R.I.’s Affordable Housing Stock Fails to Meet Need

Decades

of implicit and explicit discriminatory housing policies leave Black people

three times more likely than white people to live in neglected and unsafe

housing

By Frank Carini / ecoRI News staff

|

| The amount of affordable housing in Westerly is half of what state law requires. This house, being built in 2020, doesn’t fall into that category. (Frank Carini/ecoRI News) |

Their

eyes welled with tears when they spoke about their current housing situation.

Both women had been through plenty before they were able to call anyplace home.

Karen

(she asked that her last name not be used) welcomed ecoRI News into “my

beautiful home” on Hamilton Street in Providence in early April, about nine

months after she and her three children, 18-year-old twins and a 22-year-old

daughter, moved in.

The

spacious two-story apartment with four bedrooms is a significant upgrade from

the family’s previous housing accommodations. They had moved from a

single-family home they were renting about 3 miles away on Joslin Street

because the landlord neglected the property and ignored their concerns and

requests to have things fixed.

The

house was infested with cockroaches and mice when they moved in, Karen said.

The 46-year-old, who was born and raised in Providence, said her kids stayed at

a friend’s house for a while until “we got the bugs out.” The situation never

improved. She called the owner “a slumlord.”

Before

that, the family of four lived in cramped apartments, at shelters, or with

friends and family, often sleeping on the floor in tight living quarters. The

family had been on waiting lists for affordable housing for years — not ONE

Neighborhood Builders (ONB), the family’s current landlord; they didn’t know

about the Olneyville-based nonprofit until they applied for housing. Karen said

she even knows people who have even been put on a waiting list for the waiting

list.

“I was crossing my fingers when I applied to ONB,” said Karen, who works as a certified nursing assistant in a Rhode Island nursing home. “When they called, I was ecstatic. I had all my paperwork ready. I’m glad I have this.”

Maribel

(not her real name), a domestic violence survivor, moved into a one-bedroom ONB

apartment with her 10-year-old daughter in April. In early May, the 32-year-old

spoke with ecoRI News, through Spanish translator Wendy Sanchez, ONB’s resident

services coordinator, about what her affordable home means to her and her

daughter.

She

said it gave them their lives back, after a difficult journey that included

having no job and no income and spending time in Boston with a cousin.

With

stable, affordable housing, Maribel found work at a print shop in northeastern

Rhode Island, sharing rides with co-workers since she doesn’t own a car.

Founded

in 1988, ONE Neighborhood Builders has

developed close to 600 affordable homes for individuals and families, including

the ones Karen and Maribel call home. Its mission, beyond building affordable

housing, is to engage “neighbors across Greater Providence to cultivate

healthy, vibrant, and safe communities.”

ONB’s

community work focuses on nine Providence neighborhoods — Elmhurst, Federal

Hill, Hartford, Manton, Mount Pleasant, Olneyville, Silver Lake, Smith Hill,

and Valley. The neighborhoods where most of ONB’s apartments are located,

Elmwood and Olneyville, have a Hispanic/Latino population of 67% and 57%,

respectively. Black residents make up 18% and 14% of each neighborhood,

respectively. Overall, the head of ONB households are 76% Hispanic/Latino, 21%

Black, and 18% white, and 63% of the nonprofit’s residents are female.

The

types of rental apartments by income eligibility break down this way for fiscal

2021 (area median income,

or AMI, is the midpoint of a region’s income distribution — half of families in

a region earn more than the median and half earn less than the median):

- Low income 51-60 AMI (46%): A household with an income between 51% and 60% of AMI; $46,740 for a family of three.

- Very low income (44%): A household with an income between 31% and 50% of AMI; $38,950 for a family of three.

- Low income 61-80 AMI (5%): A household with an income between 61% and 80% of AMI; $62,300 for a family of three.

- Extremely low income (5%): A household with an income of less than 30% of AMI; $23,400 for a family of three.

The

neighborhoods in the 02908 and 02909 ZIP codes that ONB serves have

similar demographics and

deal with a host of pressures: about 40% of the people live in poverty; the

homeownership rate is 25%, the regional average is 60%; last year 22% of

kindergarten children in Federal Hill, Olneyville, and Valley had elevated

blood lead levels; and the average life expectancy in the nine communities is

nine years lower than that of the city’s other neighborhoods.

Rising

rents and decades of insufficient building of low-income housing has resulted

in a dearth of affordable apartments in Rhode Island.

