URI researchers eradicate malignant tumors in mice

By Kevin Stacey

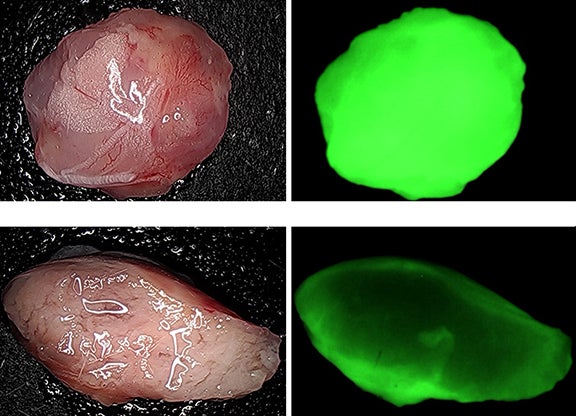

An untreated tumor (top left) is highly acidic, as indicated by its response to fluorescent dye (top right). Just days after treatment (bottom left), the tumor stroma is disrupted and pH decreases (bottom right).

Researchers from the University of Rhode Island and Yale University have demonstrated a promising new approach to delivering immunotherapy agents to fight cancer.

The approach involves tethering an immunotherapy agent

called a STING agonist to an acid-seeking molecule called pHLIP® (pH-low

insertion peptide). The pHLIP molecules target the high acidity of cancerous

tumors, delivering their immunotherapy cargo directly to cells in the tumor

microenvironment. Once delivered, the STING agonists engage the body’s innate

immune response to fight the tumor.

In a study published in Frontiers of Oncology, the team showed that just a single dose of the pHLIP-STING agonist combination eradicated colorectal tumors—even large, advanced tumors—in mice. The treated mice also developed lasting immunity, enabling their immune systems to recognize and fight cancer long after the initial tumors were gone.

While the researchers caution that

results in mice don’t always translate to humans, the findings do lay the

groundwork for a potential clinical trial testing the safety and effectiveness

in cancer patients.

“STING agonists are an important class of immuno-modulators, but research has clearly shown that they often don’t work on their own and need to be targeted in some way,” said Yana Reshetnyak, a physics professor at URI and a senior author of the new research. “What we show here is that using pHLIP to target tumors through their acidity, we can successfully go after a variety of different cell types within the tumor microenvironment and achieve synergistic and quite dramatic therapeutic effects.”

Targeted immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is an emerging approach to fighting

cancer. For cancer to survive and spread, tumors need to hide from the immune

system. In some cases, they do this by expressing proteins that act as immune

cloaking devices—tricking the immune system into thinking tumor cells are

normal, native cells. Immunotherapy aims to disable these cloaking devices.

One way of uncloaking tumors is through use of immune

checkpoint inhibitors, drugs that have proven effective in treating a variety

of cancers. But these drugs don’t work on all tumors. While they work well on

immunologically “hot” tumors with lots of inflammation, they are much less

effective in “cold,” non-inflamed tumors. STING (STimulator of InterferoN Gene)

agonists were developed as a means to turn cold tumors into hot ones—making

them more susceptible to an immune response. They do that by causing cells to

release interferon, a type of red-flag protein that alerts the immune system to

foreign invaders.

The approach has shown promise in the lab, but

administering STING agonist to patients has proven challenging, Reshetnyak

says. The compounds can affect healthy cells, leading to significant side

effects and only modest therapeutic effects.

If there were a way, however, to target STING agonists

specifically to tumor cells—not just cancer cells but also dormant immune cells

within a tumor—it may increase their effectiveness significantly. That’s where

pHLIP comes in.

PHLIP is a peptide (a chain of amino acids) derived

from bacteriorhodopsin, a membrane protein that enables some single-celled

organisms to convert light to energy. Research led by Donald Engelman at Yale

showed that pHLIP has a special affinity for acidic environments.

“When pHLIP encounters a cell membrane with a neutral

pH, it will sit on the surface briefly and then pull away,” said Engelman, who

is a co-author of this new study. “But if it’s in an acidic environment, then

the peptide folds into a helix, crosses the cell membrane and stays there.”

When Reshetnyak joined Engelman’s lab as a

postdoctoral researcher in 2003, she got the idea to try using this helix to

seek out cancer cells. It’s well known that malignant tumor cells tend to be

highly acidic. Along with Engelman and fellow URI physics professor Oleg

Andreev, Reshetnyak has been working for two decades to develop pHLIP as a

cancer-seeking delivery mechanism.

The team has shown that they can tether molecules to

the part of the pHLIP peptide that enters the cell membrane. Those cargo

molecules could be diagnostic agents that help doctors to see tumors more

clearly, toxins that kill cancer cells, or immuno-modulators like the STING

agonist. Because pHLIP only enters cells in highly acidic environments, they

can target tumor cells while leaving healthy cells alone.

There are currently two ongoing clinical trials

testing the safety of pHLIP compounds in cancer patients. And the team

continues to look for new ways of using the peptide. In this new study, the

researchers aimed to find out if pHLIP could successfully target

immunotherapeutic molecules that cause the immune system to attack tumors.

Eradicated tumors

To test whether targeting via pHLIP would increase the

effectiveness of STING agonist activity, the researchers gave 20 mice with

small colorectal tumors (100 cubic millimeters) a single injection of the

pHLIP-STING agonist. Within days, the tumors disappeared entirely in 18 mice.

The team also treated 10 mice with larger tumors (400 to 700 cubic millimeters)

with a single injection. Seven of those mice saw tumor eradication. For

comparison, 10 mice received injections of untargeted STING agonist. Tumors

remained in all mice, despite a modest slowing of growth for a short time.

The treatment also appears to have stimulated immune

memory in the treated mice. When cancer cells were injected in mice that had

been tumor-free for 60 days, new tumors failed to develop in those mice. That

suggests that once the immune system is primed to attack tumor cells, it

continues to do so without additional treatment.

The high rates of tumor eradication are encouraging,

the researchers say, but what’s also encouraging is the fact that the

pHLIP-STING agonist appears to be targeting multiple types of tumor cells.

Tumors contain more than just cancer cells. Many have a stroma, a kind of

coating of non-cancerous cells that forms both a physical and chemical barrier

that protects the tumor from the human immune system. In studying tumor

structure in the hours following pHLIP-STING agonist injection, the researchers

found a marked decrease in stromal cells.

“The stroma was essentially destroyed,” Reshetnyak

said. “The fact that we’re modulating the behavior of the wide variety of cells

in the tumor stroma as well as the cancer cells themselves means that we’re

inducing interferon signaling synergistically in multiple types of cells and

treating the entire tumor. That’s the advantage of using acidity as our target:

We’re able to go after the whole tumor rather than just certain cell types.”

There is more work ahead before a pHLIP-STING agonist treatment can be used in humans, the researchers say, but these preliminary results are promising. And because pHLIP-based treatments are already approved for clinical trials, the team hopes they will be able to move forward quickly.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM073857).

Engelman, Reshetnyak and Andreev are founders of pHLIP, Inc. and own shares in

the company. The University of Rhode Island and Yale have exclusively licensed

technology to pHLIP, Inc., which is commercializing pHLIP technology.