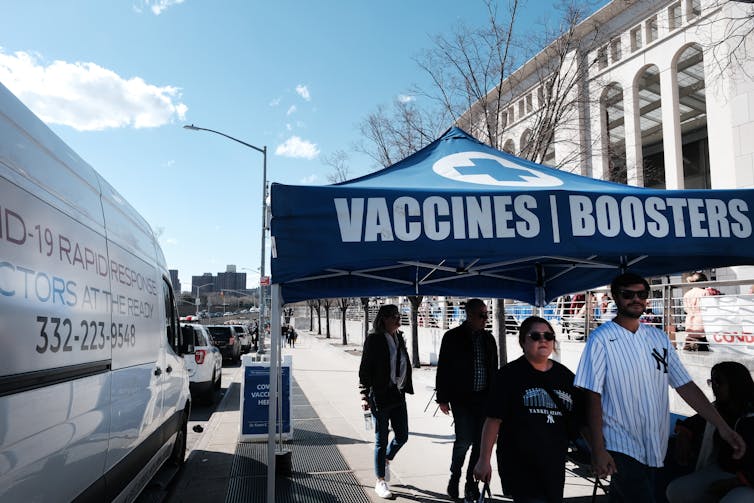

| Periodic booster shots may be in order for the foreseeable future. Spencer Platt/Getty Images |

Planning for the future

Yes, the dominant SARS-CoV-2 variants in the upcoming fall and winter seasons may look different from the omicron subvariants currently circulating. But an updated booster that more closely resembles today’s omicron subvariants, coupled with the immunity people already have from the first vaccines, will likely offer better protection going forward. It might require less frequent boosting – at least as long as omicron sublineages continue to dominate.

The Food and Drug Administration is set to meet in the coming weeks to decide what the fall boosters should be in time for manufacturers to produce the shots. Vaccine makers like Moderna are currently testing their booster candidates in people and evaluating the immune response against newly emerging variants. The test results will likely decide what will be used in anticipation of a fall or winter surge.

Another possibility is to pivot the vaccine booster strategy to include universal coronavirus vaccine approaches that already look promising in animal studies. Researchers are working toward what’s called a universal vaccine which would be effective against multiple strains.

Some focus on chimeric spikes, which fuse parts of the spike of different coronaviruses together in one vaccine, to broaden protective immunity. Others are experimenting with nanoparticle vaccines that get the immune system to focus on the most vulnerable regions within the coronavirus spike.

These strategies have been shown to ward off difficult-to-stop SARS-CoV-2 variants in lab experiments. They also work in animals against the original SARS virus that caused an outbreak in the early 2000s as well as zoonotic coronaviruses from bats that could jump into humans, causing a future SARS-CoV-3 outbreak.

Science has provided multiple safe and effective vaccines that reduce the risk of severe COVID-19. Reformulating booster strategies, either toward universal-based vaccines or updated boosters, can help steer us out of the COVID-19 pandemic.![]()

David R. Martinez, Postdoctoral Fellow in Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.