When

ecoRI News spoke with Karen, her daughter was searching for an affordable

one-bedroom apartment, with no luck. Karen said the least-expensive units

outside of “the slums” cost $1,200 a month — $14,400 a year — with nothing

included.

“She’s

discouraged. I told her to apply to ONB and keep looking,” Karen said. “You

need to work two to three jobs to afford an apartment.”

What’s affordable

Housing

is considered affordable if a household pays no more than 30% of its annual

gross income on housing-related costs: rent or mortgage, insurance, taxes, and

utilities. Households are considered “cost-burdened” if they pay more than 30%

and “severely cost-burdened” if they pay more than 50% of their income on

housing.

ecoRI

News spoke with Jennifer Hawkins, ONB’s executive director, in May. She said

making homelessness a brief and non-recurring experience in Rhode Island can be

done, but it would require many state leaders and advocates to rethink their

approach. It would also require financial commitments that go beyond a year or

two.

She

noted the state already has adequate infrastructure to provide emergency

shelter. What Rhode Island lacks, she said, is an adequate inventory of affordable

housing and rental vouchers to help low-income individuals and families cover

rent. Instead of overbuilding shelter facilities to temporarily address the

crisis, Rhode Island needs to invest in creating affordable housing to solve

the problem, according to Hawkins.

“Unfortunately, Rhode Island has not, I think, invested in the policy and research arm at the office of Statewide Planning to really do the analysis required to have a nuanced understanding of our housing gap,” said Hawkins, who has two decades of experience in the nonprofit community development and housing sectors, including time in New York City and Boston.

“You have to slice it and dice it

many different ways so you can really put your arms around exactly what we need

and then where we can place it. The urban cities can’t bear alone the

responsibility of producing affordable housing.”

She

noted restrictive zoning rules that don’t allow for density make it difficult

to build affordable housing. She also said the state lacks incentives to help

municipalities create more affordable housing.

“I

think it’s important to recognize that we have underfunded the production of

affordable housing for decades,” Hawkins said. “That’s why we’re in this supply

gap that we’re in.”

The

numbers reveal Rhode Island is trending in the wrong direction when it comes to

addressing housing affordability, according to a 2016 report by HousingWorks

RI at Roger Williams University. For instance, the number of

cost-burdened renters and owners in the state increased by 44% from 2000 to

2012, even as the number of households in the state did not significantly

change. The number of severely cost-burdened households increased 59% during

that time.

In

2000, about one-third of renters were paying unaffordable rents; by 2012 it was

close to half. The numbers were similar for homeowners. In 2000, about

one-quarter were cost-burdened; by 2012, it was more than a third.

The

52-page report explained why Rhode Island needs more affordable housing. The

report projected a need of 34,600 new homes by 2025, most as multifamily

properties because of a growing need for smaller households. It also noted

nearly all new households over the next decade are projected to have incomes

below 120% of the AMI, which was $89,300 for a family of four in fiscal 2015.

It was $103,800 for a family of four in fiscal 2021.

“With

the population aging and birthrates declining, Rhode Island will see a growing

number of single-person households, resulting in a downward trend in average

household size,” according to the 6-year-old report.

Earlier

this year, the National Low Income Housing Coalition released its annual The Gap report,

noting 57% of Rhode Island’s lowest-income renters are severely cost-burdened.

There

are 49,032 extremely low-income households in Rhode Island and a shortage of

24,050 affordable and available rental units — an 11% increase in shortages

compared to 2021, according to The Gap.

However,

much of the housing being built and planned in Rhode Island is opulent

residences, from large, second homes to McMansions to a proposed 46-story

luxury residential tower in Providence. The website touting The Fane Tower says

its “Well-designed luxurious apartments and amenities will attract residents.”

Besides

creating housing that is out of the financial reach of most people, these

lavish estates are also gobbling up finite resources.

To

borrow the title of the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s annual report,

the gap between housing costs and what many Rhode Islanders can afford has been

a persistent — and routinely ignored — problem for sometime. Decades of

underinvestment in affordable housing development has forced the Ocean State’s

lowest-income renters to rent apartments beyond what they can afford.

The Rhode Island Comprehensive

Housing Production and Rehabilitation Act and the Rhode Island Low and Moderate

Income Housing Act require that 10% of a municipality’s housing

stock be affordable. Ten of the state’s 39 municipalities — Central Falls,

Cranston, East Providence, Newport, North Providence, Pawtucket, Providence,

Warwick, West Warwick, and Woonsocket — are exempt because of their percentage

of rental housing and/or current affordable housing inventory.

