Brown scholars offer key facts and insights on the persisting public health emergency.

Brown University

Even before the U.S. had emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic, the country’s first case of the monkeypox virus was reported in May 2022. In late July, the World Health Organization declared the ongoing monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency, and in early August, the U.S. government followed suit.

Over

the past few months, the monkeypox outbreak has both offered opportunities to

apply lessons learned from COVID and presented its own unique challenges.

Although the U.S. is currently seeing a decline in cases, the outbreak continues

to affect patients both domestically and abroad.

Scholars

from Brown’s School of Public Health and Warren Alpert Medical School offered

some key facts and insights on this complicated public health issue.

Philip A. Chan

Associate

professor of medicine, associate professor of behavioral and social sciences;

consultant medical director of the Rhode Island Department of Health

Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men are primarily being affected by monkeypox —although anyone can get it.

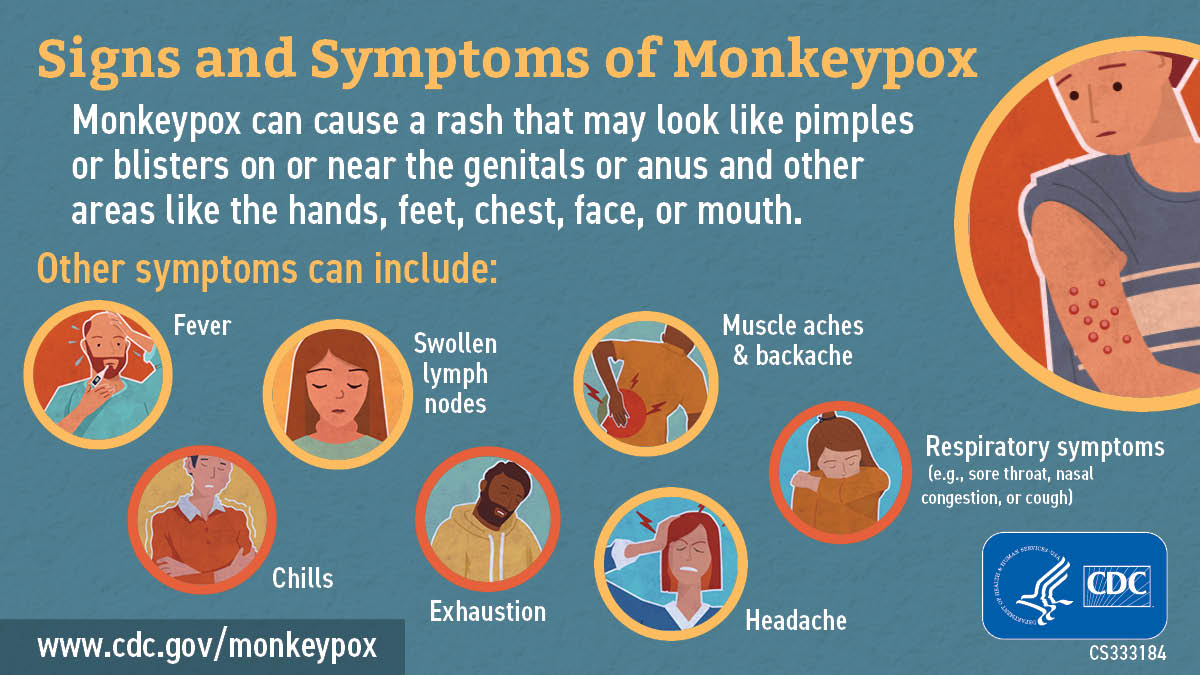

The

virus can spread via direct contact with a person with monkeypox or by touching

objects, fabrics and surfaces that have been used by someone with monkeypox. We

don't know yet whether monkeypox is sexually transmitted, but it is associated

with sex. It was initially believed that monkeypox was spreading by droplets

(similar to SARS-CoV-2), but that type of transmission appears to be much less

common than expected. Monkeypox is much less infectious than COVID-19.

