Remarkable Anti-Aging Drug Delivers Positive Effects on Health and Lifespan With Brief Exposure

By MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR

BIOLOGY OF AGING

Imagine being able to take a medicine that prevents the decline that comes with age and keeps you healthy. Scientists are searching for drugs that have these effects. The current most promising anti-aging drug is Rapamycin.

It is known for its positive effects on life and health span in experimental studies with laboratory animals. It is often given lifelong to obtain the maximum beneficial effects of the drug. However, even at the low doses used in the prevention of age-related decline, negative side effects may occur. Plus, it is always desirable to use the lowest effective dose.

A

research group at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Aging in Cologne,

Germany, has now shown in laboratory animals that brief exposure to rapamycin

has the same positive effects as lifelong treatment. This opens new doors for a

potential application in humans.

Research scientists are increasingly focused on combating the

negative effects of aging. Lifestyle changes can improve the health of older

people, but these alone are not sufficient to prevent the ills of older age.

Repurposing existing medications for ‘geroprotection’ is providing an

additional weapon in the prevention of age-related decline.

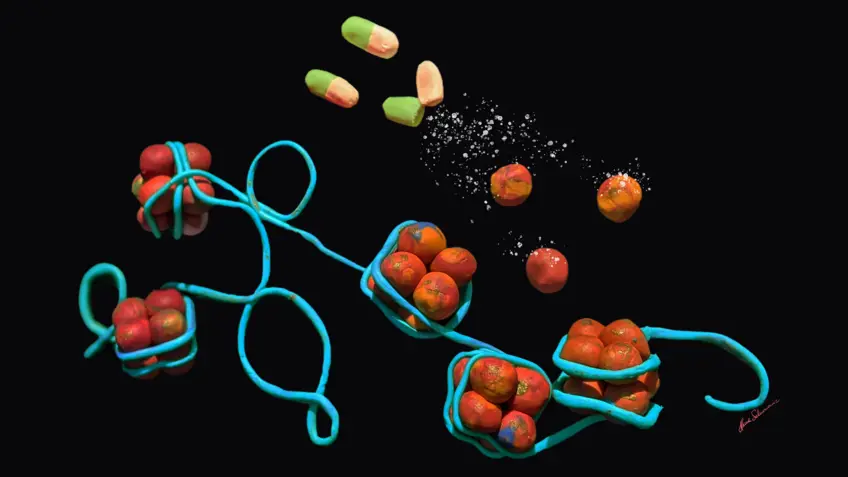

Currently, the most promising anti-aging drug is rapamycin, a cell growth inhibitor and immunosuppressant that is normally used in cancer therapy and after organ transplantations.

“At the doses used clinically, rapamycin can have undesirable side effects, but for the use of the drug in the prevention of age-related decline, these need to be absent or minimal.

Therefore, we wanted

to find out when and how long we need to give rapamycin in order to achieve the

same effects as lifelong treatment,” explains Dr. Paula Juricic. She is the

leading investigator of the study in the department of Prof. Linda Partridge,

director at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Aging.

Only

brief exposure

The scientists have tested different time windows of short-term

drug administration in fruit flies. They found that a brief window of 2 weeks

of rapamycin treatment in young, adult flies protected them against age-related

pathology in the intestine and extended their lives. A corresponding short time

window, of 3 months of treatment starting at 3 months of age in young, adult

mice, had similar beneficial effects on the health of the intestine when they

were middle-aged.

“These brief drug treatments in early adulthood produced just as

strong protection as continuous treatment started at the same time. We also

found that the rapamycin treatment had the strongest and best effects when

given in early life as compared to middle age. When the flies were treated with

rapamycin in late life, on the other hand, it had no effects at all. So, the

rapamycin memory is activated primarily in early adulthood,” explains Dr.

Thomas Leech, co-author of the paper.

One

step closer to applications

“We have found a way to circumvent the need for chronic, long-term

rapamycin intake, so it could be more practical to apply in humans,” says Dr.

Yu-Xuan Lu, also co-author of the paper.

Prof. Linda Partridge, the senior author of the study, comments:

“It will be important to discover whether it is possible to achieve the

geroprotective effects of rapamycin in mice and in humans with treatment

starting later in life, since ideally the period of treatment should be

minimized. It may be possible also to use intermittent dosing. This study has

opened new doors, but also raised many new questions.”

Reference: “Long-lasting geroprotection from brief rapamycin

treatment in early adulthood by persistently increased intestinal autophagy” by

Paula Juricic, Yu-Xuan Lu, Thomas Leech, Lisa F. Drews, Jonathan Paulitz,

Jiongming Lu, Tobias Nespital, Sina Azami, Jennifer C. Regan, Emilie Funk,

Jenny Fröhlich, Sebastian Grönke and Linda Partridge, 29 August 2022, Nature Aging.

DOI: 10.1038/s43587-022-00278-w

The research for this study was conducted at the Max Planck

Institute for Biology of Aging and was funded by the CECAD Cluster of Excellence

for Aging Research.