“Affordable”

units are required to have a subsidy (state or local), with restrictions to

assure they will remain affordable for a minimum of 30 years, according to

the Rhode Island Office of Housing

and Community Development.

In 2014, only one of the 29 required

municipalities reached the 10% threshold — New Shoreham (Block Island) at

10.6%. Seven years later, in 2021, only two municipalities — New

Shoreham (10.5%) and Burrillville (10.3%) — met the mandate, while eight,

including New Shoreham, had lower percentages, albeit nominally, and five

remained the same.

Efforts

are gradually being made to address the situation; they’re just not large

enough in scale to solve the problem.

Last

year, Rhode Island’s Housing Resources Commission approved nearly $31 million

in grants through the Building Homes Rhode Island program to support 23

affordable housing developments. These grants will produce or preserve more than

600 units of affordable housing in 13 municipalities (Burrillville,

Charlestown, Coventry, East Greenwich, East Providence, Hopkinton, Jamestown,

Middletown, Newport, Providence, Tiverton, Warwick, and Woonsocket), according

to a Dec. 1, 2021 press release from

the governor’s office.

Central

Falls recently broke ground on

two adjacent vacant lots, 229 Washington St. and 12 Hood St., that will be

developed into new owner-occupied housing. The sites will become new

four-bedroom single-family homes.

Central

Falls Mayor Maria Rivera has said she wants to develop 200 new affordable

housing units. Currently, 11% of the city’s housing stock is considered

affordable.

Seeing red

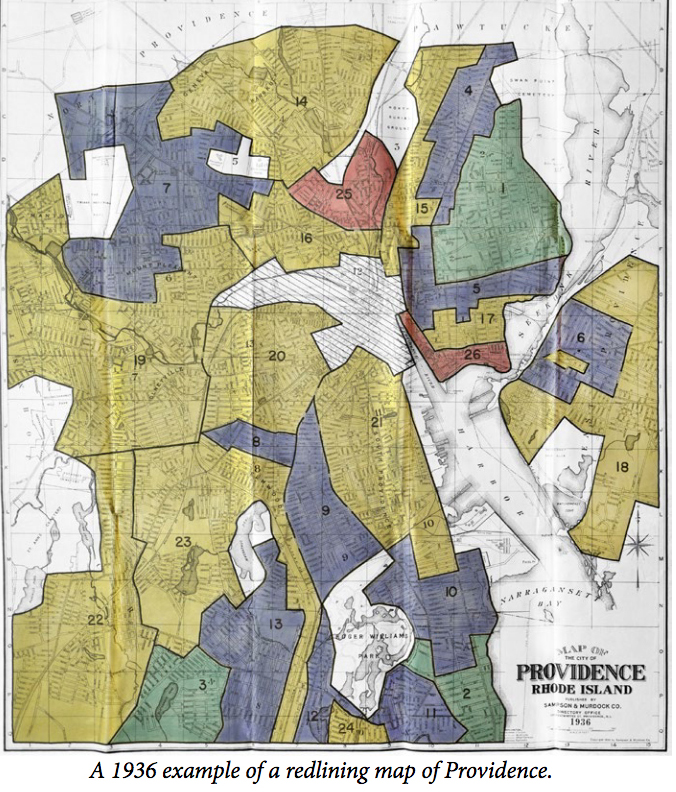

|

| Neighborhoods were color-coded on maps: green for the ‘Best,’ blue for ‘Still Desirable,’ yellow for ‘Definitely Declining,’ and red for ‘Hazardous.’ |

In

the early 20th century, when Black people migrated North to escape the South’s

anti-Black laws, many didn’t have jobs or money and, thus, were forced to live

in substandard housing. In the South, Jim Crow laws reinforced racial

segregation, prohibiting Black people from moving into white neighborhoods.

In

the 1930s through the ’60s, the U.S. government’s redlining policy denied

federally backed mortgages and credit to Black people. It blocked Black people

from obtaining homes, home loans, and home repairs. This practice remains a

major factor in the wealth gap that exists between Black and white families,

according to the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at

Ferries State University.

Between

1935 and 1940, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC)

used redlining to legitimize racial discrimination. The federal agency created

color-coded maps that indicated risk levels for long-term real estate

investment and mortgage security.

Neighborhoods

that received an A, colored green on the maps, were considered the “Best.”

Neighborhoods that received a D, colored red, were considered “Hazardous.”

Metropolitan areas with a large population of Black families were the most

likely to be redlined, while areas that were predominately white were the most

likely to be colored green. In redlined neighborhoods, it was virtually

impossible to get a loan.