Gay,

bisexual and other men who have sex with men are primarily being affected by

monkeypox — although anyone can get it. It is important for public health to

continue to actively communicate risk to affected populations so they can make

informed decisions about behavioral changes and prevention options, which

include vaccination.

Despite

the death of a person in the U.S. from monkeypox (and

a second possible death in Texas under investigation), it is not believed that

the virus is becoming more lethal. We do know that people who are immunocompromised

(e.g., who are HIV-positive with a low CD4 cell count), who are receiving

chemotherapy, or who have been diagnosed with certain other medical conditions)

are at higher risk of complications from monkeypox. People who are

immunocompromised and diagnosed with monkeypox should seek treatment

immediately.

There

is a need for more federal public health resources to address monkeypox, as

well as COVID-19, avian flu and whatever else happens in the future. Our

country is in urgent need of a framework and a national plan with resources on

how to address these emerging threats to public health.

Joseph

Metmowlee Garland

Associate

professor of medicine, clinician educator; medical director, Infectious

Diseases and Immunology Center, the Miriam Hospital

Unfortunately, you can’t just get a monkeypox vaccine at your local pharmacy like you can the COVID vaccines.

The

monkeypox vaccine is issued from the CDC directly to state health departments,

who determine how to distribute their limited supply to the highest-risk

populations. Unfortunately, you can’t just get a monkeypox vaccine at your

local pharmacy like you can the COVID vaccines.

On

top of that, there’s a shortage, which is the result of several factors. First,

the vaccine is intended for smallpox, so those planning for a stockpile were

not necessarily anticipating a widespread outbreak of monkeypox. Further,

expiring vaccines had not been not replenished and there were delays in

ordering and securing replacement vaccines. The vaccine we are using, Jynneos,

involves two doses; it is only manufactured by one company in Denmark, and they

have a certain capacity. The global spread of this epidemic has put an acute

demand on the vaccine manufacturers from countries around the world, including

many in Europe.

In

order to get the vaccine to more people, providers are following the CDC’s alternative dosing regimen of

administering the vaccine intradermally, or between the skin layers, instead of

subcutaneously, or under the skin. An intradermal vaccine can induce a stronger

immune response because of how many immune cells we have in our skin. The FDA

did a study on the difference between intradermal and subcutaneous

administration of the Jynneos vaccine at the currently used doses and found

that study participants had similar levels of immune response (measured by

antibody levels) with the lower dose intradermal vaccine. That allows us to give

a much lower dose to get the same level of effect: one-fifth of the dose

induces the same level of immune response in studies — that allows for

potentially five times as many people to get the vaccine.

But

there’s a trade-off. In general, this is a harder way to administer a vaccine,

and more people have skin reactions to this method— we’ve seen mild swelling,

redness or discoloration at the injection site. In some people, that can

persist for a long time, which is important to be aware of.

And

it must be said that no vaccine is 100% effective. We don’t have much data on

any vaccines for monkeypox specifically. Jynneos was tested in an animal model

of smallpox (a very similar and related virus), but we still need to see actual

results in a real-world setting. Data show that it takes about six weeks from

the first dose (and two weeks after the second dose) for people to reach full

immunity. Up until that time, people still have a risk of being infected. After

that time, most people should have protective immunity — but again, we still

will need to back that up with real-world data as we accumulate it.

Amy

S. Nunn

Professor

of behavioral and social sciences, professor of medicine; executive director,

Open Door Health

We haven’t encountered much vaccine hesitancy with monkeypox at Open Door Health. Our challenge has been unprecedented demand for a new service.

At

our Open Door Health clinic, we provide primary

care and other preventative and sexual health services for the LGBTQ+

population. We have vaccinated over 700 people to date, and more people are

coming in every day.

We

always ask the people we serve what they want, and how we can do it in the way

that’s best for them — instead of telling them what we think is best for them.

One thing that came up in our community listening tour with gay men was that

people were worried about scarring on their face, body or genitalia, and they

said that concerns about scarring really motivated them to get vaccinated.

