Defense Department DARPA funds paid for the project

By

Jeff Falk and Jade Boyd

A

research team led by Rice University neuroengineers has created wireless

technology to remotely activate specific brain circuits in fruit flies in under

one second.

In a published demonstration in Nature Materials, researchers from Rice, Duke University, Brown University and Baylor College of Medicine used magnetic signals to activate targeted neurons that controlled the body position of freely moving fruit flies in an enclosure.

“To study the brain or to treat neurological disorders the scientific community is searching for tools that are both incredibly precise, but also minimally invasive,” said study author Jacob Robinson , an associate professor in electrical and computer engineering at Rice and a member of Rice's Neuroengineering Initiative .

“Remote

control of select neural circuits with magnetic fields is somewhat of a holy

grail for neurotechnologies. Our work takes an important step toward that goal

because it increases the speed of remote magnetic control, making it closer to

the natural speed of the brain.”

Robinson said the new technology activates neural circuits about 50 times faster than the best previously demonstrated technology for magnetic stimulation of genetically defined neurons.

“We made progress because the lead author, Charles Sebesta, had the idea of using a new ion channel that was sensitive to the rate of temperature change,” Robinson said. “By bringing together experts in genetic engineering, nanotechnology and electrical engineering we were able to put all the pieces together and prove this idea works. This was really a team effort of world-class scientists we were fortunate enough to work with.”

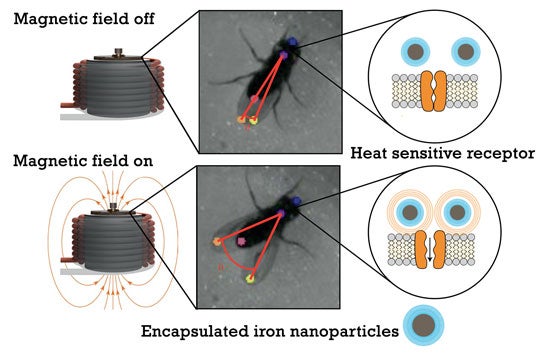

Researchers from Rice University, Duke University, Brown University and Baylor College of Medicine developed a magnetic technology to wirelessly control neural circuits in fruit flies. They used genetic engineering to express heat-sensitive ion channels in neurons that control the behavior and iron nanoparticles to activate the channels.

When researchers activated a magnetic field in the

flies’ enclosure, the nanoparticles converted magnetic energy to heat, firing

the channels and activating the neurons. An overhead camera filmed flies during

experiments, and a visual analysis showed flies with the genetic modifications

assumed the wing-spread posture within approximately half a second of receiving

the magnetic signal. (Figure courtesy of C. Sebesta and J. Robinson/Rice

University)

The researchers used genetic engineering to express a special heat-sensitive ion channel in neurons that cause flies to partially spread their wings, a common mating gesture. The researchers then injected magnetic nanoparticles that could be heated with an applied magnetic field. An overhead camera watched flies as they roamed freely about an enclosure atop an electromagnet.

By changing the

magnet’s field in a specified way, the researchers could heat the nanoparticles

and activate the neurons. An analysis of video from the experiments showed

flies with the genetic modifications assumed the wing-spread posture within

approximately half a second of the magnetic field change.

Robinson

said the ability to activate genetically targeted cells at precise times could

be a powerful tool for studying the brain, treating disease and developing

direct brain-machine communication technology.

Robinson

is principal investigator on MOANA, an ambitious project to develop headset technology for nonsurgical, wireless,

brain-to-brain communication . Short for “magnetic, optical and

acoustic neural access,” MOANA is funded by the Defense Advanced Research

Projects Agency ( DARPA) to develop headset technology that can both

“read,” or decode, neural activity in one person’s visual cortex and “write,”

or encode, that activity in another person’s brain. The magnetogenetic technology

is an example of the latter.

Researchers

from Rice University, Duke University, Brown University and Baylor College of

Medicine genetically engineered neurons that control the posture of fruit flies

to react to signals from a magnetic field. Flies were injected with iron

nanoparticles that converted magnetic signals to heat, activating the neurons.

An overhead camera filmed how flies behaved when neurons were both inactivated

and activated by a magnetic field in their enclosure. (Figure courtesy of C.

Sebesta and J. Robinson/Rice University)

Robinson’s

team is working toward a goal of partially restoring vision to patients who are

blind. By stimulating parts of the brain associated with vision, MOANA

researchers hope to give patients a sense of vision even if their eyes no

longer work.

“The

long-term goal of this work is to create methods for activating specific

regions of the brain in humans for therapeutic purposes without ever having to

perform surgery,” Robinson said. “To get to the natural precision of the brain

we probably need to get a response down to a few hundredths of a second. So

there is still a ways to go.”

The

research was funded by DARPA (N66001-19-C-4020), the National Science

Foundation (1707562), the Welch Foundation (C-1963) and the National Institutes

of Health (R01MH107474).