As

a result, Black people had limited access to quality homes and all the

advantages that go with living in a safe space: a healthy environment, good

schools, and better food options. The living field still isn’t level.

Six

decades after the U.S. government’s use of redlining ended, Black people are

still three times more likely than white people to live in neglected and unsafe

housing, with poor insulation, outdated appliances, inefficient heating

systems, and lead water pipes and paint.

In

fact, the gap in homeownership rates between white and Black families is larger

today than it was in 1960, before the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, according to the

Department of Justice.

A 2018 study by

the National Community Reinvestment Coalition examined how neighborhoods were

evaluated for lending risk by the HOLC, and compares their recent social and

economic conditions with city-level measures of segregation and economic

inequality. The study revealed:

Underwriting

practices institutionalized by the Federal Housing Administration acted to

further cement residential segregation in the urban structure of the United

States.

Between

1934 and 1962, the Federal Housing Administration and later the Veterans

Administration financed more than $120 billion worth of new housing. Most of

the funding (98%) went to white people, and less than 2% went to Black people

and other people of color, according to George Lipsitz’s 1998 book The Possessive Investment in Whiteness. At

the time, Black people represented about 10% of the population.

The

economic and racial segregation created by redlining persists in many

cities to this day. Redlining buttressed the segregated structure of U.S.

cities. Most of the neighborhoods (74%) that the HOLC graded as high-risk or

hazardous are low-to-moderate income today. Additionally, most of the HOLC

graded hazardous areas (nearly 64%) are people of color neighborhoods now.

Persistent

economic inequality. There is significantly greater economic inequality in

cities where more of the HOLC graded high-risk or hazardous.

Persistent

residential segregation. Both Black and Hispanic residents of

“hypersegregated” cities are unevenly distributed and have lower levels of

interaction with non-Hispanic whites. People of color also tend to be more

clustered in areas of cities where there were more HOLC-labeled high-risk or

hazardous neighborhoods.

While

the federal government may no longer use redlining polices to intentionally

punish specific groups of people, lending discrimination and implicit and

explicit discriminatory housing policies remain a serious problem.

Last

year, to address the now-illegal practice of redlining, the Department of

Justice launched the Combatting Redlining Initiative.

“Redlining,

a practice institutionalized by the federal government during the New Deal era

and implemented then and now by private lenders, has had a lasting negative

impact,” according to the initiative. “For American families, homeownership

remains the principal means of building wealth, and the deprivation of

investment in and access to mortgage lending services for communities of color

have contributed to families of color persistently lagging behind in

homeownership rates and net worth compared to white families.”

In

the 1960s, white homeownership was 65% and Black homeownership was 38%, a

27-point gap, according to a 2019 report by

the Urban Institute. Six decades later that gap is even wider, with white

homeownership at 72% and Black homeownership at 43%, a 29-point gap.

HousingWorks

RI’s 2021 Housing Fact Book noted

the home ownership rate for white households in Rhode Island is 68%, which is

double the rate for Black households and more than double the rate for Latinos.

The

federal government may be cracking down on lending discrimination, but it still

wields its power to oppress marginalized populations. The Internal Revenue

Service audits poor families — households with less than $25,000 in annual

income — at a rate five times higher than it audits everybody else, according

to a fiscal 2021 Syracuse University analysis.

The

current tax code also provides lopsided benefits to homeowners compared to

renters.

The need to get housing right

On

the heels of a research project on public housing, the University of Rhode

Island’s Center for Nonviolence & Peace Studies hosted

a two-day Get Housing RIght Conference this

spring to explore affordable housing options and public policy.

ecoRI

News attended the May 12 online discussion that included Diane Yentel,

president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, and

Dr. Rahul Vanjani, director of the Lifespan Transitions Clinic at Rhode Island

Hospital.

Yentel,

day one’s keynote speaker, began her talk by saying “housing is health care and

always has been.” She noted decades of structural racism in housing led to

inequitable health outcomes for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color.

She said 12 million households are at risk of losing their homes, and there is

a significant nationwide shortage of affordable homes.

“We

need to advance racial equity. The obvious racial disparities in housing didn’t

happen by accident,” said Yentel, noting Black people make up 13% of the

population but 40% of the unhoused. “We have a housing lottery system and only

25 percent get the assistance they need. There are deep structural flaws in our

housing system.”

Vanjani

said the lack of housing is based on racist practices. He noted the health-care

system needs to become more involved in addressing social issues.