People were also afraid of getting sick, or experiencing a great deal of pain

from monkeypox.. People were also afraid of getting sick or experiencing pain

caused by monkeypox.

We

haven’t encountered much vaccine hesitancy with monkeypox at Open Door Health.

Our challenge has been unprecedented demand for a new service.

We

built the infrastructure to do this very fast. When we started, the entire

clinical team worked 80-hour weeks so that we could offer the monkeypox vaccine

to everyone who walked through the clinic’s doors – men who have sex with men,

sex workers and others who might be at risk. Now we’re trying to integrate

monkeypox vaccinations into our primary care work flow. The thing is, there’s

currently no federal funding for this work that we can access. We do it because

it’s important to the people we serve and aligns with the clinic’s mission and

values, but this mission has cost the clinic $200,000 so far in terms of staff,

time, communications – we’ve even had to bump other priorities. There needs to

be a federal financial response to the monkeypox outbreak to help clinics like

ours care for our patients. This problem isn’t unique to us; this is a crisis

for clinics around the country who want to do the right thing.

William

C. Goedel

Assistant

professor of epidemiology

To

keep on top of the monkeypox outbreak, we need to accelerate access to

promising therapeutics.

For most people with monkeypox, treatment generally involves symptom management. But the antiviral drug Tecovirimat (also known as TPOXX) may be able to alleviate severe symptoms. TPOXX is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of smallpox, a virus similar to monkeypox. Health care providers can request TPOXX through their local health department, but they may be unaware of its availability or the process for obtaining it. Because TPOXX was developed to work against smallpox as part of a bioweapons strategy in response to the events of 9/11, TPOXX is only available from the Strategic National Stockpile. In order to prescribe it, providers are required to fill out significant amounts of paperwork. This process creates a barrier to access: The bureaucratic process for obtaining tecovirimat from the CDC is cumbersome and time-consuming for providers.

To

keep on top of the monkeypox outbreak, we need to accelerate access to

promising therapeutics. The development of an emergency use protocol by the CDC

could significantly streamline the process, saving precious time for patients

in need of the medication. In the meantime, it’s essential that

prescribers are trained and educated about this monkeypox treatment — not just

how to use it, but the steps to obtain it from the CDC and the paperwork

involve in that process.

Jennifer

Nuzzo

Professor

of epidemiology; inaugural director of the Pandemic Center at the Brown

University School of Public Health

We

need to learn from this to move forward with this outbreak and future

pandemics… And we need to train future public health leaders to act swiftly in

the face of a new infectious disease threat.

JENNIFER NUZZO Professor of epidemiology; inaugural director of the Pandemic Center at the Brown University School of Public Health

The outbreak of monkeypox in the U.S. was yet another test of our country's capacity to act swiftly and effectively to stop the spread of an emerging pathogen. We were well-positioned to succeed. Public health labs in states throughout the country and at the CDC had the capacity to run tests for the virus when it was first detected. The U.S. had a stockpile of vaccines to stop transmission and experimental treatments to heal patients. However, we were slow to expand use of these tools and to make sure that patients and health care providers could access them easily enough to rapidly stop the virus from becoming entrenched.

We also lacked the ability to rapidly assemble and

analyze data on who was getting monkeypox and to ensure that our efforts to

expand testing, vaccinate and offer treatments were sufficient or whether we

needed to change course. And we struggled to communicate who was likely

most at risk of infection and how they can protect themselves without encouraging

stigmatization of these patients. These missteps allowed the virus to spread

throughout the U.S. and jeopardize prospects for containment.

We

need to learn from this to move forward with this outbreak and future

pandemics. Infectious disease threats — like monkeypox, COVID-19 and the recent

resurgence of polio — are the hazards of our time, and we need to prepare for

them as we would for other recurring hazards, like natural disasters, fires or

hurricanes. We need to build better data systems and a well-coordinated,

responsive testing system that can identify cases early, accurately and

efficiently. And we need to train future public health leaders to act swiftly

in the face of a new infectious disease threat, even when there is uncertainty

about how it may unfold.