“Health-care

providers focus on biomedical needs, but we need to expand that focus,” Vanjani

said. “Contextualizing care needs to be the focus. Invaluable social resources

need to be included in medicine.”

To

create housing justice, Yentel said the country needs to build off the

“historic and unprecedented” moratoriums on evictions put in place during the

height of the coronavirus pandemic. She said the “solutions are pretty simple,

if not easy. Inaction is expensive.” She listed four solutions:

- Make rental assistance universally available.

- Push, preserve, and expand the supply of affordable housing.

- Push for the emergency rental system to be permanent.

- Rebalance the power that tilts toward landlords.

“The

only thing we lack to end homelessness is the political will and the pandemic

proved it. We aligned to protect renters and low-income people,” Yentel said.

“We funded solutions unlike anything in our lifetime. We did the impossible for

those two years — housing justice.”

The

National Low Income Housing Coalition and the Urban Institute are among the

advocates that support shared-equity rental housing as a

solution. Basically, governments or nonprofits buy rental housing with

low-interest loans, tenants continue to pay rent, and surplus cash flow and

appreciation goes to tenants proportionate to the rent they pay.

Several

professors in URI’s Department of Political Science were approached last year

by the South Kingstown Housing Authority and asked to generate research on

public housing in the state, according to Get Housing RIght Conference

organizer Jennifer Vincent, who graduated in May with a master’s degree in public

administration. The South Kingstown Housing Authority is looking to create a

new public housing development in town and wanted to ensure it would be

developed effectively.

The

team of professors and graduate and undergraduate students managed a research

project funded by the Rhode Island Foundation, the South Kingstown Housing

Authority, and the Jonnycake Center. The team conducted about 300 door-to-door

surveys of public housing residents living throughout the state. The surveys

asked residents about their satisfaction with the physical conditions of public

housing, access to amenities such as public transportation, and interactions

with housing authorities.

Among

the key takeaways was this: Public housing residents want to be active

participants in decision making. About 60% of respondents showed interest in

participatory budgeting and fixing up their complex.

A

survey was also sent to administrators and direct service staff at about 100

nonprofits asking one question: What state or municipal policy would you change

to ease access to affordable housing for the people benefiting from your

program?

Some

of the responses:

- More enforcement of the 10% rule even if it requires the state overruling current municipal building codes.

- Zoning laws in all 39 municipalities that support affordable housing efforts.

- Land-use reform is needed. Most of the state is zoned for single-family residential; few municipalities allow multifamily housing.

- Eliminate single-family zoning in towns with more than 20,000 people.

- Rent control.

The

second day of the conference, hosted at the Shepard Building in Providence,

focused solely on affordable housing in Rhode Island and included politicians

and policy experts. The featured panelists included Rep. David Morales,

D-Providence, Rep. June Speakman, D-Warren, Sen. Meghan Kallman, D-Pawtucket,

Brenda Clement of HousingWorks RI, and the URI research team.

With

3.8 million homes short of meeting housing needs, both rental housing and

ownership and double the number from 2012, the nation is in an “extreme state”

of underproduction, according to a recent report from

Up for Growth.

The nonprofit research group, made up of

affordable housing and industry groups, noted that four years ago the nation’s

housing affordability problem appeared to be concentrated along the coasts and

in the Southwest. The crisis has since deepened to impact urban, suburban, and

rural areas and is “profoundly impacting residents in nearly every state,”

according to the 39-page report.

Home

prices are up about 30% over the past few years, and a report published in June

noted that in May the median monthly asking rent in the United States surpassed

$2,000 for the first time. In Providence, the median asking rent in May was

$2,283, up 3.4%, according to the Redfin report.

“More

people are opting to live alone, and rising mortgage-interest rates are forcing

would-be homebuyers to keep renting,” Redfin deputy chief economist Taylor Marr

said. “These are among the demand-side pressures keeping rents sky-high. While

renting has become more expensive, it is now more attractive than buying for

many Americans.”

This

year’s National Low Income Housing Coalition report noted that not a single

state has an adequate supply of affordable rental housing for the lowest-income

renters. In fact, there are just 36 affordable and available rental homes for

every 100 of the lowest-income renter households nationwide.

“We

talk about the problem, but that’s all we seem to do,” said Karen, the ONB

tenant. “We actually need to make housing more accessible. Make it affordable,

but not free, and don’t judge people by their income.”

Editor’s

note: ecoRI News was unable to attend the second day of the “Get Housing RIght

Conference.”

To

view the series, click here.